Word Count: 11922 Words, Reading Time: 40 Minutes

I had begun to put my life in proper perspective by October of 1982, when Mike Wing called from the State Board of Pardons and Paroles. He informed me that the Board had received a formal application for a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank. The application was filed by the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Commit-tee, and the Atlanta Jewish Federation, and directed by a Lawyer's Committee chaired by Atlanta immigration lawyer Dale N. Schwartz. He also stated that the Board wanted to study the case with a minimum of outside pressure and publicity. I felt that this was appropriate and stated my own intention of not publicly seeking out-side intervention from such sources as the media.

He also suggested that if the Phagan family had any factual information concerning the case, we could write a letter to the Board.

I had assumed that because six months had passed an application for a posthumous pardon would not be filed.

Actually, the petitioners had been working on the filing of an application for pardon ever since Alonzo Mann had come forward with his testimony. They felt it to be the basis of a full pardon for Leo Frank.

While posthumous pardons had been granted across the country but never in Georgia before, the obvious question still was: what was the point of seeking a pardon for a dead man?

"I am not working for Leo Frank or his family," Dale Schwartz stated publicly. The core of seeking a pardon for Leo Frank, he said, was an attempt to obtain an official repudiation of anti-Semitism and bigotry and to "remove a blot on Georgia history." As such, the petitioners based their case for pardon not on the legality of the trial and conviction of Leo Frank, but on extra-legal concerns.

The pardon effort, an Anti-Defamation League staffer later stated, was not simply a matter of one person, not just the case of Leo Frank.

"I respectfully disagree . . . ," an official wrote the League's National Director Nathan Perlmutter, "that 'from a broad point of view, the Frank pardon is of no consequence.' An innocent Jew was lynched by a mob inflamed by anti-Semitism. It has never happened before or since in the United States." Ironically, however, exonerating Frank would mean "convicting Jim Conley," and possibly be construed as racism. Even before the pardon effort became public, its leaders had been concerned with minimizing potential offense to Blacks.

Another concern of the pardon effort was the repudiation of prejudice generally, against Blacks and Jews. "This is a justice issue," Schwartz said in reference to some Black critics. "The Klan didn't lynch Jews. They lynched Black people. And what we're trying to show is that's not the way to run justice in this country." Responding to a recent Klan demonstration, a local reporter took up the same theme, reflecting the widespread belief that the Leo Frank case was something more than a transaction between a bureaucratic body and a dead factory owner:

The state should answer Klan bigotry with a clear rebuke. It should let the world know that Georgia does not condone terroristic rule by robed riff-raff; it should let all know that we recognize injustice and are willing to undo it, even at so late a date.

The third extra-legal element concerned Georgia's past as it reflected upon the personal identity and regional pride of Georgians. To "do justice" in the Frank case, this argument went, is to make Georgia a better place, morally, and to make Georgians better people. The League, in a memo, compared the Frank case to the Holocaust:

I agree entirely that our constituency—the literate world—knows that Frank was railroaded. Our constituency also knows that the Holocaust was real, but we continue to counteract Holocaust denial. We have also proceeded on the assumption that it was important for the German nation to come to terms with the past and acknowledge the terrible crime committed in days gone by. Likewise some of us here in Atlanta think it is important that the State of Georgia acknowledge its sins in the Frank case, and repent.

"Georgia will not be pardoned by people of good will until Georgia pardons Leo Frank," the Atlanta Black-Jewish Coalition declared. "We must seize this opportunity," the petition for pardon concluded, "for we believe, as we know you do, in following the Biblical injunction: 'Justice! Justice, ye shall pursue!'

" This last concern apparently spurred counter-argument about the historical stature of Georgia's legal community. To say in the 1980s that Leo Frank was innocent, attorney Edgar Neely argued, impugned not just the Georgia system of justice in 1913 but the reputation of its lawyers in general and particularly Frank's counsel. Though apparently otherwise unconnected to the case, Neely submitted a formal brief opposing the pardon, which stated, in part:

I am speaking as an individual, steeped in the law, who wants the law to be upheld and the judicial system of Georgia not ex post facto impugned.

The leaders of the pardon effort responded at length, including the outlining of the "new evidence" of Alonzo Mann, pointing out that it had been unavailable to Frank's lawyers. Mobley Howell, then Chairman of the Board of Pardons and Paroles, is said to have considered Neely's arguments carefully.

There were four legal means of exonerating Leo Frank: a declaration by the governor proclaiming Leo Frank innocent; a resolution by either the House or Senate of Georgia—or both—proclaiming Leo Frank innocent; a complicated procedure of the courts beginning with an extraordinary motion for retrial; a pardon by the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles. And while Governor Joseph Harris, District Attorney Louis Slaton, and the Georgia Senate all expressed sympathy for the effort to exonerate Leo Frank, all also recommended that they obtain a pardon from the Board of Pardons and Paroles. The petitioners began to see that a pardon would, in fact, best fulfill the extra-legal goals of Frank's exoneration, and that it would be considered by the public as definitive. Dale Schwartz commented.

The public has come to understand the pardon process as an exoneration, particularly if it is coupled with a statement as to the innocence of the applicant.

He stated that a gubernatorial proclamation might appear as "one of hundreds of such proclamations and would not have the publicity impact that a pardon would."

The petitioners also came to feel that a court ruling might appear as though the Jewish community had manipulated a friendly judge.

The goal, then, was a pardon from the Board of Pardons and Paroles. As Dale Schwartz told the editor of Israel Today in a 1984 interview, "It was determined that Georgia would perhaps recognize the type of posthumous pardon which did not merely grant 'forgiveness' for a crime committed in the past, but rather would ask the defendant to forgive the state for having wrongfully convicted him."

To the petitioners, such a pardon seemed impossible to deny.

It didn't take a lot of thought for me to realize that this was just the beginning. This time I was personally involved and affected, and this was what I wanted: I didn't want to be left in the dark again about "news breaking" stories of the case. It seemed my quest had actually just begun. I wondered if I was mentally prepared for what was about to happen.

My father suggested I contact the rest of the Phagan family. He, as well as I, knew that some of the Phagans would be quite distraught and angry over the seeking of a posthumous pardon. They had objected in March, when the idea was first broached, and would continue to object until they died.

I did as my father wished. And we were right in our assessment of the family's opinion: they objected. And, as Mike Wing had stated to me, all, including the Phagan family, hoped for minimum publicity.

In December I contacted Mike Wing about the possibility of my father and I appearing before the Board hearings on the Leo Frank case. He referred me to Silas Moore, who would be in charge of handling the case, and again suggested that we write the Board a letter.

On January 9, 1983, I wrote the Board requesting that the Phagan family be permitted to appear at any Parole Board hearing regarding the Leo Frank case.

On January 17, 1983, I received the following letter from Silas Moore:

Dear Ms. Phagan and Mr. Phagan:

Thank you for your letter of January 9, written in behalf of the Phagan family, requesting to be permitted to appear at any Parole Board hearing on the Leo Frank case. We certainly understand your family's interest in this matter.

This past fall the Board received a formal written application for a pardon, and in fact, was requested to do so by Resolution of the Georgia Senate on March 26, 1982, a copy of which is attached.

The pardon application may have been inspired by the 1982 statement of Alonzo Mann. However, the application is not based solely on that information, and certainly the Board will not be limited to considering that alone.

The applicants have been told that the Parole Board plans no hearing to take oral testimony from anyone. We have requested that all information be submitted in writing. If any members of the Phagan family wish to s are with us information or views about the case, we would be glad to receive their written letters or statements. We would be particularly interested in any factual details about the case they may have.

The Board will likely render its decision sometime this year. It has expressed its determination to base its decision on the facts and evidence. It desires to study the case with a minimum of outside pressure and publicity.

If you have any questions, please give me a call. If you wish, I would be glad to talk with you in our offices. We appreciate your interest.

The letter from Mr. Moore confirmed that, again, my father's intuition about the case—namely, that there would be some sort of political involvement with the Board in even deciding whether to consider the application for a posthumous pardon—was correct.

We discussed the letter and the Senate Resolution. We determined that we had to present our views concerning the Resolution, since we felt that the political involvement would possibly put "outside pressure" on the Board.

So, on February 14, 1983, my father and I responded with a letter to the Board:

Dear Mr. Moore and Board Members:

We would like to present our views concerning the Resolution adopted in the Senate on March 26, 1982:

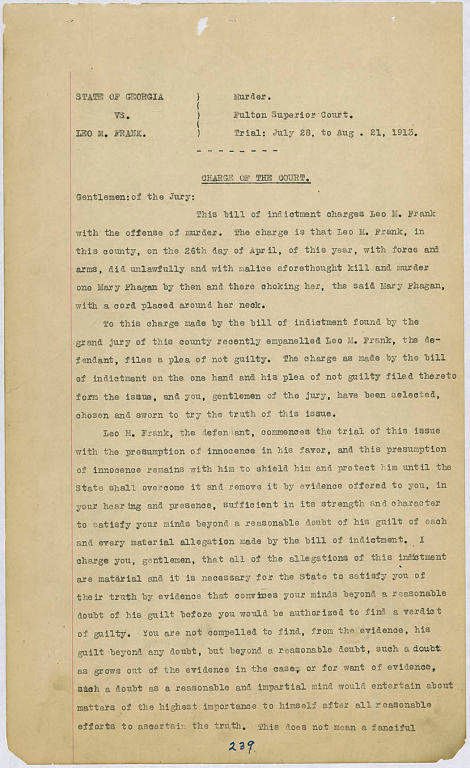

WHEREAS, Leo Frank was tried in the Superior Court of Fulton County in 1913 for the murder of Mary Phagan and

This is a true statement.

WHEREAS he was convicted in an atmosphere charged with prejudice and hysteria; and

This issue was decided by the Supreme Court of the United States. In Georgia Reports, Volume 141, Pages 246 & 247, Numbers 16-18, it states: "The alleged disorder in the courtroom during the progress of the trial was not of such character as to impugn the fairness of the trial or furnish sufficient ground for reversing the judgment refusing a new trial. On conflicting evidence, the judge on the hearing of the motion for new trial, acting as trior, did not err in holding the jurors whose impartiality was attacked were competent."

WHEREAS, he was sentenced to death but his sentence was commuted by Governor John Marshall Slaton; and

Governor Slaton stated: "It will thus be observed that if commutation is granted, the verdict of the jury is not attacked, but the penalty is imposed for murder, which is provided by the State and which the Judge, except for his misconception, would have imposed. Without attacking the jury, or any of the courts, I would be carrying out the will of the Judge himself in making the penalty that which he would have made it and which he desires it shall be made."

WHEREAS, in August of 1915, he was taken by a mob from the state institution in Milledgeville and carried to Cobb County where he was lynched; and

This is true.

WHEREAS, Alonzo Mann, a fourteen-year-old witness at the Frank trial, was threatened with death and was not asked specific questions which could have cleared Frank; and

Frank was ably represented by a counsel of conspicuous ability and experience—Luther Rosser, Reuben Arnold, and Herbert and Leonard Haas. They knew what they were doing.

WHEREAS, Mr. Mann has come forward to clear his conscience before his death and claims that Leo Frank did not commit the murder of Mary Phagan; and

Alonzo Mann gave an opinion that was sworn to, he did not submit any evidence contrary to the conviction of Leo M. Frank. How long did he work at the Pencil Factory? I believe his testimony stated two Saturdays. We challenge and doubt his claim.

WHEREAS, if Leo Frank was not guilty of such crime, it is only fitting and proper that his name be cleared, even after his death. Leo M. Frank was convicted in a court of law by his peers and was duly sentenced to death.

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE SENATE that this body strongly requests that the State Board of Pardons and Paroles conduct an investigation into the Leo Frank case; and, if the evidence indicates that Leo Frank was not guilty, the Board should give serious consideration to granting a pardon to Leo Frank posthumously.

Over the past seventy years, no real new evidence has been submitted. On March 10, 1982, Mr. Mobley Howell stated: "His innocence would have to be completely proven with complete evidence." This case will never be put to rest. Every three to five years, somebody reintroduces the case to the public.

As Phagan family members, we hereby request a copy of the applicant's application and any evidence submitted. We also request any information regarding requests for the Leo M. Frank/Mary Phagan case in the future.

At about the same time my father and I wrote the letter, my father registered as a lobbyist in the Georgia State Capital representing only himself. He wanted to have the privilege of going to the capital and to give a rebuttal to each of the three Senators who had proposed the resolution. In this way the family's feelings could be known.

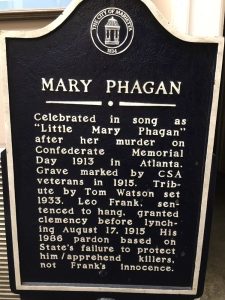

April 26, 1983, was the anniversary of little Mary Phagan's death. I wondered as I prepared for work if anyone else realized it.

As I arrived at work the principal of one of my schools told me there was an article in the Atlanta Journal and Constitution about little Mary Phagan. A pardon has been asked for Leo Frank, he said. For the first time I wasn't angry.

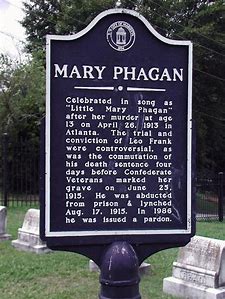

Ron Martz, staff writer for the Atlanta Journal and Constitution reported that the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Committee, and the Atlanta Jewish Federation urged the Board of Pardons and Paroles to vindicate Frank. "The conviction and lynching of Leo Frank was the worst episode of anti-Semitism in the history of the United States, and continues to be a blot on Georgia's criminal system," he'd written. "By issuing a full and complete pardon, the Board of Pardons and Paroles can repudiate the twin evils of prejudice, mob rule, and right an historic wrong." Silas Moore confirmed to the press that the petition for a posthumous pardon was being studied and that this was the first time a posthumous pardon had been considered in Georgia.

Dale Schwartz said that the petition contained three hundred pages of evidence. The major pieces were "an affidavit from Alonzo Mann, who was Frank's office boy at the time of the murder, and a two-and-one-half-hour videotape of Mann giving that affidavit in which he asserts Frank's innocence."

The myth that had grown up around Leo Frank colored popular thinking about him long before Alonzo Mann's testimony became public. "My grandmother would point out where Leo Frank was lynched," Mike Wing was to recall in 1985. "As a child, I grew up thinking an innocent man was lynched. I don't even know if I knew there was a trial."

A recurrent theme of the Leo Frank myth is the alleged confessions of Jim Conley. The pardon application claimed that Conley confessed at least three times: to an insurance agent, in letters to his woman friend, Annie Maud Carter, and to his attorney, William Smith. Schwartz would later say Conley confessed "thousands of times," and argue that these reports "should, standing by themselves, warrant the granting of the posthumous pardon."

Then there was the "secret evidence" supposedly made available to John Slaton in 1915. When Conley's attorney publicly claimed Frank was innocent in 1914, many thought that he had somehow passed secret information on to John Slaton. In his autobiography, I Can Go Home Again Judge Arthur Powell hinted that Frank's innocence would one day be conclusively revealed:

I am one of the few people who know that Leo Frank was innocent of the crime for which he was convicted and lynched. Subsequent to the trial, and after his conviction had been affirmed by the Supreme Court, I learned who killed Mary Phagan, but the information came to me in such a way, though I wish I could do so, I can never reveal it so long as certain persons are alive. We lawyers, when we are admitted to the bar, take an oath never to reveal the communications made to us by our clients; and this includes facts revealed in an attempt to employ the lawyer, though he refuses the employment. If the lawyer were to be so forgetful of his oath as to attempt to tell it in court, the judge would be compelled under the law not to receive the evidence. The law on this subject may or may not be a wise law—there are some who think that it is not—but naturally since it is the law we lawyers and the judges cannot honorably disobey it. Without ever having discussed with Governor Slaton the facts which were revealed to me. I have reason to believe, from a thing contained in the statement he made in connection with the grant of the commutation, that, in some way, these facts came to him and influenced his action. I expect to write out what I know and seal it up; for the day may yet come, after certain deaths occur, when more can be told than I can honorably tell now.

The file to which he refers may have contained a confession obtained by Conley's own counsel. There has been an air of mystery about this evidence in other accounts, as well, such as a recent letter from the late Governor Slaton's nephew to a relative:

He [Governor Slaton] never talked at length about the Frank case, but at that time he and Judge Powell had long since come to the conclusion but elected not to publicize the details. Eventually they decided to destroy the document and stir up no further fuss.

But it was Alonzo Mann's testimony on which the petitioners for the pardon were pinning their hopes. If true, Schwartz eventually argued before the Board, Mann's testimony proved that Jim Conley, the state's chief witness against Frank, had lied on two counts: first, since Mann indicated Mary Phagan was alive as she was carried down, it contradicted Conley's statement that she was dead when he saw her on the second floor; and second, the testimony corroborated Governor Slaton's conclusion in 1915 that Conley could not have used the elevator to carry little Mary Phagan's limp body.

The editorial opinion of the Atlanta Journal and Constitution felt "that the case is compelling and that the Board of Pardons and Paroles should move quickly to clear Leo Frank's name—and the enduring blot on the conscience of Georgia."

The Marietta Daily Journal article by Brent Gilroy stated that the Board of Pardons and Paroles would probably take a year before all the evidence could be digested and a decision be made.

Sherry Frank, Southeast Area Director of the American Jewish Committee, told the Journal that "she had been told the pardon not only would wipe from the books the life sentence given Frank, but also would clear him outright of guilt in Mary Phagan's killing." Stuart Lewengrub, Southeast Regional Director for the Anti-Defamation League, said "We are looking for a complete exoneration." It was also reported that Governor Joe Frank Harris expressed his intention to approve the pardon if it was recommended by the Board of Pardons and Paroles.

When the posthumous pardon effort became public, it attracted its own anti-Semitic response. On September 3, 1983, the New Order of Knights, a fringe Klan group, held a march and rally in Marietta, Georgia, featuring signs reading, "No pardon for the Jew murderer Leo Frank." It was all part of a conspiracy, a group calling itself "Christian Friends of Mary Phagan" wrote to the Pardon Board, "to accuse and hopefully prove, Christians (guilty) of prejudice, bigotry, and 'anti-Semitism' . . . while instilling Christians with feelings of self-hate and self-guilt."

Others felt the way the petitioners did. For the Atlanta Constitution, the "power to right a great wrong" was not the narrow legal case, but the extra-legal ramifications of the Leo Frank case: the ability to signify "that we no longer excuse or forgive prejudice, no matter how old or how recent:

One could argue that this is not the role of a pardons and paroles board, that it is merely expected to rule on narrow issues involving living persons convicted of crimes. Technically, this may be so. But if the power to right a great wrong and do a great good falls into the hands of any citizen—or of five citizens . . . [it is their responsibility] to seize the opportunity and act for the betterment of the state.

Among those who exhorted the Board to pardon Leo Frank were a minister in Tennessee who felt that pardon would "bring a sense of reassurance to many of our citizens who have been hurt and still suffer because of the prejudicial trial to which he was subjected many years ago," and a member of the Christian Council of Metropolitan Atlanta, who viewed a pardon as a way to "repudiate the twin evils of prejudice and mob rule."

I think most of the Phagan family felt as I did about this latest episode: we had known about the application for the posthumous pardon beforehand, and while we weren't pleased with the Board's considering the application, we realized there was more here than just interest in clearing the name of Leo Frank.

What bothered my family most was that little Mary Phagan's horrible murder was not considered. What about her and the effect of her murder on the Phagan family? Little Mary Phagan was the victim and now her surviving family continued having unwarranted publicity. No one seemed to care about that.

Then I took a step to assure that the next generation of Phagan's would not be continually victimized by a news-hungry press. And it was a hard decision. I contacted Ron Martz, who had written the "anniversary" article and informed him of his errors.

Ron Martz, along with most people with whom I come in contact, acted with utmost surprise and shock that I even existed. Chuckling, I told him I did indeed exist, and he should research his facts more thoroughly. He asked if I would consider an article or a series of articles about myself. I told him I was not interested but if I did reconsider, he would be second—as I would let the Tennessean have the first consideration.

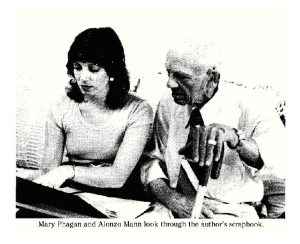

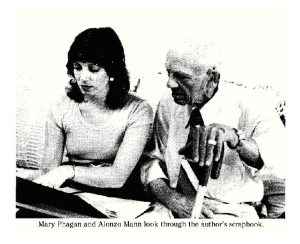

Several months later, I contacted the Tennessean staff and informed them I would like to meet Alonzo Mann and asked if it could be possibly arranged. On July 19 I met Alonzo Mann at my home. He, along with Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne, arrived about 11:00 a.m. I had had second thoughts about whether I was doing the right thing, but I knew when I met Mr. Mann that I was.

to meet Alonzo Mann and asked if it could be possibly arranged. On July 19 I met Alonzo Mann at my home. He, along with Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne, arrived about 11:00 a.m. I had had second thoughts about whether I was doing the right thing, but I knew when I met Mr. Mann that I was.

He was dressed quite dapperly in a gray suit with a light pink shirt, straw hat, and he gingerly carried a cane. Of course, he was quite elderly now, but I could picture him as a young boy working in the pencil factory.

Suddenly I felt a lump of nervousness in my throat. Obviously that same nervousness affected him, for we stood awkwardly in my Livingroom until finally I thrust my hand out and said, "I'm Mary Phagan."

Taking my hand, he said, "I'm Alonzo Mann." I ushered him over to the daybed and we settled back, sitting beside each other, leaning on the fluffy blue pillows.

For about an hour we looked through my huge scrapbook on the murder of Mary Phagan. At one point I read him the article from The Tennessean about his visit to my great-aunt's grave, and although he must have seen the article before, he leaned forward, staring at the clipping, listening intently.

By the time we had finished looking at the scrapbook we had become friends, talking animatedly together, sharing confidences about Mary Phagan's murder, which knit us together although we had never met before.

Finally, having made up a list of things which I wanted to ask him, I began to question him more formally.

"Where were you born?" I asked soberly.

"In Memphis, Tennessee. I had two brothers and one sister, all of whom are dead. My father was a doctor. Instead of paying with money, his patients paid with bacon, eggs, and ham because most of the families could not afford medical expenses," his soft southern accent washed over his words.

My questions came more quickly. "How long did you stay in Atlanta after giving testimony?"

"About a year; then I joined the United States Army."

"Did you ever go to the courthouse besides giving testimony?"

"No. I just passed by."

"Did you ever meet Mary Phagan?"

"I didn't know Mary Phagan, but I knew her by sight."

"Was she as pretty as they say?"

"Yes."

"How long did you work for Mr. Frank?"

"I worked at the pencil factory for several months." (This contradicted my father's understanding that Mr. Mann had only been at the factory for a few weeks.)

"Did you ever keep copies of the original newspapers?"

"No".

"Did you ever confront Jim Conley after what he says he saw?"

"No".

"Did you see Jim Conley murder Mary Phagan?"

"No, but I saw Jim Conley with Mary Phagan in his arms. I believe Jim Conley murdered Mary Phagan, not Leo Frank."

I looked up and suddenly noticed that Mr. Mann appeared tired, his voice had grown less strong.

"Are you all right?" I asked, concerned.

He nodded, "I've had a heart operation recently," he said softly. "I have a pacemaker now."

Shaking my head, I confided, "I have a heart condition also."

"But how old are you?"-1 asked, anxiously.

"Twenty-eight," I replied.

"To have a heart condition at twenty-eight—how difficult that must be," he said sadly.

I nodded. "But it's something you learn to live with."

"Yes," he agreed sympathetically, "accepting life is something we all have to learn."

We began once again to talk of the murder.

He told me that after he encountered Jim Conley, he went home and told his mother what he had witnessed. She told him not to offer any other information if he wasn't asked. When the detectives arrived at his home, they asked him what time he left. That, he said, was their main concern of his account in the matter. He had felt that if he had been asked specific questions, the course of history might have changed.

Then he related a story about little Mary Phagan that to this day I picture in my mind. A bunch of young girls were pushing a red wagon. In the wagon was little Mary Phagan. Her hair was pulled up with big bows. She was beautiful and laughing.

As Mr. Mann recalled the information, I felt for him as I have felt for myself. He, like me, was faced with a struggle. This was his way of resolving it—to come forward and tell the world what he believes he had seen. I wasn't angry at him. I could never be, for I was brought up to respect others' opinions and their values, and with a sense of what one has to do to be true to his own beliefs whatever the difficulty. I empathized with him. Our talk had lasted four hours; we were both exhausted.

As Mr. Mann was preparing to leave, he told me that his main purpose was to get Leo Frank pardoned, and that he had personally asked the Board for a pardon. He asked me to tell the Board again that Leo Frank did deserve a pardon, to come with him.

I felt that I just couldn't.

But something was stirring in the back of my mind. I had automatically accepted the Phagan's' assumption of Leo Frank's guilt—as had my Dad. Here, in Alonzo Mann, was a nice, presumably honest and gentle human being, who strongly believed otherwise.

What was the truth? Would it ever be known?

On July 20, my father received The Thunderbolt, issue No. 290, from the current association of the Ku Klux Klan. Many years before they had asked my father for a "Remember Mary Day," and he had objected. My father did not object then and does not object now to anyone or any organization wishing to pay respects to little Mary Phagan. He objects to individuals or organizations who use little Mary Phagan's death for their own prejudicial purposes.

My father wrote the Anti-Defamation League in Atlanta to find out more about The Thunderbolt. He received the following letter from Stuart Lewengrub:

Dear Mr. Phagan:

Thank you again for letting us know about the approach that was made to you by a representative of The Thunderbolt concerning resurrecting the Leo Frank case. You can be sure that your aunt's memory would have been used solely for a vehicle to promote anti-Semitism.

I have enclosed for your information a copy of The Thunderbolt in order to give you an idea of what this paper and group engages in. For the extreme vulgarity see especially page 10.

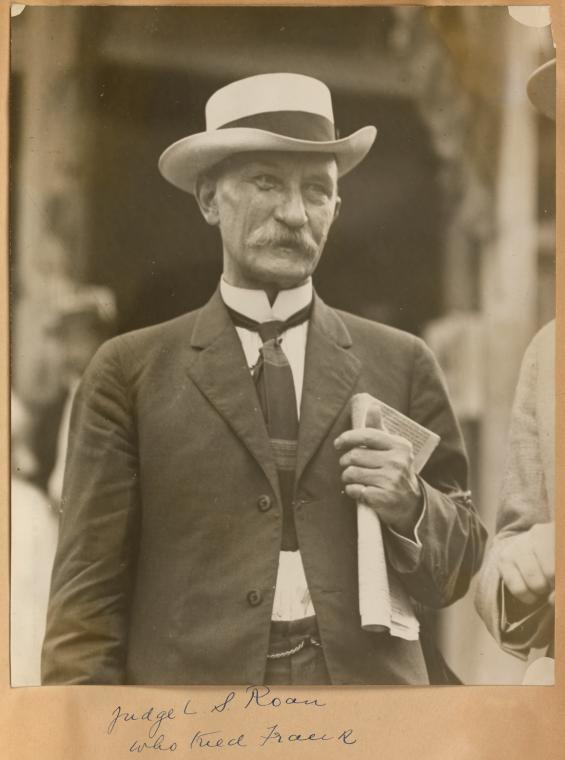

The KKK reprinted in its entirety the statements of Judge Randall Evans, Jr., from the Augusta Chronicle-Herald dated May 15, 1983. In here, Judge Randall Evans, Jr., stated the review of the case and discussed Leo Frank's appeals to the Supreme Court of Georgia: .

. . The Supreme Court consisted of legendary giants—Justice Lumpkin, Justice Beverly Evans, Justice Fish, Justice Atkinson, Justice Hill, and Justice Beck. That court affirmed the conviction, with Justices Fish and Beck dissenting as to the admission of certain evidence; but on motion for rehearing by Frank, the entire court unanimously refused to grant the motion for rehearing.

Frank then filed an extraordinary motion for a new trial before Superior Court Judge Hill, which was overruled, and this decision was unanimously affirmed by the Supreme Court of Georgia.

On June 6, 1914, Frank filed a motion to set aside the verdict, again before Judge Hill, which motion was denied. And all of the justices concurred in the denial, except Justice Fish, who was absent.

So at this point in time the record shows that two impartial judges of Superior Court in Fulton County, twelve impartial jurors in Fulton County, and six impartial justices of the Supreme Court of Georgia, all held that Leo Frank was legally tried, convicted, and sentenced to be hanged.

Bear in mind, this was not in a rural county of Georgia where influential politicians are sometimes thought to sway juries, but it was in the most populous county in the South where it was not shown or even suggested that Jews are the objects of bias. Leo Frank's race was not an issue in the case during the trial.

But the Jewish community of the entire United States sought to shield Frank by saying he was convicted because he was a Jew! Nothing is further from the truth! Money was raised on the streets of New York and elsewhere in the Jewish community for Leo Frank's defense; the best lawyers were employed, including the top defense lawyer in Georgia, Reuben Arnold, associated with and aided by Rosser and Brandon, Herbert Haas and Leonard Haas. But the evidence was overwhelming—and it is still so today. It is interesting to note that Gov. John M. Slaton's term as governor expired on June 21, 1915.

Frank's final date for execution was set for the next day, June 22, 1915. On his last day in office, Governor Slaton commuted Frank's sentence to life imprisonment, thereby thwarting and overturning the due process of law as set forth by the Superior Court of Fulton County and the Supreme Court of Georgia. People were so aroused and dumbfounded by this maneuver they went to the Slaton Mansion. But the Governor called out the National Guard for his protection, and succeeded in escaping. Mobs formed in many other parts of Georgia on learning of the rape of the judicial process by Slaton.

The Jewish community nationwide directed its wrath in large part towards Thomas E. Watson of Thomson, charging that Watson had written incendiary articles in his Jeffersonian, which contributed to Frank's conviction. They urged that Frank was a victim of racial prejudice and bias towards Jews.

Now comes "newly discovered evidence" which is claimed would have proven Frank innocent. Not so! A year ago the new witness, one Alonzo Mann, was first located, and said that as a young man he saw a Negro with the body of Mary Phagan in the basement of the factory building, and that he had remained silent for around seventy years because he was so young at the time, and he just didn't know what to do about it. Our State Department of Archives even wrote in one of its publications that this "new evidence" seemed to prove Frank innocent. I wrote the Department of Archives and pointed out that this was not new evidence at all—that during the trial of the case it was plainly proven that Jim Conley took the body to the basement—and the Archives Department replied with an apology and, in effect, said it had goofed. That correspondence is now a part of our Department of Archives.

The suggestion that a governor or Board of Pardons and Paroles may pardon a deceased person is completely ridiculous.

The Constitution of Georgia provides that "the legislative, judicial, and executive powers shall forever remain separate and distinct." The executive department has no power whatever to reverse, change, or wipe out a decision by the courts, albeit while the prisoner is in life he may be pardoned. But a deceased party can not be a party to legal proceedings (Eubank v. Barber, 115 Ga. App. 217-18). If Leo Frank were still in life, he could apply for pardon, but after death neither he nor any other person may apply for him. As the Supreme Court of Georgia held in Grubb v. Bullock, Governor, 44 Ga. 379: "It [pardon] must be granted the principal upon his application, or be evidenced by ratification of the application by his acceptance of it [the pardon]." Leo Frank's case was finally terminated absolutely against him by the Supreme Court of Georgia on June 6, 1914. He lived thereafter until August 16, 1915, and never did apply for pardon. It is too late now for any consideration to be given a pardon for Leo Frank. Pardon can only be granted to a person in life, not to a dead person. To illustrate the folly of such proceedings, could someone at this late date apply for a divorce on behalf of Leo Frank?

The blood of a little girl cries out from the ground for justice. I pray the sun will never rise to shine upon that day in Georgia when we shall have so blinded ourselves to the records, to the evidence, to the judgments of the court, and the judgment of the people, as to rub out, change, and reverse the judgment of the courts that has stood for seventy years! God forbid!

My father and I were interested in the statements made by Judge Randall Evans. We had been told that the Phagan family were the only ones who had objected to a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank. Evidently there were other people, prominent and well known, who had also objected.

We felt that the judge made some important and relevant points. We felt we had to verify the statements concerning the pardon to find out whether the consideration of the application by the Board was indeed illegal.

I contacted Mike Wing of the Board and asked for a copy of the governing rules in consideration for a pardon. He was again most supportive, and even suggested that we meet. A date was set for August 8, 1983.

When I received the information that I requested, I learned that the application for pardon filed was indeed illegal. Why, then, had it been accepted? There were only two instances in which a pardon could be granted. According to the rules of the Pardons and Paroles Board:

1. A pardon may be granted to a person who, to the Board's satisfaction, proves his innocence of the crime for which he was convicted under Georgia law. Newly available evidence proving the person's complete justification or non-guilt may be the basis for granting a pardon. Application may be submitted in any written form any time after conviction.

2. A pardon which does not imply innocence may be granted to an applicant convicted under Georgia law who has completed his full sentence obligation, including serving any probated sentence and paying any court-ordered payment, and who has thereafter completed five years without any criminal involvement. The five-year waiting period after sentence completion may be waived if the waiting period is shown to be detrimental to the applicant's livelihood by delaying his qualifying for employment in his chosen profession. Application must be made by the ex-offender on a form available from the Board on request.

On July 22 I went to Nashville to meet the whole Tennessean staff, including John Seigenthaler, the president and publisher. Jerry Thompson, Robert Sherborne, and I went to lunch, and on our return a special tour was arranged for me so that I could understand the operation of a newspaper. For the first time I realized the minute details that had to be seen to before an article could be printed.

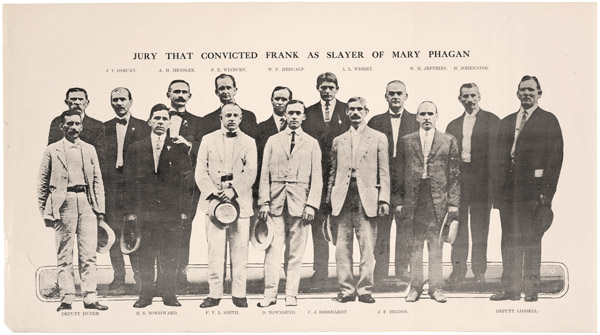

At 3:00 I met with John Seigenthaler, also Frank Ritter, who was Deputy Managing Editor, and Jerry and Robert, as well as Sandra Roberts. On the wall of John Seigenthaler's office was a picture of the jury that convicted Leo Frank. "The picture will remain there until a pardon is granted," Mr. Seigenthaler said.

The staff was very cordial, courteous, and helpful to me. We shared our opinions, both pro and con, and we remained strong in them. Mr. Seigenthaler asked what my father thought about the possibility of a pardon and I told him that he objected unless complete proof of evidence could be submitted. Mr. Seigenthaler felt that no complete proof of evidence would ever come forth, only so-called controversies.

I realized something about myself during our discussion: my opinions were as strong as my father's, and I, too, felt that a posthumous pardon should not be granted unless there was complete proof of evidence. Sherry Frank's statement kept playing in my mind: "The pardon not only would wipe from the books the life sentence given Frank, but also would clear him outright of guilt in Mary Phagan's killing." If the pardon was granted, what would the books say?

Our meeting broke up at 5:30. Mr. Seigenthaler told me that I need not commit to a decision on publicly coming forward and that my name alone was worth something—a special name. He also felt that I was as stubborn in my opinions as he was in his.

He was right: my name was special to me. It would always be. I would never forget who or what or where came from.

Later that evening the staff allowed me to go through Sandra's research files and determine what materials I would like to photocopy. They were extremely responsive and showed no hesitation whatsoever in giving me any of their work.

On the way home I thought about what was happening: I knew that the Board would be deciding soon. And, I thought, the sooner the better; I just didn't think I could go much longer without knowing.

Alonzo Mann called me on July 26 to let me know he had received a letter from a "Phagan" and thought I would be the most appropriate person to have it. He also told me that no matter what decision I made, we would be friends and not have to talk about it. We both realized and understood our mutual struggle to have the truth known. I respected him and he me.

Frank Ritter of the Tennessean called me on July 28 to ask me to let him know when I made a decision about going public. He added that no matter what, he supported me!

The following day Sandra Roberts called to ask if I would agree to a meeting with Bill Gralnick, president of the American Jewish Committee and Miles Alexander, an attorney, on August 3.

During the days that followed, I wondered what the real purpose of the meeting was. I trusted Sandra and liked her. She had become a friend to me. So I knew she would never put me in an uncomfortable position.

The meeting was held at the Kilpatrick and Cody law firm on Peachtree Street. Bill Gralnick and Miles Alexander had concerns about the Phagan family and wanted me to share our views. One of the concerns was what the Phagan family— especially my father's and my—attitudes were toward their organizations.

I told them that we didn't condemn or object to them with regard to their seeking to pardon Leo Frank, but that we did object to a pardon unless complete proof of evidence could be substantiated. We understood their position and hoped they understood ours.

They wanted to know how we would feel if a pardon were granted without such evidence. I told them I knew my father would be mad as hell and that he would seek legal advice if the pardon were granted without adequate proof. My impression was that they felt that Leo Frank did not have a fair trial according to today's standards. They wanted to know how I would deal with the situation if I were Leo Frank's greatniece but I told them I could only deal with the questions and heritage that were mine.

On August 8, 1983, my father and I met with Mike Wing of the Board of Pardons and Paroles. I drove to my parents' home in Decatur, and we agreed the easiest way to get downtown would be via MARTA, the rapid transit system in Atlanta. While we were riding, my father recollected some stories and spoke of childhood memories. As we rode, he described and pointed out where my grandfather lived as a young man and the location of the Fulton Bag Mills where he worked. He explained to me the hard life my grandfather had, but expressed proud feelings for his father. "My father wanted his children to do better than himself, and I feel the same way. I am as proud of you as he was of me," my father squeezed my hand lightly.

We arrived at 2:00 p.m. and registered in the waiting room. Silas Moore greeted us and then introduced us to Mike Wing. Mike Wing was cordial. We freely discussed the idea of a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank. My father did most of the talking. He informed Mike that the Phagan family was opposed to the granting of a posthumous pardon because there was no absolute proof of Leo Frank's innocence. He felt that Alonzo Mann's affidavit offered no proof, but was merely Mr. Mann's opinion that Leo Frank did not commit the murder. The controversies which my father said were "so-called" were exactly that. He felt that they could not be proven and what was essential was the transcript at the Supreme Court of Georgia. And he wanted evidence. Not statements. Not hearsay. Not resolutions. He wanted evidence that would stand up in a court of law. The known facts were brought out during the trial, the jury heard them, and the jury of Frank's peers convicted him. He would fight for Frank's exoneration if new evidence were brought forward, he declared. We would be the first ones to stand up and support that exoneration.

My father's other main point was that those who were seeking the pardon chose to impose today's judicial standards for a trial that occurred in 1913. "How can one compare yesterday with today," he asked. "Today's laws are built on yesterday's court decisions."

"The lynching is a different matter," my father stated. He said "I neither condemn or condone it. Again, we cannot judge yesterday's values based on today's standards of morals." My father told Mike that he was not in any way associated with the Ku Klux Klan but felt that any person or organization could and should have the right to pay little Mary Phagan tribute as long as it wasn't for their own prejudicial purposes. My father then described the "Remember Mary Phagan" incident in 1974 to which he had totally objected.

Mike told us that Judge Randall Evans, Jr., who was quoted in The Thunderbolt, was not a member' of the Klan or had any association with them. He informed us that he was a retired judge and felt that the courts of Georgia should be upheld in dealing with the Leo Frank case. Then he told us about Edgar Neely, the attorney who also opposed the pardon.

My father explained his reasons for wanting to be present when the Board discussed the case. Again, Mike stated that no oral testimony would be taken but that the Board might consider granting us a review. My father felt we had a right to it.

We thanked him for notifying us in advance about the application for a posthumous pardon and for the opportunity of discussing in person our views with regard to it.

On August 9 I contacted Edgar Neely. I wanted to know why he opposed the pardon. He told me that the April 26 article made his blood boil. He personally knew Reuben Arnold and Hugh M. Dorsey and felt it was a disgrace to discredit these fine lawyers. He had even argued cases against Reuben Arnold, and felt he was brilliant. He stated that the evidence is "flimsy because no one is alive to dispute Alonzo Mann," and that he wanted to uphold the courts, "as Leo Frank got a fair trial for that time." Therefore, he had written a letter to the Board stating his opposition.

Sandra Roberts called and asked me how the meeting went with the Board. I told her the Phagan family—including myself—opposed the pardon. I also told her I would make a decision about going public by the end of August.

I was ready for another big step. On August 29, 1983 I decided to acknowledge my name and legacy to the press. I called Sandra and told her. Frank Ritter called back within minutes and we set September 5 for my interview.

On September 1 the Marietta Daily Journal reported: HARRIS: PARDONS, PAROLES BOARD SHOULD RE-CONSIDER FRANK CASE.

The article, by Bill Carbine and Merritt Cowart, was, my family felt, further outside pressure on the Board to determine its decision. Governor Harris was quoted as saying: "From what I've seen and heard, the case deserves reconsideration. From the recent evidence and from what I've heard, I think it is something that the Pardons and Paroles Board could consider." The governor did not say whether he would recommend a posthumous pardon for Frank, as several of the Jewish organizations suggested.

Dr. Edward Fields of Marietta, head of the New Order of Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, maintained the Board could not posthumously pardon anyone in Georgia and based his argument on the opinion of retired Judge Randall Evans, Jr.

Fields scheduled a KKK march for Saturday, September 3, from Marietta Square to Mary Phagan's grave, located off Powder Springs Road. Expectations were that approximately one hundred to one hundred and fifty Klansmen would come to the "Remember Mary Phagan" services. They planned for the Reverend Thom Robb of Harrison, Arkansas, to lead the eulogy, and for a wreath to be placed on Mary Phagan's tombstone.

Marietta Mayor Bob Flournoy announced that a service would be conducted at the First Baptist Church at 148 Church Street in Marietta for all those people opposed to the KKK rally.

September 3 arrived. I stayed home. I felt afraid. A couple of local stations reported the KKK march to Mary's grave. She was eulogized, and a wreath was placed on her tombstone. It was stated that everyone might not agree with what the Klan stood for, but that the remembrance of Mary Phagan is still alive and that this was part of Georgia history. The counter-demonstration at the First Baptist Church in Marietta took place at the same time.

The Atlanta Journal and Constitution and Marietta Daily Journal reported on the Klan march and repeated what the news account reported. It was also reported that the rally and the counter rally were orderly and without interruption. On September 5 the Tennessean staff—Frank Ritter, Sandra Roberts, and Pat Casey (photographer)—arrived at my home. We grilled hot dogs and hamburgers outdoors and ate before we got into the interview. My father did most of the talking.

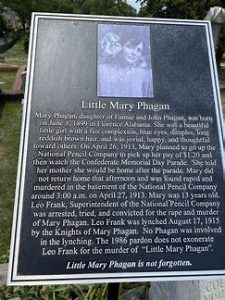

The rest of the family listened attentively, even though we had heard the same stories before. The staff had asked to be taken to little Mary Phagan's grave. It was the first time that my father and I had been there together. When he read the inscription his emotions got the best of him and he cried. His tears made me cry. Her memory bound us together. It was true. Little Mary Phagan was not forgotten.

We felt strongly that the story in the Tennessean, "Little Mary Phagan Is Not Forgotten," would be done honestly, accurately, and with sensitive feelings toward us. We were correct. Frank Ritter called us and read the entire story before it went into print. He wanted to make sure there were no mistakes. We were pleased.

On September 7 Durwood McAlister of the Atlanta Journal wrote an editorial opinion on the Frank case. He felt that the Klan march was a futile attempt on the part of the Klan for its very existence, using the posthumous pardon for Leo Frank as an excuse. His explanation of why the KKK marched to the grave of Mary Phagan was that the legacy had begun there. It was well documented that the modern Klan, known as the "Knights of Mary Phagan"[Vigilance Committee and it was reported that possibly three were part of the lynching] gathered on top of Stone Mountain a few weeks after the lynching of Leo Frank.

It was evident that he believed Leo Frank to be innocent of the murder of little Mary Phagan and that the lynching was wrong.

He felt that Leo Frank should be officially pardoned due to the fact that remaining doubts were dispelled by the confession of Alonzo Mann.

He also stated, "Ten years after the murder, a journalist working for the Atlanta Constitution uncovered new evidence proving Frank's innocence, but prominent Atlanta Jews, fearing the story would only bring on new repercussions, persuaded the newspaper to withhold the publication." I couldn't believe what he was saying. Why didn't he present the evidence to the Board along with Alonzo Mann's eyewitness testimony? I called to try and find out, but my call was never returned. I thought it was incredibly one-sided to present the story in such a way.

My father and I contacted Ron Martz of the Journal to tell him we were ready to public in Georgia. On September 14 the Atlanta Journal printed a letter from Randall Evans, Jr., in response to Durwood McAlister's editorial opinion. It said that Judge Randall Evans, Jr., was not a member of the Ku Klux Klan, but one of the thousands of Georgians who vigorously opposed a pardon for Leo Frank. And it reminded readers that the law of Georgia gave no authority for pardoning a dead man.

Judge Evans responded to every one of Durwood McAlister's statements. His last paragraph also expressed my sentiments exactly: "It is hoped that the Board will permit oral argument on this question and then your hired editorial writers will be privileged to speak out in public and justify their statements written from the privacy of your editorial offices. And perhaps others of us will be allowed to reply."

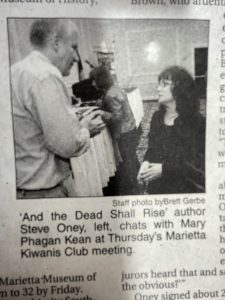

Ron Martz's story, which appeared in the Atlanta Journal on September 22, 1983, provided a step forward for my family—and closed any way of going back. The story titled, "MARY PHAGAN'S LEGACY: Victim's name-sake opposed pardon for convicted Frank," ensured the awareness in Georgia of my family's existence and our opposition to a pardon for Leo Frank unless new proof of evidence was found.

Once again, my father and I were pleased with Ron Martz's reporting.

On September 27, 1983 they permitted my father and me to address the Board. Sitting on the Board were Mob-ley Howell, Chairman, Mamie Reese, member, James Morris, member, Michael Wing, member, and Wayne Snow, Jr., member. They had not realized that the Phagan family existed until Mike Wing informed them. They had become concerned about our feelings and felt that we could share them with the whole Board. They were responsive and understanding.

My father addressed the Board:

My name is James Phagan, and this is my daughter, Mary Phagan, named for little Mary Phagan. We are direct descendants of little Mary Phagan. My father, William Joshua Phagan, Jr., was little Mary's brother. We have come here today to express our views and opinions on the request for a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank, who was the convicted murderer of little Mary Phagan. We prefer to remain within ourselves and not to seek publicity concerning our legacy. We have never said anything before because we never had anything to say. We granted Ron Martz, staff writer for the Atlanta Journal, an interview because of the many articles, editorial opinions, both in the news-paper and on TV stations, and "outside pressure" of the Senate. It was time for it to be known that we do indeed exist, and we are concerned about the granting of a posthumous pardon.

I am here today with my daughter, Mary, to inform you that if you find evidence—not statements, not hearsay, not resolutions, but evidence—that will stand in a court of law to prove the innocence of Leo Frank for the murder of little Mary Phagan, then we would like to come forward with you and tell the world. A miscarriage of justice is a miscarriage of justice whether it happened two years ago or seventy years ago.

We cannot compare yesterday with today's standards. We were not there and it is unfair to say that Leo Frank did not get a fair trial according to today's standards.

The lynching of Leo Frank is an entirely different matter. But I am not going to condemn or condone what was done. You had to be there to understand the feeling that Governor Slaton's commutation order caused. The people felt robbed of justice and became a vigilante committee.

I am emotional about this, and my daughter is emotional about this. We thank you for the opportunity to address you and for letting us express our views and opinions.

I listened to my Dad as he spoke and felt proud to be his daughter and to be a Phagan.

Mobley Howell asked if any of the members had any questions. There were none. Mr. Howell told us the nicest part of this tragedy was that the Board had the opportunity to meet my father and me.

"Young lady," he said, "you are beautiful and have a startling resemblance to your great-aunt."

I smiled and thanked him. He also told us that the Board would render its decision by the end of 1983.

The rendering of this decision weighed heavily on my mind in the following months. During that time, The New York Times, Washington Post and U.S. Magazine sent reporters to interview my father and me. One of the reporters told me outright that my grandfather and father "have been lying" and that Leo Frank was innocent.

My nightmares returned.

In December the Atlanta Journal and Atlanta Constitution reported that the Board of Pardons and Paroles would announce its decision sometime during the last two weeks of 1983. Finally, I thought, it would be over. Or would it? On December 22, 1983 my father went to the State Capital Building, where the Board was to announce its decision. I had left Atlanta that morning for Michigan to spend Christmas with Bernard's family. I wouldn't be there. I would be the last to know. It was frustrating.

When we arrived at Bernard's parents' home, Bernard's mother couldn't wait to tell me: Dan Rather had reported on CBS news that the request for a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank had been denied!

I cried. I was relieved, angry, and sorrowful. I wanted to know if it was truly over.

The Board had begun work on the pardon in January 1983, pretty much going over the same routes of investigation that John Slaton had sixty-eight years earlier.

It organized an investigation staff under the direction of Chairman Silas Moore. This staff was presented with "evidence": newspaper accounts, the trial brief, books, and letters—along with short summaries. Many of the Board members turned to history books to get a perspective on the lynchings, yellow journalism, and the general temper of the time when little Mary Phagan had been murdered.

Alonzo Mann's testimony was the first to be evaluated. While many, including Mr. Mann, felt that his new recollection "proved" Frank's innocence, the Board felt it merely cast doubt on Jim Conley's testimony. It proved in the Board's estimate that Jim Conley lied about carrying Mary Phagan in the elevator, and possibly about her dying on the metal room floor, but it did not prove that Frank had not killed her upstairs nor even that he might not have later killed her downstairs. The Board felt Mann made Conley into a liar, which everyone knew, but not necessarily a killer. Also, the seventy-year gap that made his testimony so sensational to the media and would-be movie producers cast doubt on the validity of his recollections. Moreover, it was perceived that his testimony itself had internal contradictions.

Once the Mann evidence had been weighed and found to be non-conclusive, there wasn't much to go on. "We set about to do almost the impossible," one Board member was to state publicly, "to reconstruct something that occurred seventy years ago—frankly, all the actors were deceased except Alonzo Mann. We were totally at the mercy of accounts by others—mostly journalism accounts, letters—and mostly opinions." He was correct: no other witnesses appeared; no one unearthed heretofore secret material; and, despite rumors, there was no concrete evidence of a confession by Jim Conley. Seventy years after it all began, the Leo Frank case remained a mystery—and, because of the passage of time, an even deeper mystery. Even if Alonzo Mann's account were entirely true, Frank still could have killed Mary Phagan, either accidentally or deliberately, either in combination with Jim Conley or on his own—or he could have been completely innocent.

And there is a third possibility. Someone, whose identity we may never know, could have slipped unnoticed into the pencil factory that day, or have been allowed in by a person on duty. What would this person's motive for killing little Mary Phagan have been? Robbery? A grudge against the pencil company? Anger at Mary because she may have rejected advances this person might have made to her?

I wondered: how many others had thought of this possibility?

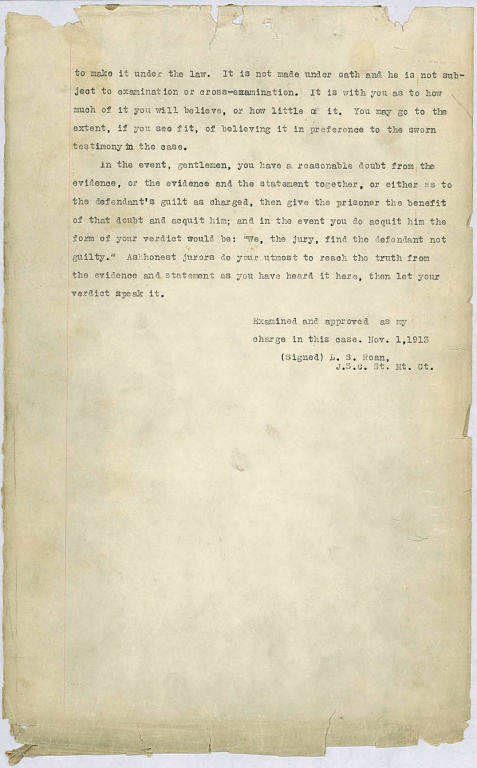

In the announced decision itself, the Board declared cogently:

The lynching of Leo Frank and the fact that no one was brought to justice for that crime is a stain upon the State of Georgia which granting a posthumous pardon cannot remove.

I called my Dad and asked him if it was over. He told me it wasn't. He said that when the Board of Pardons and Paroles changed chairmanship there would be another request filed. Somehow I knew he was right. The Board sent me the decision in response to the application for posthumous pardon for Leo M. Frank. It stated:

On August 25, 1913, Leo M. Frank was found guilty in Fulton County Superior Court of the murder of Mary Phagan. Frank was sentenced to death by hanging.

For almost two years the case was appealed unsuccessfully up to the highest levels in the state and federal court system.

On June 21, 1915, Governor John M. Slaton commuted the sentence of death to life imprisonment.

On August 17, 1915, a group of men took Leo M. Frank by force from the state prison at Milledgeville, transported him to Cobb County, Georgia, and there lynched him.

On January 4, 1983, this Board received an application from the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, the American Jewish Committee, and the Atlanta Jewish Federation, Inc., requesting the granting of a full pardon exonerating Leo M. Frank of guilt of the offense of murder.

In accepting the application, the Board informed the applicants that the only grounds upon which the Board would grant a full pardon exonerating Leo M. Frank of the murder for which he was convicted would be conclusive evidence proving beyond any doubt that Frank was innocent. The burden of furnishing such proof would be upon the applicants.

The information which has been submitted to the Board in this matter is considerable. The pardon application, prompted by the affidavit of Alonzo Mann dated March 4, 1982, is accompanied by numerous other documents submitted in support of the pardon.

Alonzo Mann made statements to journalists Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne, which appeared in a copyright article in the Tennessean on Sunday, March 7, 1982, and made similar statements in Atlanta, Georgia, on November 10, 1983, which were video-taped and recorded by a court reporter in the presence of representatives of the Parole Board. Mann's major point was that, upon re-entering the front door of the National Pencil Company building on April 26, 1913, shortly after noon, he saw the limp form of a young girl in the arms of Jim Conley on the first floor. Upon seeing Mann, Conley is alleged to have turned and reached out toward him with one hand, stating "If you ever mention this, I will kill you." Mann then ran out the front door, caught a streetcar, and went straight home.

Assuming the statements made by Mr. Mann as to what he saw that day are true, they only prove conclusively that the elevator was not used to transport the body of Mary Phagan to the basement. Governor Slaton concluded as a result of his investigation, that the elevator was not used and so stated in his order of commutation. Therefore, this in and of itself adds no new evidence to the case.

Briefs have been submitted in opposition to the pardon. These briefs cite evidence and information to support that view, none of which is new. Numbers of other letters have been received reflecting opinions in support of and in opposition to the pardon.

In addition to the information and material submitted to the Board by interested parties, the brief of trial evidence was obtained from the Supreme Court of Georgia. This extensive document contains all the testimony given at the trial. It is the foundation upon which most arguments on both sides of the issue are based.

The lynching of Leo Frank and the fact that no one was brought to justice for that crime is a stain upon the State of Georgia which granting a posthumous pardon cannot remove.

Seventy years have passed since the crime was committed, and this alone makes it almost impossible to reconstruct the events of the day. Even though records of the trial are well preserved, no principals or witnesses, with the exception of Alonzo Mann, are still living. This case is tainted due to the lynching of Leo Frank. Would he eventually have won a new trial? Would he have been paroled? These questions can never be answered. After an exhaustive review and many hours of deliberation, it is impossible to decide conclusively the guilt or innocence of Leo M. Frank. There are many inconsistencies in the accounts of what happened.

For the Board to grant such a pardon, the innocence of the subject must be shown conclusively. In the Board's opinion, this has not been shown. Therefore, the Board hereby denies the application for a posthumous pardon for Leo M. Frank.

For the Board,

Mobley Howell, Chairman

Though the testimony they had collected convinced the petitioners of Leo Frank's innocence, it must have seemed far less certain to Board members. Dale Schwartz had declared Alonzo Mann's testimony "so credible you couldn't get an actor to do that," but the Board members apparently doubted its value as concrete evidence. To the Board it became clear that Mann's testimony did no more than support Slaton's conclusion, based on the argument of the excrement in the elevator shaft, that Jim Conley did not tell the truth about using the elevator to carry Mary Phagan's body to the basement. But at worst, considering that it took seventy years for Alonzo Mann to come forward, as well as a couple of unsupported assertions in his testimony, the testimony proved nothing at all.

Even if Jim Conley had lied, the Board argued, it did not mean that Frank was innocent. As Mike Wing is quoted as saying in an Esquire article in 1985:

The testimony of Mann sounded good. It matched up with the shit in the shaft to suggest that Conley was the killer. But does his testimony provide sufficient reason to overturn the findings of the court. I wouldn't convict someone seventy years after the fact solely on the testimony of an eighty year old man, so how can I pardon someone on that testimony. To get that pardon, they needed to prove that Frank was innocent beyond a shadow of a doubt, and Mann's testimony just didn't do that.

And, while the pardon effort was motivated by extra-legal goals, it spoke of the pardon process as within the structure of the "judicial process" that provided for "the privilege of pardon and commutation as a 'safety valve' for use in extraordinary cases," and probably worked against it. As if meant for a formal court, the application cited federal court cases to justify "standing" to seek a pardon. The petitioners, in attempting to repudiate anti-Semitism, represented their attempt as a legal effort to repudiate the libel against the Atlanta Jewish Community—an "injury in fact."

The conclusion of the pardon application read:

The public good will be served; a historic injustice will be corrected; a seventy year libel against the Jewish Community of Georgia will finally be set aside, and the soul of Leo Frank will, at last, rest in peace.

The "proof" in Mann's testimony and the collective weight of the number of people, including John Slaton, who believed in Frank's innocence in 1915, provided the claim for Frank's innocence. But the leaders of the pardon effort tied the extralegal justifications for the pardon and their procedural mindset very tightly together, which led to claims of innocence that were not easily justified.

Dale Schwartz publicly responded to the passage in the Board's statement which said that Frank's innocence was not "proved beyond any doubt," with "The 'beyond any doubt standard' is one which none of us have [sic] ever seen applied in Anglo-American jurisprudence." Yet the pardon application itself stated that: ". . . the statement of facts demonstrates, Leo Frank was innocent to a mathematical certainty."

The response to the Board's denial of pardon was immediate and vociferous. The Atlanta Constitution ran an editorial cartoon showing three men, labelled as Board members, packing away a crate. The cartoon was captioned: "Well, that's done . . . Now where can we stash it?" Television and radio broadcasters took up the cry, as did the three groups who had filed for the posthumous pardon—the AntiDefamation League, the American Jewish Committee, and the Atlanta Jewish Federation. They were, they said, in shock. Board members, convinced of the sincerity of their investigation and decision, also pro-claimed themselves in shock. Hundreds of letters criticizing the decision came into the Board weekly.

I felt that the Board made a fair decision. From the start the Board had explained to the applicants that complete and new evidence must be shown before a posthumous pardon could be granted. Alonzo Mann's testimony was not new evidence: in essence it suggested that Jim Conley probably lied about the use of the elevator, but it did not prove that Leo Frank did not murder little Mary Phagan. I wondered if the editors of the papers sifted through the mounds of evidence and whether they had read the 454-page trial transcript or the daily accounts in newspapers. I was amazed that the Atlanta Journal stated on December 23, 1983: "A network news anchor told his viewers last night that Georgia had refused to clear the name of Leo Frank. That's not quite true. Leo Frank's name has, in all but the most formal sense, been cleared for decades. His innocence is understood and accepted by all but those few whose hearts are clouded by connection to Mary Phagan or blackened by remnants of the kind of bigotry that killed him."

I felt they were wrong. There are many people in Georgia, not related to little Mary Phagan and not bigoted, who believe Leo Frank to be guilty. In fact, I have met some people of the Jewish faith who believe Frank to be guilty.

My father requested time on one of our local TV stations to make a rebuttal to an editorial opinion on the pardon. He was denied it. My father decided not to report the TV station to the Federal Communications Commission. This phase was over—for the rest of the world. Not for my family. The story of little Mary Phagan would go on. The denial of the posthumous pardon was, I felt, merely a breathing space.

And the nightmares continued.

Burned down on October 22, 2005.

Burned down on October 22, 2005.

to meet Alonzo Mann and asked if it could be possibly arranged. On July 19 I met Alonzo Mann at my home. He, along with Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne, arrived about 11:00 a.m. I had had second thoughts about whether I was doing the right thing, but I knew when I met Mr. Mann that I was.

to meet Alonzo Mann and asked if it could be possibly arranged. On July 19 I met Alonzo Mann at my home. He, along with Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne, arrived about 11:00 a.m. I had had second thoughts about whether I was doing the right thing, but I knew when I met Mr. Mann that I was.