Last Updated on January 1, 2024 by Mary P.

Leo Frank's removal from Fulton Tower to the Milledgeville Prison Farm was carried out with the utmost secrecy and efficiency.

A car pulled up in front of the main doors of the prison and kept its motor running. Reporters kept watch over it; they could not get information in any other way: the telephone lines into the prison had been disconnected. Meanwhile, Frank was removed from his cell, taken to the basement, and from there to a back alley where another car waited. That car took Frank and the sheriff and deputies escorting him to Atlanta's main railroad station, where they caught a train to Macon. They arrived in Macon at approximately 3:00 a.m. and drove the remaining twenty-five miles or so to Milledgeville.

Frank had lost a substantial amount of weight during his two years in Fulton Tower, and the general dankness there had undermined his health. At Milledgeville, he was put to work in the fields, and his health, along with his spirits, improved.

The warden at Milledgeville, James T. Smith, informed newsmen that he did not need the assistance of troops: he would be able to defend his prison against attack.

Within two weeks of Frank's arrival at Milledgeville, Georgia newspapers gave prominent coverage to the unveiling of Mary Phagan's monument.

Shortly afterwards, the Vigilance Committee met near her grave. They vowed to avenge little Mary's death. A few days later, there were rumors of a plan to kidnap and lynch Leo Frank. Governor Harris put the state police on alert. The plan was, for the moment, thwarted.

Compared to the previous two years, life in Milledgeville was comfortable for Leo Frank. His daily chores, which took place outside, usually took up only four or five hours; the rest of the day he spent in voluminous correspondence. Among those with whom he corresponded was Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, and to him, as to others, Frank expressed his expectation that "right and justice would hold complete sway," and that he would be completely exonerated.

The idyll didn't last. On the night of July 17, approximately four weeks after Frank's sentence had been commuted to life, William Creen, a twice-convicted murderer, slashed Frank's throat with a butcher knife, nearly severing the jugular vein. Frank probably would have died, had not Warden Smith summoned J. W. McNaughton, a physician who was also serving a life sentence at Milledgeville. Creen told the authorities he meant to kill Frank because he wanted to keep the other inmates safe from mob violence, that Frank's presence was a disgrace to the prison, and that he felt he would be pardoned if he killed Frank.

Frank hovered near death for about two weeks. Two letters, one to his mother on August 4, and one to his brother, written the day before, give some idea of Leo Frank's state of mind:

Dear Mother: Just a few words to let you know that I am improving daily and that my dear Lucille is well and on the job. We let the night nurse go, and the day nurse will take her place, dear Lucille holding the fort in the daytime. I hope you did not yesterday or today hear the rumor I heard — viz: that I was dead. I want to firmly and decisively deny that rumor. I am alive by a big majority. You know by my yesterday's letter that the head surgical brace story is also another fabrication. I had a short nice letter today from Simon Wolf. He has taken a great interest in me since I am here. With much love to you and all the folks, I am devotedly your son, Dear Lucille ins me in fond greetings to all.

Dear Chas: Lucille got the package OK and I thank you for the cigars. Lucille wants to know the price of the whole wheat crackers as they will be paid for by the man for whom they were bought. I trust that this finds you and all at home well. Dear Lucille is OK and I am continually progressing to the goal of health. The wound continues to heal rapidly. Tomorrow, we let one of the nurses go and by the end of the week, the other will be unnecessary. My appetite continues fine. We get the fresh Elberta peaches and watermelons here, grown on the Farm. The apples are stewed for me, I also sleep well. It is now just a matter of fully regaining my strength. I sit up in bed, but it will be some time before I can walk about. You know I lost a large quantity of blood which must be regenerated and made up. The piece that I understand was in the Constitution about my having my head in a surgical brace is a lie out of the whole . . . In fact, I haven't now even adhesive plaster on my neck or head. Just a bandage of gauze about my neck (Please phone about this to Herbert Haas). I can move my head reasonable well now, and in time will have use of neck as before. The wound will heal up well and leave only a reasonable scar which will not show much. I look forward to seeing you the end of the week. Lucille joins me in much love to you and all the folks. Devotedly your brother Leo M. Frank

The incident put the carefully laid plans of the Vigilance Committee to abduct Frank on hold.

Also, during August, Tom Watson thoroughly and completely "reviewed" the governor's commutation order in Watson's Magazine. Watson's words undoubtedly further inflamed the feelings against the order—and against Slaton himself. Watson said:

It was the snob governor of high society, gilded club life, and palatial environment that proved to be the rotten pippin in our barrel. With splendid integrity our whole legal system withstood the attacks of Big Money until at length nothing was left but the perfidy of a governor who, in the interest of his client, betrayed a high office and great people. Our grand old Empire has been raped. We have been violated, and we are ashamed . . . The Great Seal of State was gone, like a thief in the night, to do 216 The Murder of Little Mary Phagan for an unscrupulous law firm, a deed of darkness which dared not bask in the light of the sun.

Watson reminded the public that Slaton had been a partner in Luther Rosser's law firm since May 1913, and that the governor had had a secret midnight conference with Rosser before he issued his order: "The noble Rosser went up a back street in his automobile late at night, stopped it a block or two away from the Governor's; and footed it through the alley," he wrote, "like an impecunious person who desired to purloin the portable property of an unsuspecting fellow creature.

"Rosser went into the home of Slaton, and remained for hours, and until after midnight."

According to Henry Bowden, [1945 Study Paper on Leo Frank] everyday citizens were more than willing to act as informers in the case. Telephone operators, switchboard girls, elevator operators, telegraph clerks, and many others kept the phones to Dorsey's home and office busy with little facts they picked up through their jobs. One morning at 6:00 a.m. Dorsey found a streetcar motorman sitting on his doorstep with full information as to the time that Luther Rosser arrived it Governor Slaton's home the night before he issued his commutation order, how long he stayed, and who was with him.

Watson stated that Governor Slaton did not cross-examine Leo Frank or Jim Conley. Watson argued the following points, quoting from the official record at some times in his arguments and at others giving his own views:

THE UNMASHED EXCREMENT IN THE ELEVATOR SHAFT There were only two ways of getting into the basement, the elevator and a ladder. The ladder rested on the dirt floor and it ran up to a hole which was covered by a trap door. The hole was two feet square and witnesses said that it was difficult for one person to pass through the hole and descend the ladder.

Governor Slaton went to the factory and travelled up and down the elevator. He claimed that the body of Mary Phagan could not have been transported to the basement because there was excrement in the elevator shaft which was unmashed.

The bottom of the shaft was uneven so the elevator could rest upon the dirt on one part and not touch it at others; elevators at that time did not always stop exactly at the bottom.

NO BED-TICK IN THE PENCIL FACTORY Even though Governor Slaton argued there was no use for cloth or sacks at a pencil factory, Herbert Schiff, Assistant Superintendent and sworn for the defendant, indicated in his evidence that "empty sacks are usually moved a few hours after they are taken off the cotton."

HAIR ON SECOND FLOOR

Barrett discovered hair on the handle of his bench lathe early Monday morning and the hair was almost immediately recognized as Mary Phagan's, as there was only one other girl who had hair like Mary's, Magnolia Kennedy. Magnolia Kennedy had not been in the factory after Friday and she testified that the hair "was not hers and looked like Mary's."

Governor Slaton gave the public the understanding that Dr. Harris destroyed the value of that part of the State's case.

Ten days after her death, the grave of Mary Phagan was opened and hair was taken from her head. Gheesling, the undertaker, in preparation of the body, cleansed her hair by washing it with tar soap.

Dr. Harris did make a microscopic examination of the hair — one found on the handle of the bench lathe and the other from Mary Phagan's exhumed body. He said: "Affiant further says that the two specimens were so much alike that it was impossible for him to form any definite and absolute opinion as to whether they were from the head of the same person or not." His examination failed to reveal any decided difference in color, size, and texture between the two stands. The conclusion had to be made that it was Mary's hair because the defense could not prove it to be anybody else's.

BLOOD ON SECOND FLOOR Mell Stanford, who had worked for Frank for two years, testified that he swept up the whole floor in the Metal Room on Friday, April 25th. "I moved every-thing, and swept everything; I swept under Mary's and Barrett's machines. On Monday thereafter, I found a spot that had some white haskoline over it, on the second floor, near the dressing room, that wasn't there Friday when I swept. The spot looked to me like it was blood, with dark spots scattered around." Herbert Schiff, Assistant Superintendent and sworn for the defendant, testified that he had seen the spots as well as other witnesses.

Governor Slaton admitted that the white sub-stance, haskoline, was found spread over the splotches.

CONLEY'S AFFIDAVITS

Conley was reluctant to betray his boss, a white man, and denied all knowledge of the crime. He admitted that he did not tell the truth when he finally confessed, he asked to be taken to see Frank. Frank refused to face Conley because his lawyer was out of town.

BLOOD ON MARY'S DRAWERS

The Testimony set forth by Doctors Harris and Hurt said that there was blood caked in Mary Phagan's thick hair; she had blood on her drawers, and blood on her vagina. Evidence indicated some sort of violence and penetration in the vagina which appeared to have been made prior to death.

Governor Slaton's contention was that the blood stains came from her "monthly sickness." Mary Phagan was not filthy in her personal hygiene habits and there was no evidence such as a "bandage" which would have indicated that she had "monthly sickness."

ANNIE MAUD CARTER NOTES William Burns, the celebrated private detective, obtained an affidavit from Annie Maud Carter in which she claimed that Jim Conley wrote her notes. She later refuted her affidavit and both Conley and Carter swore that "their letters had been changed and that the unprintable filth put in them had been forged."

WHERE THE NOTES WERE WRITTEN

Not only did Philip Chambers swear that the order blanks were "in the office next to Frank's office" but Herbert Schiff, the Assistant Superintendent and sworn for the defendant, testified that the paper the notes were written on "can be found all over the plant," not just in the basement.

MONTEEN STOVER'S TESTIMONY, THE TIME QUESTION

Frank was accurate in fixing the time his stenographer left "about 12:00 or a little after" and of the time of Mary Phagan's arrival "between 12:05 and 12:10, maybe 12:07." Frank did not know that Mon-teen Stover had come to his office and claimed that he was in his office "every minute." In his attempt to excuse his absence when Monteen Stover came to his office he stated that he might have "inadvertently left to answer a call of nature."

Governor Slaton argued that Frank must have been in the second office while Monteen Stover waited five minutes for him even though she swore that she looked for Frank in both the outer and inner offices and that "the door to the metal room was closed." Where was Mary, that "Monteen Stover could not see her, when Monteen was in the office, from 12:05 to 12:10?

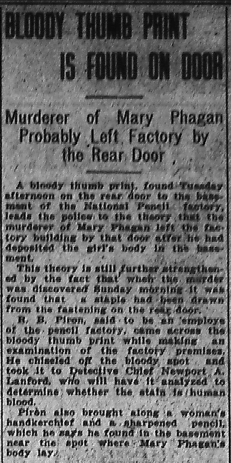

BLOODY FINGERPRINTS ON DOOR

Why did Frank's lawyers not require Jim Conley, the State's star witness, to make an imprint of his fingers?

May 20, 1913: P. A. Flak, a fingerprint expert from New York, visited the Mary Phagan crime scene with Solicitor Hugh Dorsey. Later, Flak took fingerprints from both Newt Lee and Leo Frank.

Tuesday, April 29th, 1913

Murderer of Mary Phagan Probably Left Factory by the Rear Door

A bloody thumb print, found Tuesday afternoon on the rear door to the basement of the National Pencil factory, leads the police to the theory that the murderer of Mary Phagan left the factory building by that door after he had deposited the girl’s body in the basement.

This theory is still further strengthened by the fact that when the murder was discovered Sunday morning it was found that a staple had been drawn from the fastening on the rear door.

R. B. Piron, said to be an employe [sic] of the pencil factory, came across the bloody thumb print while making an examination of the factory premises. He chiseled off the bloody spot and took it to Detective Chief Newport A. Lanford, who will have it analyzed to determine whether the stain is human blood.

Piron also brought along a woman’s handkerchief and a sharpened pencil, which he says he found in the basement near the spot where Mary Phagan’s body lay.

Governor Slaton said that Judge Roan requested a commutation. This statement is false, Judge Roan continued to say, notably to his pastor and daughter, that the evidence unquestionably demonstrated Frank's guilt; and not until Judge Roan had been dead more than two months was a *forged letter presented which stultified Judge Roan's record, and contradicted his judicial declarations of record in this case. [*See Chapter 6 for letters]

DOUBTS OF THE JUDGES

The twenty-three grand jurors, four of whom were Jews, thought Frank guilty, the twelve trial jurors thought so, Judge Roan at least thought the jury was satisfied in its opinion, for he refused to disturb the verdict, and none of the four appellate judges had expressed doubt, simply dissents, as to legal procedure. The Prison Commissioner was not satisfied with the sentence.

Watson's frenzied views on the facts and conjectures about the case further fanned the fears, prejudices, and anger of those in Atlanta, especially the working class, who felt so strongly about the tragedy of Mary Phagan's death.

In a July editorial of the Jeffersonian, Tom Watson mentioned the name, Vigilance Committee and in each subsequent issue of the newspaper, declared the great "Invisible Power" of the Vigilance Committee.

He wrote that lynch mobs were a necessary tool in a democracy and were acceptable as "guardians of liberty." In the August 12, 1915, issue he wrote, "The next Jew who does what Frank did is going to get the same thing we give Negro rapists."

By then a group of about two dozen men from the Vigilance Committee had been selected to reactivate the mission to abduct Leo Frank. Each was a husband and father, a wage-earner, and a church-goer. They all bore well-known Cobb County names. There were no heavy drinkers, no hotheads, no braggarts, and they were mostly older men. Each took a vow never in his lifetime to reveal the name of any participant.

There was an *individual who knew all the vigilante group members names and has told them to me. [Bill Kinney known authority of Leo Frank lynching dies February 21, 2016]

No Phagan was involved in the lynching.

*According to Bill Kinney: in the fall of 1972, he had gotten a call from Judge Manning to come to his home. Judge Manning was a lifelong friend. After dinner, he started off the conversation by saying: 'I've had two heart attacks and soon I am going to die. I want to relate to you a confession given to me by the last of the lynchers of Leo M. Frank. Judge Manning said: 'I have agonized for months whether to pass this information along, or let it die.'

Judge Manning said the person, the youngest of the lynchers, had come to his office after recovering from a severe heart attack. Judge Manning quoted the man as crying: 'Judge, I'm going to hell for helping lynch Leo Frank. I need to get it off my conscious.' The lyncher related his story of the lynching to Judge Manning.

Manning told the old man that there was no corroborating evidence. All the lynchers except him were dead, along with the lawyers and witnesses. 'Go home', Judge Manning told him, and' live with your conscious and don't hurt anyone else. The lyncher dies shortly afterwards as did Judge Manning in 1974.'

May 5, 2004, Flagpole publishes Steve Oney's List of the Leo Frank Lynchers

The mission was prepared like a military operation. An experienced electrician was selected to cut the prison wires; auto mechanics were selected to keep the cars running. The group also included a locksmith, a telephone man, a medic, a hangman, a lay preacher: each was chosen for a reason.

The route the abductors would take had been travelled, measured, and timed. Alternate routes were selected and a timetable set. D-Day was August 16, 1915. The weather was perfect.

Lucille Frank had visited her husband the day before, Sunday, August 15. She started back to Atlanta the morning of the 16. That afternoon the eight cars of the lynch party left Marietta one by one—inconspicuously. They arrived at the prison shortly before midnight on the 16th. They first cut the phone wires. Then they split into four groups: One went to the garage and emptied the gas out of all the cars. One forced themselves into the home of Warden Smith and handcuffed him. "We have come for Leo Frank," they said. "You will find him tomorrow on Mary Phagan's grave. You can come with us, if you want."

"Damned if I go any place with you," Smith answered. Another group went to Superintendent Burke's house and handcuffed him, and then forced him to lead them to the administrative office, where they overpowered the guard.

The fourth group rushed to Frank's cell to awaken him, shackle his hands behind him, and remove him to the back seat of one of the cars.

Within the prison, only the leader of the abductors spoke, and he did so briefly. The men who entered the prison said not a word and neither did the frightened Frank, clad in a monogrammed nightshirt.

It all took eighteen minutes. Frank's captors had a blueprint of the prison, and where his cell was located as well as where guard stations, phones, and electric wires were. No effort was made to resist the group that whisked Frank away. Actually, many guards were sympathetic to the abductors.

Everything went as planned except for two incidents. The man assigned to guard the warden was left behind. There was a delay while some abductors returned to the warden's residence to bring out their companion.

The other incident involved the failure to cut a long distance line to Augusta. This line was used to alert sheriffs in county seats along the possible routes to Marietta. From several of these places, the local sheriff replied: "The parties have just passed through on their way north in automobiles."

The motorcade on the seven-hour, one hundred fifty-mile trip travelled through small towns and back roads as they returned to Marietta via Roswell Road. Forty-nine years before, General William T. Sherman had gone that way from Marietta on his march to the sea.

Along the way, the group experienced tire trouble as the rough roads took their toll. One car had to be abandoned, but the others were repaired. By then the group was aware that they had missed a telephone wire—and that officials probably knew what they were up to.

The original plan was to hang Frank either from a tree in the Marietta City Cemetery, where Mary Phagan was buried, or in the Marietta Square. But dawn was breaking when the group reached Marietta's outskirts. Too much time had been lost, and knowing they would be seen, they wen+ to a more remote side of town.

Frank, frightened but apparently reconciled to his fate, said little. When asked if he wished to confess to the murder of Mary Phagan before being hanged, he is re-ported to have said "I think more of my wife and mother than I do of my life."

"Mr. Frank, we are going to do what the law said to do, hand you by the neck until you are dead," the leader said to Frank, asking if he had any last request. Frank asked that his gold wedding band be removed and re-turned to his widow.

In the grove hidden from Roswell Road at Frey's Gin Mill (where developer Roy Varner's Professional Building now stands), they prepared Leo Frank to be hanged. A piece of brown khaki cloth was tied around Frank's waist, since he had been taken from prison wearing only a nightshirt. A white handkerchief was fastened over his eyes. He was placed on a table. A three-quarter-inch rope tied by the hangman was lowered over a tree branch and around his neck.

The table was kicked from under his feet. Frank was lifted high in the air. The drop from the makeshift gallows opened the wound on his neck. The time was about 7:00 a.m., on August 17, 1915.

The word spread fast that Leo Frank had been hanged. Scores of people raced to the hanging site on foot, via bicycles, by horseback, and in what few autos then were available.

One of the first to arrive was a prominent young Mariettan who had been rejected as a lyncher because of his high temper and drinking habits. "We thank you, God, for allowing these men to do this grand and glorious deed," the rejected lyncher shouted, "but damn their souls for not letting me help. They won't put any monument over you (Frank). They are not going to get a piece of you as big as a cigar."

People with cameras snapped Frank's picture as his body swayed in the breeze. Picture post cards of the lynching were sold for years as souvenir items in Georgia stores. Pieces of Frank's clothing were cut away, the tree stripped of many low-hanging limbs, and the rope cut up and taken as souvenirs.

Marietta hardware stores sold out of rope after the hanging. Enterprising citizens bought the rope, cut in into pieces, and sold it as mementoes.

When Frank's body was cut down, a citizen tried to grind his shoe into Frank's face. Newt A. Morris, a former judge of the Blue Ridge Circuit, stepped forward to stop him and to quiet the crowd.

"Whoever did this thing left nothing more for us to do," Morris told the crowd. "Little Mary is vindicated; her foul murder is avenged. Now I ask you, I appeal to you as citizens of Cobb County, not to do more. I appeal to you to let this undertaker take it."

Morris soon was joined by Canton attorney John Wood, who later became a congressman, in appealing to the crowd. He helped Morris load the body into a basket and place it in a W. J. Black Funeral Home wagon that hauled it to the National Cemetery gate where it was placed in Wood's car and rushed to Atlanta.

At Ashby and Marietta Streets, an ambulance from Greenberg & Bond met Wood's wagon and took the body.

A crowd gathered around the funeral home, demanding to see the dead man's body. Fearing violence, police persuaded Mrs. Frank to consent. The crowds were allowed to view the body.

Later, Leo Frank's body was shipped to his parents' Brooklyn home and buried on August 20th in Mount Carmel Cemetery. Carved on his tombstone is the Latin phrase Semper Idem—which means "always the same, nothing changes."

Before the day's end, Fiddling John Carson was wailing on the courthouse steps:

Little Mary Phagan went to town one day,

And went to the pencil factory to see the big parade.

She left her home at eleven, A

nd kissed her mother good-bye,

Not one time did that poor child think T

hat she was going to die. Leo Frank met her, with a brutely heart we know,

He smiled and said, "Little Mary, Now you will go home no more."

He sneaked along behind her,

Till she reached the metal room,

He laughed and said, "Little Mary

you have met your fatal doom."

Ex-Governor Slaton and Mayor Woodward, of Atlanta, were in San Francisco on the day of the lynching.

On August 18 Slaton addressed the California Civic League and declared he preferred to have Frank lynched by a mob rather than by judicial mistake because "one reached the soul of civilization, the other merely reached the body."

Mayor Woodward addressed the California State Assessors' Association and declared that Frank had suffered a "just penalty for an unspeakable crime."

A Cobb County coroner's jury met on August 24, heard witnesses, and ruled that Frank was "hanged by persons unknown." A Cobb grand jury investigated the hanging for several days but said it couldn't identify any of the men involved. Several lynchers reportedly were members of the grand jury. No lyncher was ever arrested. The question lingers: why didn't Albert Lasker, main financial supporter, Adloph Ochs, owner of the New York Times, Louis Marshall President of the American Jewish Committee and Jacob Schiff, Wall Street Financier who spent thousands and thousands to promote Frank's innocence ever pursue justice against the lynchers?

Tom Watson sent the following telegram to Mariettan Robert E. Lee Howell: "There's life in the old land yet." He applauded the hanging: "In putting the sodomite murderer to death, the vigilance committee has done what the sheriff would have done, if Slaton had not been of the same mould as Benedict Arnold . . . Georgia is not for sale to rich criminals."

In the Jeffersonian, he raged:

The ominous triune combination which has so rapidly given our country a foreign complexion, is made up of Priest, Capitalist, and Jew. The Priest wants the illiterate papal slave of Italy, Poland and Hungary; the Capitalist wants cheap labor; and the Jew wants refuge from the race-hatred which he himself has engendered throughout Europe.

As yet, the South has not been deluged by the foreign flood; as yet, our native stock predominates, and the old ideals persist. With us, it is, as yet, dangerous for an employer of young girls to assume that he buys the girl, when he hires her. A Jew from the North, coming South to act as boss over one hundred girls, may fall into a fatal mistake by forgetting that he is no longer in Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, or New York. When such a Jew comes to Georgia, he is sure to run into trouble if he acts as though he believed he had a right to carnally use the persons of the girls who work for him.

That was the mistake made by Leo Frank, and it cost him his life.

And the mistake made by Jews throughout the Union, was that they made Frank's case a race issue in total, contemptuous and aggressive disregard of the question of guilt. They arrogantly asserted, and kept on asserting, that he had not had a fair trial, without ever offering a scintilla of evidence to prove it.

They tried to "run over" the people and the courts of Georgia, and we wouldn't let them do it.

That's all.

Leo Frank's wedding ring was delivered to O. B. Keeler, Marietta reporter for the Atlanta Georgian, at his Marietta home the following evening.

On Thursday, August 19, Keeler's account of the incident was published in the Atlanta Georgian. Some idea of the importance attached to the story may be gained from the prominence given the story.

The banner headline read "FRANK'S WEDDING RING RETURNED" across the top of page one. A two-column, three-line readout said "DYING WISH OF MOB'S VICTIM CARRIED OUT BY UNKNOWN MESSENGER," beneath the banner headline. The story was in twelve-point type; it occupied the two right-hand columns of page one and continued on page two, where it filled two more columns.

Keeler's first-person account read:

Old Books say if you put beneath your pillow an object that has been associated with tragedy, or any scene of great stress and profound emotional excitement—if such an object be placed near you while you sleep—you will dream the thing that gave the object its most terrible significance; the scene will be reconstructed for you, and the act reenacted.

This is not true. Not always true, at least. For in my pillow last night was the wedding ring of Leo M. Frank. And I dreamed of nothing that could concern him in any way.

And if any object in this world today has been close to tragedy and aligned with horror, it is the wedding ring of Leo M. Frank.

Keeler, who had covered every session of the trial for the Atlanta Georgian, then told of the many times he had seen the ring on Frank's finger during the trial and during Frank's stay of nearly two years in the Fulton County Tower.

Whatever is the truth of April 26, 1913, Leo M. Frank wore that ring at the National Pencil Factory that. And Leo Frank wore that ring on the dreadful ride to his doom, in the oak grove just outside of Marietta. And who will say the supreme moment of his agony was not when he took off that ring and stood up to die?

If ever an object was charged with tragedy, it is the wedding ring of Leo M. Frank. And it was in my pillow Wednesday night. And I dreamed a ridiculous little dream of being a kid again, at dancing school, and the waltz they were playing was "Beaming Eyes." So I should say there is not much to the old idea of psychic dream-influences.

Keeler related how the ring came into his possession:

It was a little later than 8:00 Wednesday evening, and I was in the front room of my small house at No. 303 Polk Street in Marietta [Today it is at the southwest corner of Polk Street and Powder Springs Connector].

I had just started the Victrola on a selection passionately adored by the two young members of my family - "The Robert E. Lee Medley," by a lively band. It is very lively and ragged.

The band had just got into full swing then there was a step on the veranda outside the open door, then a knock. I went to the door, opened the screen, and stepped out.

There was a man on the veranda. He had something white in his hand. The following dialogue took place:

"Is this Mr. O.B. Keeler?"

"It is."

"I have a note for you,'

That was all. He spoke clearly and deliberately. He handed me an envelope. He turned and walked down the steps and away in the dark. He wasted no time, but he was not in a hurry.

Keeler opened the envelope, which contained the ring and a typewritten note. He took the note to the dining room where there was a light at the table. The note read:

Frank's dying request was that his wedding ring be given to his wife. Will you see that this quest is carried out?

This note will be delivered to you by a man who you do not know and who does not know you. Make no effort to find out his identity.

Keeler wrote, "I am making no effort to find out his identity. And I am undertaking to deliver the ring to Mrs. Leo Frank. It is a trust."

On the following day, Keeler delivered the ring to Mrs. Frank in Atlanta. She denounced Keeler roundly, and accused him of being among the group of men who hanged her husband.

Keeler said that he had accepted the trust with mingled emotions. "It was because of something else—another circumstance, which I will tell too, because the outside world may find it of interest and perhaps of information concerning the county and town in which I live—Cobb County and Marietta—in which county and near which place Leo M. Frank was hanged at 7:05 o'clock the morning of Tuesday, August 17."

Keeler said he knew what bad things were being said by the newspapers of the state and he had an idea of what would be said by newspapers outside of it.

He related:

I am a newspaper man. But I am not writing this as a newspaper man. I am writing this as a man who has lived in Cobb County for twenty-five years. And I am telling it to the limit of my ability as a reporter and observer of some little experience.

In our home when the ring came was a guest—a young woman from Kansas City, Missouri. She had arrived the evening before, from the North. She had never been in the South before. She had read stories of the Frank Case in the Kansas City newspapers—which in the end made a great effort to show Frank's innocence.

This guest, you might say, was a "stranger within our gates." And the experience of the ring, following so closely the tragedy of the day before, had a tremendous effect on her. I sought an unbiased view. I found it—and the intelligent one.

She was saying:

"Why it is something out of a book—I can't believe such things happen, really. But . . . why—I SAW the man, myself . . . and the ring. I can't believe it, but I know it is so." I said: "What do you think about it now?"

And she told me: "I read about the Frank lynching coming down on the train from Nashville. And I wondered: What am I getting into—what sort of people are these? I knew it took place quite near where I was going. And it frightened me."

I said: "You reached this town exactly twelve hours after the hanging. Did it look like that kind of a town to you then?" She said: "It did not. I thought it was the quietest, most peaceful-looking little place I ever was in. I never met more kindly or hospitable or friendly people than at the party this afternoon. Why, I just know they are good people."

Of course, she hadn't met them all, having been in Marietta only twenty-five hours. But I have lived here the same number of years. And our opinions agreed exactly.

Explaining what he meant by "agreeing exactly," Keeler said: I know what was done to Leo M. Frank, in that oak grove, the morning of August 17. It is said that men of Cobb County did it. I do not know about that. But I do know what was done that morning.

Also I know what the people of Marietta did for me and my family when I lay near death from pneumonia last spring.

And then you see, I have lived among these people for twenty-five years.

And I know they are good people.

One of the "young members" Keeler referred to was his son, George Keeler. George Keeler related to me the events that occurred. He told me: "My father, the late O. B. Keeler, was on the staff of the Atlanta Georgian in 1913 and reported every session of the Frank trial for that newspaper, and he said many times there was never any doubt in his mind as to Frank's guilt. He said the defense did everything it could to lay the blame on the Negro janitor, Jim Conley.

"He said, 'Conley, an illiterate Negro, could not possibly have made up the complicated story he told of Frank's sexual adventures, a story the defense lawyers could not shake after days of hammering on him.' And, my father pointed out, Frank had the best lawyers in the state that money could buy.

"Two years later, and well into the night of August 16, 1915, a telephone call from the Georgian informed my father the paper had received a report that a group of men was headed for the State Prison at Milledgeville with the intention of seizing Frank and taking him to Marietta and there to hang him over the grave of Mary Phagan.

My father was instructed to go to the cemetery and await developments. "My father went to the cemetery, and when nothing happened by dawn, he proceeded to the Cobb County Courthouse on the City Square. Shortly after my father arrived at the Courthouse, a farmer came in and said, 'There's a bunch of men at Frey's Gin and they're up to something.' This was early morning of August 17, 1915.

"The next evening, about dusk, a stranger appeared at the Keeler home on Polk Street and handed my father an envelope. The envelope contained a typewritten note and a wedding ring. The note said the ring was Frank's, and requested my father to deliver the ring to his wife.

"The next day, August 19, 1915, my father delivered the ring to Mrs. Frank and wrote the account of how the ring had come into his possession and what he had done with it—in a story that was published that day in the Georgian under an eight-column banner headline on page one.

- Chapter 1 - "ARE YOU, BY ANY CHANCE...?" [Last Updated On: April 8th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 2 - The Legacy [Last Updated On: April 8th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 3 - My Search Begins [Last Updated On: April 8th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 4 - The Case for the Prosecution [Last Updated On: April 10th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 5 - The Case For The Defense [Last Updated On: April 18th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 6 - Sentencing And Aftermath [Last Updated On: February 19th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 7 - The Commutation [Last Updated On: January 3rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 9 - Reverberations [Last Updated On: January 1st, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 10 - Alonzo Mann's Testimony [Last Updated On: February 8th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 11 - The Phagans Break Their Vow Of Silence [Last Updated On: January 3rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Afterward - Pardon: 1986 [Last Updated On: January 3rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 12 - Application For Pardon, 1983 [Last Updated On: January 27th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2023]

- Selected Bibliography [Last Updated On: January 3rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 25th, 2023]

- Index of Sources [Last Updated On: January 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: January 1st, 2024]