Last Updated on April 18, 2024 by Mary Phagan

Hi

White Privilege is the unearned, mostly unacknowledged social advantage white people have over other racial groups simply because they are white. [Definition, Dictionary]

In 1913, Leo Frank was convicted for the murder of Little Mary Phagan based on the direct evidence found at the scene of the crime as well as circumstantial evidence and because he was a “sexual deviant/degenerate” with a long history of sexually molesting his female employees.

Leo Frank and his defense team used “White Privilege” as a tool to play on white fears about stereotypes of “Negroes” being savage beasts and pathological liars. [Footnote 12: Documented Sources]

Scholars of the case have admitted that Leo Frank and his supporters actually relied on racism to defend himself against charges they knew were true. Jewish historian Theodore Rosengarten bluntly asserted that “Readers who wish to find a progressive Jewish social ethic at work in the Frank camp will be sorely disappointed. Frank’s lawyers played the race card for all it was worth.” [Footnote 13: Theodore Rosengarten, "The Haunting Questions of a Murder and Lynching," NYT, Dec 19, 2003, E43]

Frank’s own racist thinking is reflected in an Atlanta Constitution frontpage headline on May 31, 1913: *Add newspaper clipping of title

Mary Phagan's Murder was Work of a Negro, Declares Leo M. Frank

The newspaper quoted Frank:

“Here is a negro, not alone with the shiftless and lying habits of an element of his race, that is common to the South…. No white man killed Mary Phagan. It’s a negro’s crime, through and through. No man with common sense would even suspect I did it.”

Documented Sources:

White Privilege and Leo Frank’s Racism

Harry Golden, A Little Girl is Dead

(1965), p. xv:

“Until the mid-1960s, let alone in1913, no white man in any of the old Confederate States had ever been convicted of a capital offense on the

testimony of a Negro.”

Robert Seitz Frey and Nancy

Thompson-Frey, The Silent and the

Damned (1988), p. 109:

“Leo Frank was convicted on the strength of a black man’s testimony—truly a rare event in the South in the early years of the twentieth century. Certainly, the words of a black man were almost never taken over those of a white man. And Frank was convicted by an all-white jury.”

Jeffrey Melnick, Black-Jewish Relations

on Trial: Leo Frank and Jim Conley in the

New South (2000), pages xi, 8, 37, 43, 61,

100, 111:

“…Frank and his supporters used racist language to demean Conley and took refuge in what they understood to be the privilege of Jewish whiteness.”

“This represented the first capital case in postbellum southern history in which a ‘white’ defendant was condemned by the testimony of an African American.”

“…Jews like Leo Frank were much more likely to take up whiteness as a self-concept and mode of behavior than their northern counterparts…”

“Frank considered himself to be white and enjoyed the privileges thereof, including African American

domestic help and control over a large number of poor southerners—white and African American.”

“Another of Frank’s lawyers referred to Conley as a ‘dirty, filthy, black, drunken, lying nigger.’”

“…Frank’s people tried to establish Frank’s ‘whiteness’ (and I mean that doubly here to signify his racial standing and his innocence) by demonstrating his distance from even the most trivial constituent of American culture that might be traceable to African Americans.”

“Frank’s lawyers employed racial epithets at every turn, and... capitalized on much the same sort of racist thinking that helped to turn public opinion against their man.”

Charles and Louise Samuels, Night Fell on Georgia (1956), pages 158, 159:

“Again it should be noted that the men defending Frank, while protesting the [nonexistent] prejudice against Jews, saw no reason why anyone should object to their own

often expressed prejudice against Negroes.”

“‘Who is Conley?’ [the defense lawyer Luther Rosser] demanded.

‘Who was Conley, as he used to be and as you have seen him? He was a dirty, filthy, black, drunken, lying nigger.’”

Steve Oney, And the Dead Shall Rise

(2003), page 148:

“For one thing, Leo Frank had already made the grounds of the impending legal battle clear. ‘No white man killed Mary Phagan,’ the factory superintendent had reportedly told a prison attaché upon hearing of Conley’s affidavits. ‘It’s a negro crime, through and through.’ The Negro to whom Frank was referring was, of course, poor Jim, and as [attorney William] Smith later phrased it, the accused was going to use every bit of his ‘great influence and unlimited financial means to bring the point home to a jury.”

Nation of Islam, The Secret Relationship

Between Blacks & Jews, Vol 3 (2016),

pages 125, 362:

“Frank’s attorneys seized upon the state’s extraordinary blurring of the color line to make their stand. They looked beyond the murder of

Mary Phagan and took the position that Frank’s conviction would in fact undermine sacred Southern racial traditions and set in motion a racial upheaval far more significant than Frank’s actual guilt or innocence.”

“Today’s believers in the innocence of Leo Frank have continued the tactic pursued in the courtroom by his lawyers, who assigned all manner of dishonesty to James Conley: Frank’s attorneys variously called Conley ‘a dirty, filthy, black, drunken, lying nigger’; ‘a dirty negro crook’; a ‘beastly, drunken, filthy, lying nigger’; a ‘filthy, criminal, lying negro’—being careful to pair untruthfulness and uncleanliness with the Black race.”

R. Barri Flowers, Murder Chronicles: Murder at the Pencil Factory, (2017); Page 31.

“Racism and stereotyping had been part of the defense strategy throughout the trial, as Frank’s attorneys portrayed Conley as being ‘especially disposed to lying and murdering because of his race.’”

Nancy MacLean, “The Leo Frank Case

Reconsidered” (1991), *Add page number

Characterizes Frank’s defense as: “a virulent racist offense against ... Jim Conley.” “Frank’s attorneys based their case on the most vicious antiblack stereotypes of the day on outspoken appeals to white solidarity...”

Dr. Stuart Rockoff, director of the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience:

“Thus, their defense of Frank was largely an asserting of his and, by extension, their own whiteness.” ["Jewish Racial Identity in Pittsburg and Atlanta, 1890-1930" (PhD, Univ. of Texas at Austin, 2000), 275.)]

Phagan Family Position Paper, June

2019, pages 7-9:

“Leo Frank’s lawyers argued to the jury of twelve white men that murder, rape, and robbery were ‘negro crimes’ and thus Frank, a white man, could not have committed the

murder of Mary Phagan. One defense

attorney said that ‘the murder was the

unreasoning crime of a negro,’ that ‘It isn’t a white man’s crime.’”

Albert S. Lindemann, The Jew Accused, (1991), page 245:

“Frank resorted to racial stereotypes in his own defense. He insisted that Mary must have been killed by some sort of violent, primitive brute—in short, a Black, not a Jew. Frank’s lawyers were energetic in insisting that murder of this sort was not a Jewish crime, and they did not hesitate to exploit anti-Black bigotry. They referred to Jim Conley…as a ‘dirty, filthy, black, drunken, lying nigger’...”

“There was something... hypocritical about such men, denouncing the bigoty against Jews that they asserted was responsible for the charges against Frank, yet resorting to a far more explicit and vicious bigotry against Blacks in his defense. Significantly, the prosecution avoided racial stereotyping, at least of this blatant sort.”

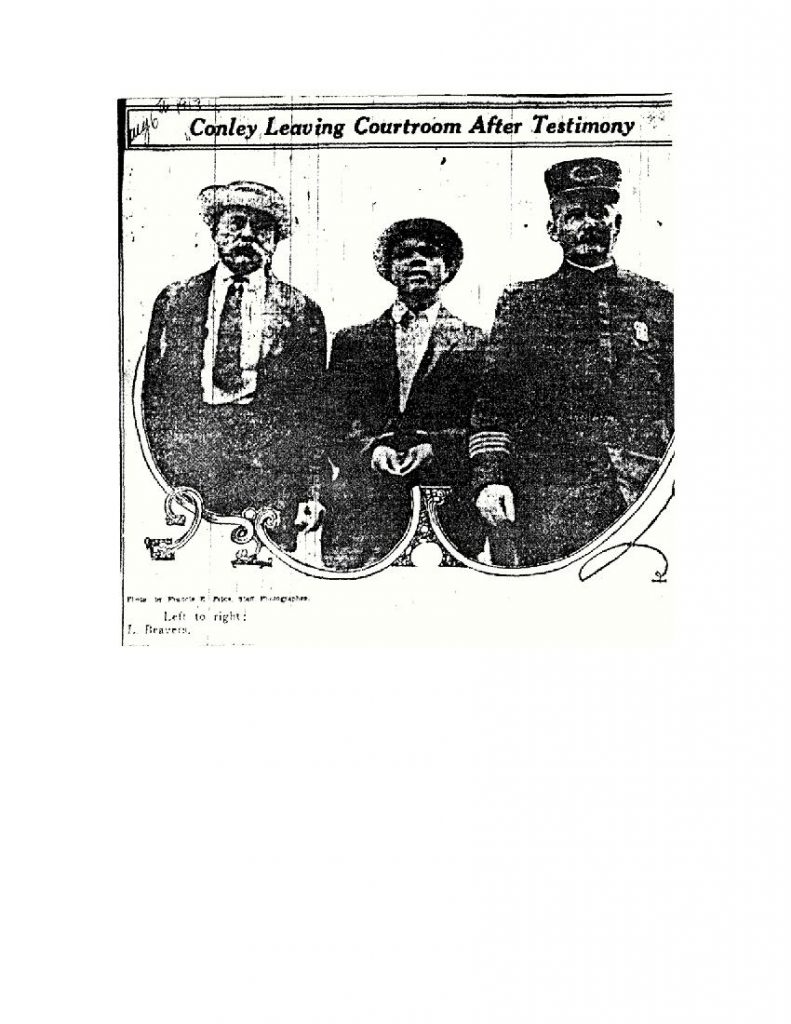

Leo Frank’s supporters then and now have played the White Privilege race card and falsely represent an African American man as the “real killer.” For 109 years James “Jim” Conley has been scapegoated in nearly all the literature on

the case. He was a sweeper in the factory

on the day of the murder who was ordered

by his boss Leo Frank to help move the

dead body of Mary Phagan. When Conley

confessed to his accessory-after the-fact role, Frank and his supporters tried (and continue

to this day) to smear Conley as a devious criminal who got away with murder, but Conley’s very detailed confession corroborated

by the physical evidence at the crime scene—was so convincing that it became central to the

prosecution’s case. (At trial, Leo Frank refused to be cross-examined by prosecutors, but James Conley withstood nearly 16 hours of cross-examination—under oath.)

Before he accused James Conley of the

crime, Leo Frank worked overtime to pin

the murder on the African American night

watchman who found Mary Phagan’s body,

Newt Lee. Frank hired private detectives

who planted a blood-soaked shirt in the

innocent black man’s home, and then

Frank told the police where they could

find that damning “evidence.” When the

newspapers reported that a bloody shirt

was found at Lee’s home, it almost caused

an innocent man to be lynched. Luckily

for Lee, Frank’s private detectives did

such a sloppy job at planting the shirt

that the police were not fooled at all, and

it only increased their suspicion of Leo

Frank. That is the point when the people of

Atlanta came to believe—and rightly so—

that Leo Frank was the murderer of Little

Mary Phagan.

Leo Frank: “Sexual Pervert”

According to Dr. Jeffrey Melnick, “The

perversion charge merits special attention

because it formed the emotional core of the

prosecution’s case against Frank, and also

became the most important constituent in

public feeling against him.” So, according

to the Nation of Islam,

“The Frank team strategy was to stress the act of rape in Mary Phagan’s murder, and in so doing the Frank team felt they could convince a predisposed white America that only a Black man could be responsible for the brutal

killing of this white girl.”

Dr. Stuart Rockoff concurs:

“Frank’s trial lawyers also relied upon the stereotype of the black rapist to argue that Conley was the one most likely guilty of the crime.”

By the time of his hanging in 1915 many people—including his Jewish supporters—not only were repelled by Leo Frank’s abrasive personality but also believed he was in fact the murderer of Mary Phagan. Chicago icon Albert Lasker, a Jewish philanthropist and the “father

of modern advertising,” paid millions (in

today’s money) for Frank’s defense, but he

privately admitted that he was not even

convinced that Leo Frank was innocent. *Add source

It was Lasker who financed all of Frank’s post-conviction appeals and orchestrated his international public relations campaign that involved media outlets across the nation, including the New York Times. Lasker recalled the meeting in Frank’s jail cell:

“It was very hard for us to be fair to him, he impressed us as a sexual pervert. Now, he may not have been—or rather homosexual or something like that…”

According to Lasker’s biographer, the

men with him during that encounter took “a

violent dislike to him.” Lasker “hated him,”

and said, “I hope he [Leo Frank] gets out…

and when he gets out I hope he slips on a

banana peel and breaks his neck.”

The fact is Leo Frank was a sexual predator—the Harvey Weinstein/Jeffrey Epstein of

his era. He, like those convicted pedophiles, used the factory he managed and the position

he held to pressure little girls into sexual situations where he ruthlessly took advantage of them. And that is exactly what he did on

Saturday, April 26, 1913, to thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan, who came to her place of employment to collect her pay of $1.20 from her boss Leo Frank.. And just like Harvey Weinstein and Jeffrey Epstein, B’nai B’rith president Leo Frank used the opportunity to lure Little Mary Phagan to a back area of the factory and attempted to sexually assault her.

Evidence shows that Mary resisted Frank

with all of her might and in the struggle he

struck her and then strangled her to death.

At his murder trial twenty of Leo Frank’s own female employees bravely took the witness stand and testified to Frank’s history of sexual deviance and harassment. They testified that he “got too familiar,” put his hands on” them, tried to corner them, and proposed sexual acts to them for money. Fourteen-year-old Nellie Pettis recounted how Frank had propositioned

her for sex and 16-year-old Nellie Wood

testified that Frank pushed himself against

her and touched her breast. Several male

employees also described how they had

witnessed Frank rubbing himself against young female workers. The testimony was so explicit that the judge had to clear the courtroom of women.

These young girls were the real pioneers of today’s #MeTooMovement.

Leo Frank’s lawyers did not even attempt to cross-examine any of the girls who testified at his trial. Instead, the defense attorneys told

the jury that Frank’s behavior was: “a sign that we are getting more broad-minded... Deliver me from one of these prudish fellows that never

looks at a girl and never puts his hands on her.... He’s the kind that I wouldn’t trust behind the door.”

Defense Team Theory: Jim Conley Assaulted Mary Phagan on the first floor lobby of the National Pencil Company and then threw her down the elevator shaft or scuttle hole two feet by two feet and three inches-or about four and one-half square, feet. Time theory. Clark Woodenware theory.

At the Trial of Leo Frank, the Defense suggested the theory that Jim Conley may have assaulted and then thrown an unconscious Mary Phagan, 14 feet down the elevator shaft, or through the scuttle hole at the side of the elevator or crowded back into the former location of the Clark Woodenware Company that had departed January 17, 1913 from its first floor office space that was locked off. The problem with the three defense theories, was that had Phagan at 4’11” tall and 107lbs, had been thrown down the 14 foot elevator shaft or scuttle hole while she was unconscious, there would have been clear identifiable forensic medical evidence of it on her body to indicate as such, and it would have been reported by the defense and prosecution examining physicians. But no physical evidence was found on Mary Phagan to suggest when she was alive, if and when her body was theoretically thrown down the elevator shaft or scuttle hole. Moreover, the drag marks found on the basement floor, beginning at the entryway of the elevator shaft, had tended to rule-out the scuttle hole. The Clark Woodenware theory was ruled out because the door to their area had been locked by the owner of the building, and no one but him had access to that area. The National Pencil Company was a rented building. Interestingly enough, the lobby entry door to the former Clark Woodenware company was broken open 4 days after the murder, so that the Frank defense could use it as one of their three theories of how Jim Conley could have murdered Phagan..

The location of the trap door, and its distance from the second floor and Frank's office, is also important. That door is just behind the elevator box or shaft, and about eight (8) feet to the right of the bottom step of the stairs. It is just across the little hallway there from the steps, and not in front of the steps. This hatchway or scuttle hole, is two feet by two feet and three inches-or about four and one-half square, feet. It closes with a door that fits into the floor and that can be easily lifted up. From this, down to the dirt floor of the basement, is a ladder-not stairs-made of two scantlings and a great number of rungs or rounds. The basement is deep-the ladder about twelve feet long. The basement has a dirt floor. It is very dirty from the coal dust, ashes, cinders-almost anything that makes dirt in such a place. This is where Dalton says he went with a woman- while Jim Conley watched for him-"a mighty nasty, place to take a woman." Yet, while some people are depraved themselves, they are still in favor of social equality-want to put everybody on a level-and having no desire to rise up themselves, would pull every-body else down to their level. At every single time he says he went down that scuttle, that floor, back and front, was occupied by the Wooden Ware Company.

Now the much-discussed scuttle hole has a trap door that fits down close over it. This is just back of elevator shaft and about 8 feet from where one would come down the stairs from the second floor.

Blunt force trauma will be the most common, although it could be other things.

There will almost certainly be massive skeletal damage, and internal bleeding, that can be enough. But depending on the fall, the organs are probably too damaged to continue functioning - with or without blood.

A fall from 14 feet can cause serious injuries or even death, depending on various factors such as the surface landed on, the position of the body upon impact, and the age and health of the person. Some potential injuries from a fall include fractures, sprains, head injuries, and internal organ damage. The autopsy report indicated none of these injuries.

Perhaps the most important element of Leo Frank's defense concerned time. If, as Jim Conley testified, Mary Phagan had come to the pencil factory before Monteen Stover, she had to arrive there before 12:05. Ms. Stover testified that was the time she arrived. But the motorman and conductor of the trolley asserted that Mary Phagan had gotten off at 12:10. Either Conley or Stover was incorrect. Most witnesses, including Conley, agreed that it would have taken, at best, one half hour for the murder and movement of the body to the cellar, the writing of the murder notes, and Conley's hiding in the wardrobe, to occur. But there were only thirty to 45 minutes, between 12:00 and 12:45, that Frank's time was not accounted for.

Had Frank enough time to commit the murder and move the body? It was a question that many people, including me, asked themselves over and over again.

Thinking over that anomaly, I felt weary. How difficult it was seventy years later to understand the meaning of these inconsistencies. Yet, difficult as it was, I was determined to go on to try to piece together from the newspapers' accounts, the trial transcript, and the evidence my family had gathered the real truth about my great-aunt's death.

Making that resolution once again, I returned to the transcript and Leo Frank's contentions.

According to his pre-trial statements, Frank claimed that he was in his office continuously from noon to 12:35 on the day of the murder, but a witness friendly to Frank, 14-year-old Monteen Stover, said Frank’s office was totally empty from 12:05 to 12:10 while she waited for him there before giving up and leaving. This was approximately the same time as Mary Phagan’s visit to Frank’s office and the time she was murdered. On Sunday, April 27, 1913, Leo Frank told that Mary Phagan came into his office at 12:03 PM. The next day, Frank made a deposition to the police, with his lawyers present, in which he said he was alone with Mary Phagan in his second-floor business office between 12:05 and 12:10, maybe 12:07 according to Leo Frank in State's Exhibit B, given to the police on Monday, April 28,1913. At the Coroner's Inquest Frank stated that Mary Phagan arrived on his second-floor business office at 12:10 PM on April 26, 1913.

Leo Frank contradicted his own testimony when he finally admitted on the stand that he had possibly "unconsciously" gone to the Metal Room bathroom between 12:05 and 12:10 PM on the day of the murder.

Frank had gotten to the factory on the day of the murder at 8:30 a.m. At approximately 9:40, he had gone to Montag Brothers and returned to the factory at 10:55. He left the factory at 12:45 or 12:50, going home for lunch. At about 3:00 he returned, staying at the factory until 6:00. Upon going home at 6:25, he had dinner, was visited by some friends, and went to sleep about 10:30. He learned of the murder the next morning.

The defense called more than twenty witnesses to corroborate Frank's version of when the murder happened, where Frank had been, and at what time.

The first two witnesses, W. H. Matthews, motorman, and W. T. Hollis, conductor of the English Avenue car, testified that Mary Phagan got on at Lindsey Street at about 11:50 and was alone. The scheduled arrival time was seven and a half after twelve and the car was running on time on April 26.

On cross-examination, Hollis admitted that the English Avenue car time schedule was a hard one to maintain and that the company could suspend men for running ahead of time.

Then Herbert Schiff, assistant superintendent of the pencil factory, testified to the system of business, the preparation of the financial sheet, the procedure for paying off employees, and how the pencils are made. He remembered paying off Helen Ferguson and said he was the one, not Frank, who paid off on Friday, April 25. "Helen Ferguson did not ask for Mary Phagan's pay Friday, April 25." He also stated, "There was no bed, cot, lounge, or sofa anywhere in the building." And later said, "I have never seen Mr. Frank talk to Mary Phagan." On cross examination, Schiff said that "On Monday, Mrs. White claimed she saw a Negro man."

Among the witnesses to testify about Frank's action on that Saturday were:

Miss Mattie Hall, stenographer for Montag, the company Frank alleged he visited on Saturday morning, who testified that "I finished my work, left around 12:02 and punched the clock."

Although she admitted she testified differently at the inquest, she testified that Frank did not make up the financial sheet that Saturday morning.

Miss Corinthia Hall swore that she was the forelady for the factory and got there Saturday around 11:35 a.m. with Mrs. Emma Clark Freeman. Frank was in his office when they left around 11:45. On cross-examination she testified that she and Mrs. Freeman met Lemmie Quinn at the Greek Cafe. He told then that he had just finished seeing Frank.

Mrs. Freeman's testimony gave evidence to the same effect.

Miss Magnolia Kennedy swore that she was behind Helen Ferguson and Helen Ferguson did not ask for Mary Phagan's pay envelope.

On cross-examination, she stated: "Barrett called my attention to the hair. It looked like Mary's. My machine was right next to Mary's. Mary's hair was a light brown, kind of sandy color." She did not see the blood spots on the floor, but, she said, "You could plainly see the dark spots and white spot over it ten or twelve feet away."

Wade Campbell, another employee, was the brother of Mrs. White, who told him about seeing the Negro on Saturday. "I saw the spots they claim was blood. I couldn't say whether it was blood or not."

On cross-examination, he said, "It is not unusual to see spots all over the metal room floor." Further, he stated, "I have never seen Frank talk to Mary Phagan."

Lemmie Quinn, foreman of the factory, testified that one hundred women worked at the factory: "We have some blood spots quite frequently when people get their hands cut." However, he said, "I noticed the blood spots at the ladies' dressing room on Monday." Further, he declared, "I was in the office and saw Mr. Frank between 12:20 and 12:25."

Several witnesses later testified that Quinn advised them he had visited Frank prior to noon in the factory the Saturday of the murder.

Harry Denham, one of the carpenters on the fourth floor, testified that he was hammering about forty feet from the elevator. "I am sure that the elevator did not run that day, as I could have seen the wheels moving and heard the noise." He completed his work about 3:00 p.m. and left.

A testimony that caused further speculation was that of Minola McKnight, the cook for the Selig's, who testified:

I work for Mrs. Selig. I cook for her. Mr. and Mrs. Frank live with Mr. and Mrs. Selig. His wife is Mrs. Selig's daughter. I cooked breakfast for the family on April 26th. Mr. Frank finished breakfast a little after seven o'clock. Mr. Frank came to dinner about twenty minutes after one that day. That was not the dinner hour, but Mrs. Frank and Mrs. Selig were going off to the two o'clock car. They were already eating when Mr. Frank came in. My husband, Albert McKnight, wasn't in the kitchen that day between one and two o'clock at all. Standing in the kitchen door you can-not see the mirror in the dining room. If you move up to the north end of the kitchen, where you can see the mirror, you can't see the dining room table. My husband wasn't there all that day. Mr. Frank left that day sometime after two o'clock. I next saw him at half past six at supper. I left about eight o'clock. Mr. Frank was still at home when I left. He took supper with the rest of the family. After this happened the detectives came out and arrested me and took me to Mr. Dorsey's office, where Mr. Dorsey, my husband, and an-other man were there. I was working at the Selig's when they come and got me. They tried to get me to say that Mr. Frank would not allow his wife to sleep that night and that he told her to get up and get his gun and let him kill himself, and that he made her get out of bed. They had my husband there to bull-doze me, claiming that I had told him that. I had never told him anything of the kind. I told them right there in Mr, Dorsey's office that it was a lie. Then they carried me down to the stationhouse in the patrol wagon. They came to me for another statement about half past eleven or twelve o'clock that night and made me sign something before they turned me loose, but it wasn't true. I signed it to get out of jail, because they said they would not let me out. It was all written out for me before they made me sign it.

On cross-examination she was shown a copy of her original statement and said:

I signed that statement, but I didn't tell you some of the things you got in there. I didn't say he left home about three o'clock. I said somewhere about two. I did not say he was not there at one o'clock. Mr. Graves and Mr. Pickett, of Beck & Gregg Hardware Co., came down to see me. A detective took me to your [Hugh Dorsey's] office. My husband was there and told me that I had told him certain things. Yes, I denied it. Yes, I wept and cried and stuck to it. When they first brought me out of jail, they said they did not want anything else but the truth, then they said I had to tell a lot of lies and I told them I would not do it. That man sitting right there [pointing to Mr. Campbell] and a whole lot of men wanted me to tell lies. They wanted me to witness to what my husband was saying. My husband tried to get me to tell lies. They made me sign that statement, but it was a lie. If Mr. Frank didn't eat any dinner that day I ain't sitting in this chair. Mrs. Selig never gave me no money. The statement that I signed is not the truth. They told me if I didn't sign it they were going to keep me locked up. That man there [indicating] and that man made me sign it. Mr. Graves and Mr. Pickett made me sign it. They did not give me any more money after this thing happened. One week I was paid two week's wages.

Finally, when the defense requestioned her, she declared:

None of the things in that statement is true. It's all a lie. My wages never have been raised since this thing happened. They did not tell me to keep quiet. They [the Selig's] always told me to tell the truth and it couldn't hurt.

Mrs. A. P. Levy testified that she saw Frank get off the trolley car on Memorial Day between one and two o'clock. Her cross-examination stated that it was definitely 1:20 because she was looking at the clock.

Mrs. M. G. Michael of Athens testified that she saw Frank at two o'clock that day and observed nothing unusual about him. Her husband, Jerome Michael, stated that he saw Frank between one and two o'clock and noticed absolutely nothing unusual about him. "No scratches, bruises, marks, and no nervousness."

Mrs. Hennie Wolfsheimer swore to the same thing. She was Frank's aunt and was corroborated by Julian Loeb, a cousin to Mrs. Frank, as well as by Cohen Loeb and H. J. Hinchey.

Emil Selig, Frank's father-in-law, testified to Leo Frank's natural conduct:

My wife and I live with Mr. Frank and his wife. The kitchen in our house is next to the dining room. There is a small passageway between them. The sideboard in the dining room is in the same position now as it has always been. Mr. Frank took breakfast before I did on April 26th and left the house before I breakfasted. I got back home to dinner at about 1:15. My wife and Mrs. Frank were eating then. They told me in the morning to come home a little sooner, that they wanted to go to Grand Opera that afternoon and have dinner a little earlier than usual, and I came home a little earlier. Mr. Frank came in after I did, about 1:20. There was nothing unusual about him. No scratches or bruises about him. He sat down to his meal. The ladies left us while he was still eating. I don't know what Mr. Frank did after dinner. I went out to the chicken yard. Mr. Frank was still in the hall when I got back. I laid down and went to sleep. I did not see him when he left. I saw him about 6:30 that evening. Mrs. Frank and Mrs. Selig had not yet gotten back. They came in a short while. We ate supper about seven o'clock. I noticed nothing unusual about him at supper. We finished supper about seven twenty-five. Mr. Frank sat in the hall and read. A party of our friends came to the house and played cards after supper. Frank and his wife did not play. They don't play poker. They play bridge. He was reading in the hall while we were playing. He came in one time while we were playing and said he read a story about a baseball umpire's decision, and he was laughing. Frank answered the doorbell several times that evening when the guests came. He and his wife went to bed before the company left, about ten or ten-thirty. He came to the door and told us goodnight and went upstairs. His wife went up shortly afterwards.

Mrs. Rhea Frank, Frank's mother, took the stand. On cross-examination, she stated, "Leo does not have any rich relatives in Brooklyn." Later she said,

As to what my means of support are, we have about $20,000, out at interest, my husband and I, at six per cent. We own the house we live in. We have a $6,000 mortgage on it. The house is worth about $10,000. My husband is doing nothing. He is not in good health. Up to a year ago he was a traveling salesman. These are the only relatives my son has in Brooklyn. Mr. Moses Frank, my brother-in-law, generally spends a Sunday with us in Brooklyn, before he sails for Europe. He spends Sunday with us in Brooklyn and has dinner with us. He was not in Brooklyn on April 26th. He is supposed to be very wealthy. I don't know how much cash my husband has in [the] bank. A few hundred dollars possibly. My husband is 67 years old. He is broken down from hard work and in very poor health. He was too unwell to come down here.

C. F. Urssenbach, Frank's brother-in-law, said he had an engagement with Frank to go to the ballgame on Saturday, but Frank called and cancelled it.

L. Strauss testified that he was at the Selig home Saturday night playing cards and that Frank sat in the hall reading.

Sig Montag, the treasurer of the factory, testified to Frank's coming to him Sunday morning after the murder and he looked all right. He went to the pencil factory that morning, and he called Mr. Haas, his personal counsel.

In total, the defense produced nearly two hundred witnesses, all white and principally from Atlanta, who largely corroborated Frank's version of what had happened the day of the murder and to discredit the state's witnesses. In addition, so as to offset the testimony concerning sexual liaisons in the factory as well as Frank's alleged misconduct with female employees, the defense was determined to establish Frank's good character, which, of course, carried with it the opportunity for the prosecution to introduce subsequent evidence as to Frank's alleged bad reputation and character.

Jim Conley's reputation and past experiences, including his drinking habits, problems with the law, and history of petty theft and disorderly conduct, were heavily attacked by the defense lawyers and witnesses. The core of this focus was the question: could Jim Conley be believed?

Mrs. Rebecca Carson, a forelady at the pencil factory, testified that the elevator was noisy when it ran and that Jim Conley told her on Monday he was so drunk the previous Saturday he did not know where he was or what he did. She also stated that she overheard Jim say that "Frank is innocent as an angel; and when my mother said 'The murderer will be the Negro Mrs. White saw sitting on a box at the foot of the stairs,' Jim dropped his broom quick and didn't finish sweeping."

Mrs. E. M. Carson testified that she saw blood spots around the ladies dressing room three or four times later she recalled that Conley said, "Mr. Frank is as innocent as you is, and I know you is." She told Conley that "Whenever they find the murderer of Mary Phagan it's going to be the 'nigger' that was sitting near the elevator when Mrs. White went upstairs." "Further," she said, "I would not believe Conley on oath."

Miss Mary Pirk, another forelady at the factory, testified "I talked with Jim Conley the Monday after the murder. I accused him of the murder and he took his broom and walked right out of the office." She swore that she wouldn't believe Jim on oath.

On cross-examination, Miss Pirk stated that she did not tell Frank of her suspicions and that she suspected Jim "because he looked and acted so differently."

I accused Jim before I saw the blood at the ladies' dressing room. It was all smeared over with some kind of white stuff. It covered about two feet in area. I mentioned it to the girls before Jim was arrested. I am not sure whether it was before or after. It was after the Coroner's inquest. I have seen several spots in the factory that looked like that spot many times. All kinds of spots. I have seen spots before that looked like that. I don't know exactly when. My opinion is that Mr. Frank is a perfect gentleman. I always found him to be one in my dealings with him. I have never heard any of the girls say anything about him.

Another important defense witness was Daisy Hopkins. She had been named by Jim Conley as one of the girls Dalton and Frank brought to the factory for immoral purposes:

I am a married woman. I worked in the factory from October 1911 to June 1st, 1912. I worked in the packing department on the second floor. Mr. Frank never spoke to me when he would pass. I never did speak to him. I've never been in his office drinking beer, Coca-Cola, or anything else. I know Dalton when I see him. I never visited the factory with him, I never have been with him until I went to his to see Mrs. Taylor, who lived with him then. That was the only place I have ever seen him. I never have been to the factory on Saturday or any other day. I never introduced him to Mr. Frank. There isn't a word of truth in that. I have never gone down in the basement with this fellow, Dalton. I don't even know where the basement is at all. I have never been anywhere in the factory, except at my work.

It was brought out under cross-examination by Dorsey that Mrs. Hopkins had been arrested but not tried for fornication. She said:

I have never been in jail. Mr. W.W. Smith got me out of jail. Somebody told a tale on me, that's why I was put in jail. I don't know what they charged me with, they accused me of fornication.

On redirect examination, she stated:

I never was tried. I never had to pay anything except my lawyer's fee, which I paid to Mr. William Smith. I never was taken to court.

Miss Dora Small testified that she worked at the factory and saw Jim Conley on the fourth floor Tuesday. "I did not see Frank talk to Conley," she said. Later, she said, "Jim worried me with money so he could buy a newspaper, and every time he heard a newsboy yell 'Extra!' Jim would go to me and beg to see the paper before I finished reading." She continued by stating that Conley's reputation for truth and veracity was bad.

Miss Julia Fuss said, after being sworn in, "I work on the fourth floor of the factory and I talked to him (Conley) Wednesday morning after the murder. He told me he believed Mr. Frank was just as innocent as the angels from heaven." Further she said, "Jim was never known to tell the truth."

On cross-examination, she testified that Frank came up the stairs Tuesday where Conley was but she did not see them talking.

In all, forty-nine women employees at the pencil factory testified that Leo Frank's general reputation and his reputation for moral rectitude was good.

No one realized when Alonzo Mann, Frank's office boy, testified that it would be his revelations sixty-nine years later which brought the Leo Frank-Mary Phagan murder case once again into national prominence.

I am office boy at the National Pencil Company. I began working there April 1, 1913. I sit sometimes in the outer office and stand around in the outer hall. I left the factory at half past eleven on April 26th. When I left there Miss Hall, the stenographer from Montag's, was in the office with Mr. Frank. Mr. Frank told me to phone Mr. Schiff and tell him to come down. I telephoned him, but the girl answered the phone and said he hadn't got up yet. I telephoned once. I worked there two Saturday afternoons of the weeks previous to the murder and stayed there until half past three or four. Frank was always working during that time. I never saw him bring any women into the factory and drink with them. I have never seen Dalton there. On April 26, I saw Holloway, Irby, McCrary and Darley at the factory. I didn't see Quinn. I don't remember seeing Corinthia Hall, Mrs. Freeman, Mrs. White, Graham, Tillander, or Wade Campbell. I left there eleven-thirty. [See Chapters 10 and 12 for complete testimony of Alonzo Mann]

Despite Jim Conley's allegations that Leo Frank had said, "You know I ain't built like other men;" several physicians who examined Frank during his incarceration testified that he was anatomically normal. Other physicians tried to ascertain more precisely the exact time of Mary Phagan's death by giving their opinions on the digestive processes entailed after Mary's last meal, but they were largely unsuccessful as there was much difference of opinion.

Fifty-six associates of Frank at Cornell University, in Brooklyn, and in Atlanta testified as to his general good character as an upright and law-abiding citizen.

Georgia law in 1913 stipulated that no defendant could be sworn to testify for himself. Judge Roan read Frank the law: "In criminal procedure the prisoner will have the right to make to the court and jury such statement in the case as he shall deem proper in his defense. It shall be not under oath and shall have such force as the jury shall think right to give it. They may believe it in preference to sworn testimony. The prisoner shall not be compelled to answer any questions on cross-examination. He should feel free to decline to answer. Now you can make such statements as you see fit."

Concluding the defense's case, Frank submitted a lengthy statement on the stand August 18, 1913, and he refused to be cross-examined. He spoke for four hours:

"Gentlemen of the Jury: In the year 1884, on the 17th day of April, I was born in Paris, Texas. At the age of three months, my parents took me to Brooklyn, New York, and I remained in my home until I came South, to Atlanta, to make my home here. I attended the public schools of Brooklyn, and prepared for college at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York. In the fall of 1902, I entered Cornell University, where I took the course in mechanical engineering, and graduated after four years, in June, 1906. I then accepted a position as draftsman with the B.F. Sturtevant Company, of High Park, Massachusetts. After remaining with this firm for about six months, I returned once more to my home in Brooklyn, where I accepted a position as testing engineer and draftsman with the National Meter Company of Brooklyn, New York. I remained in this position until about the middle of October, 1907, when, at the invitation of some citizens of Atlanta, I came South to confer with them in reference to the starting and operation of a pencil factory, to be located in Atlanta. After remaining here for about two weeks, I returned once more to New York, where I engaged passage and went to Europe. I remained in Europe nine months. During my sojourn abroad, I studied the pencil business, and looked after the erection and testing of the machinery which had been previously contracted for. The first part of August, 1908, I returned once more to America, and immediately came South to Atlanta, which has remained my home ever since. I married in Atlanta, an Atlanta girl, Miss Lucile Selig. The major portion of my married life has been spent at the home of my parents-in-law, Mr. and Mrs. E. Selig, at 68 East Georgia Avenue. My married life has been exceptionally happy—indeed, it has been the happiest days of my life. . . .

On my arrival at the factory, I found Mr. Holloway, the day watchman, at his usual place, and I greeted him in my usual way; I found Alonzo Mann, the office boy, in the outer office. I took off my coat and hat and opened my desk and opened the safe, and assorted the various books and files and wire trays containing the various papers that were placed there the evening before, and distributed them in their proper places about the office. I then went out to the shipping room and conversed a few minutes with Mr. Irby, who at that time was shipping clerk, concerning the work which he was going to do that morning, though, to the best of my recollection, we did no shipping that day, due to the fact that the freight offices were not receiving any shipments, due to its being a holiday. I returned to my office and looked through the papers, and assorted out those which I was going to take over on my usual trip to the General Manager's office that morning. . . . Of all the mathematical work in the office of the pencil factory, this very operation, this very piece of work that I have now before me, is the most important, it is the invoices covering shipments that are sent to customers, and it is very important that the prices be correct, that the amount of goods shipped agrees with the amount which is on the invoice, and that the terms are correct, and that the address is correct, and also in some cases, I don't know whether there is one like that here, there are freight deductions, all of which have to be very carefully checked over and looked into, because I know of nothing else that exasperates a customer more than to receive invoices that are incorrect; moreover, on this morning, this operation of this work took me longer than it usually takes an ordinary person to complete the checking of the invoices, because usually one calls out and the other checks, but I did this work all by myself that morning, and as I went over these invoices, I noticed that Miss Eubanks, the day before, had evidently sacrificed ac-curacy to speed, and every one of them was wrong, so I had to go alone over the whole invoice, and I had to make the corrections as I went along, figure them out, extend them, make deductions for freight, if there were any to be made, and then get the total shipments, because, when these shipments were made on April 24th, which was Thursday, this was the last day of our fiscal week, it was on this that I made that financial sheet which I make out every Saturday after-noon, as has been my custom, it is on this figure of total shipments I make that out, so necessarily it would be the total shipments for the week that had to be figured out, and I had to figure every invoice and arrange it in its entirety so I could get a figure that I would be able to use. . . .

I started on this work, as I said, and had gone into it in some detail, to show you the carefulness with which the work must be carried out. I was at work on this one at about nine o'clock, as near as I remember, Mr. Darley and Mr. Wade Campbell, the inspector of the factory, came into the outer office, and I stopped what work I was doing that day on this work, and went to the outer office and chatted with Mr. Darley and Mr. Campbell for ten or fifteen minutes, and conversed with them, and joked with them, and while I was talking to them, I should figure about nine fifteen, a quarter after nine, Miss Mattie Smith came in and asked me for her pay envelope, and for that of her sister-in-law and I went to the safe and unlocked it and got out the package of envelopes that Mr. Schiff had given me the evening before, and gave her the required two envelopes, and placed the remaining envelopes that I got out, that were left over from the day previous, in my cash box, where I would have them handy in case others might come in, and I wanted to have them near at hand without having to jump up and go to the safe every time in order to get them; I keep my cash box in the lower drawer on the left hand side of my desk. After Miss Smith had gone away with the envelopes, a few minutes, Mr. Darley came back with the envelopes, and pointed out to me an error in one of them, either the sister-in-law of Miss Mattie Smith, she had gotten too much money, and when I had deducted the amount that was too much, that amount balanced the payroll, the error in the payroll that I had noticed the night before, and left about five or ten cents over; those things usually right themselves anyhow. I continued to work on those invoices, when I was interrupted by Mr. Lyons, Superintendent of Montag Brothers, coming in, he brought me a pencil display box that we call the Panama assortment box, and he left it with me, he seemed to be in a hurry, and I told him if he would wait for a minute I would go over to Montag Brothers with him, as I was going over there; and he stepped out to the outer office, and as soon as I come to a convenient stopping place in the work, I put the papers I had made out to take with me in a folder, and put on my hat and coat and went to the outer office, when I found that Mr. Lyons had already left. Mr. Darley left with me, about nine thirty-five or nine forty, and we passed out of the factory, and stopped at the corner of Hunter and Forsyth Streets, where we each had a drink at Cruickshank's soda fount, where I bought a package of favorite cigarettes, and after we had our drink, we conversed together there for some time, and I lighted a cigarette and told him good-bye, as he went in one direction, and I went on my way then to Montag Brothers where I arrived, as nearly as may be, at ten o'clock, or a little after; on entering Montag Brothers, I spoke to Mr. Sig Montag, the General Manager of the business, and then the papers which I collected, which lay on his desk, I took the papers out and transferred them into the folder, and distributed them at the proper places at Montag Brothers. I don't know just what papers they were, but I know there were several of them, and I went on chatting with Mr. Montag, and I spoke to Mr. Matthews, and Mr. Cross, of the Montag Brothers, and after that I spoke to Miss Hattie Hall, the pencil company's stenographer, who stays at Montag Brothers, and asked her to come over and help me that morning; as I have already told you, practically every one of these invoices was wrong, and I wanted her to help me on that work, and in dictating the mail; in fact, I told her I had enough work to keep her busy that whole afternoon if she would agree to stay, but she said she didn't want to do that, she wanted to have at least half a holiday on Memorial Day. I then spoke to several of the Montag Brothers' force on business matters and other matters, and after that I saw Harry Gottheimer, the sales manager of the National Pencil Company, and I spoke at some length with him in reference to several of his orders that were in work at the factory, there were two of his orders especially that he laid special stress on, as he said he desired to ship them right away, and I told him I didn't know how far along in process of manufacture the orders had proceeded, but if he would go back with me then I would be very glad to look for it, and then tell him when we could ship them, and he said he couldn't go right away, he was busy, but he would come a little later, and I told him I would be glad for him to come over later that morning or in the afternoon, as I would be there until about one o'clock, and after three. I then took my folder and returned to Forsyth Street alone. On arrival at Forsyth Street, I went to the second or office floor, and I noticed the clock, and it indicated five minutes after eleven o'clock. I saw Mr. Holloway there, and I told him he could go as soon as he got ready, and he told me he had some work to do for Harry Denham and Arthur White, who were doing some repair work up on the top floor, and he would do the work first. I then went into the office, I went into the outer office, and found Miss Hattie Hall, who had preceded me over from Montag's, and another lady who introduced herself to me as Mrs. Arthur White, and the office boy; Mrs. Arthur White wanted to see her husband, and I went into the inner office, and took off my coat and hat, and removed the papers which I had brought back from Montag Brothers in the folder, and put the folder away. It was about this time that I heard the elevator motor start up and the circular saw in the carpenter shop, which is right next to it, running. I heard it saw through some boards, which I supposed was the work that Mr. Holloway had referred to. I separated the orders from the letters which required answers, and took the other material, the other printed matter that didn't need immediate attention. I put that in various trays, and I think it was about this time that I concluded I would look and see how far along the reports were, which I use in getting up my financial report every Saturday afternoon, and to my surprise I found that the sheet which contains the record of pencils packed for the week didn't include the report for Thursday, the day the fiscal week ends; Mr. Schiff evidently, in the stress of getting up, figuring out, and filling the envelopes for the payroll on Friday, instead of, as usual, on Friday and half the day Saturday, had evidently not had enough time. I told Alonzo Mann, the office boy, to call up Mr. Schiff, and find out when he was coming down, and Alonzo told me the answer came back over the telephone that Mr. Schiff would be right down, so I didn't pay any more attention to that part of the work, because I expected Mr. Schiff to come down any minute. It was about this time that Mrs. Emma Clark Freeman and Miss Corinthia Hall, two of the girls who worked on the fourth floor, came in, and asked permission to go upstairs and get Mrs. Freeman's coat, which I readily gave, and I told them at the same time to tell Arthur White that his wife was downstairs. A short time after they left my office, two gentlemen came in, one of them a Mr. Graham, and the other the father of a boy by the name of Earle Burdette; these two boys had gotten into some sort of trouble during the noon recess the day before, and were taken down to police headquarters, and of course didn't get their envelopes the night before, and I gave the required pay envelopes to the two fathers, and chatted with them at some length in reference to the trouble their boys had gotten into the day previous. But just before they left the office, Mrs. Emma Clark Freeman and Miss Corinthia Hall came into my office and asked permission to use the telephone, and they started to the telephone, during which time these two gentlemen left my office. But previous to that, when these two gentlemen came in, I had gotten Miss Hattie Hall in and dictated what mail I had to give her, and she went out and was typewriting the mail; before these girls finished the typewriting of these letters and brought them to my desk to read over and sign, which work I started. Miss Clark and Miss Hall left the office, as near as may be, at a quarter to twelve, and went out, and I started to work reading over the letters and signing the mail . . .

Miss Hall left my office on her way home at this time, and to the best of my information there were in the building Arthur White and Harry Denham and Arthur White's wife on the top floor. To the best of my knowledge, it must have been from ten to fifteen minutes after Miss Hall left my office, when this little girl, whom I afterwards found to be Mary Phagan, entered my office and asked for her pay envelope. I asked for her number and she told me; I went to the cash box and took her envelope out and handed it to her identifying the envelope by the number. She left my office and apparently had gotten as far as the door from my office leading to the outer office, when she evidently stopped and asked me if the metal had arrived, and I told her, no. She continued on her way out and I heard the sound of her footsteps as she went away. It was a few moments after she asked me this question that I had an impression of a female voice saying something; I don't know which way it came from; just passed away and I had that impression. This little girl had evidently worked in the metal department by her question and had been laid off owing to the fact that some metal that had been ordered had not arrived at the factory; hence, her question. I only recognized this little girl from having seen her around the plant and did not know her name, simply identifying her envelope from her having called her number to me.

She had left the plant hardly five minutes when Lemmie Quinn, the foreman of the plant, came in and told me that I could not keep him away from the factory, even though it was a holiday; at which I smiled and kept on working. He first asked me if Mr. Schiff had come down and I told him he had not and he turned around and left. I continued work until I finished this work and these requisitions and I looked at my watch and noticed that it was a quarter to one. I called my home up on the telephone, for I knew that my wife and my mother-in-law were going to the matinee and I wanted to know when they would have lunch. I got my house and Minola answered the phone and she answered me back that they would have lunch immediately and for me to come right on home. I then gathered my papers together and went upstairs to see the boys on the top floor. This must have been, since I had just looked at my watch, ten minutes to one. I noticed in the evidence of one of the witnesses, Mrs. Arthur White, she states it was twelve thirty-five that she passed by and saw me. That is possibly true; I have no recollection about it; perhaps her recollection is better than mine; I have no remembrance of it; however, I expect that is so. When I arrived upstairs I saw Arthur White and Harry Denham who had been working up there and Mr. White's wife. I asked them if they were ready to go and they staid they had enough work to keep them several hours. I noticed that they had laid out some work and I had to see what work they had done and were going to do. I asked Mr. White's wife if she was going or would stay there as I would be obliged to lock up the factory, and Mrs. White said, No, she would go then. I went down and gathered up my papers and locked my desk and went around and washed my hands and put on my hat and coat and locked the inner door to my office and locked the doors to the street and started to go home.

Now, gentlemen, to the best of my recollection from the time the whistle blew for twelve o'clock until a quarter to one when I went upstairs and spoke to Arthur White and Harry Denham, to the best of my recollection, I did not stir out of the inner office; but it is possible that in order to answer a call of nature or to urinate I may have gone to the toilet. Those are things that a man does unconsciously and can not tell how many times not when he does it. Now, sitting in my office at my desk, it is impossible for me to see out into the outer hall when the safe door is open, as it was that morning, and not only is it impossible for me to see out, but it is impossible for people to see in and see me there.

I continued on up Forsyth to Alabama and down Alabama to Whitehall where I waited a few minutes for a car, and after a few minutes a Georgia Avenue car came along; I took it and arrived home at about one twenty. When I arrived at home, I found that my wife and my mother-in-law were eating their dinner, and my father-in-law had just sat down and started his dinner. I sat down to dinner and before I had taken anything, I turned in my chair to the telephone, which is right behind me and called up my brother-in-law to tell him that on account of some work I had to do at the factory, I would be unable to go with him, he having invited me to go with him out to the ballgame. I succeeded in getting his residence and his cook answered the phone and told me that Mr. Ursenbach had not come back home. I told her to give him a message for me, that I would be unable to go with him. I turned around and continued eating my lunch, and after a few minutes my wife and mother-in-law finished their dinner and left and told me goodbye. My father-in-law and myself continued eating our dinner, Minola McKnight serving us. After finishing dinner, my father-in-law said he would go out in the back yard to look after his chickens and I lighted a cigarette and laid down. After a few minutes I got up and walked up Georgia Avenue to get a car. I missed the ten minutes to two car and I looked up and saw in front of Mr. Wolfsheimer's residence, Mrs. Mickle, an aunt of my wife who lives in Athens, and there were several ladies there and I went up there to see them and after a few minutes Mrs. Wolfsheimer came out of the house and I waited there until I saw that I could catch the car. I got on the car and talked to Mr. Loeb on the way to town. The car got to a point about the intersection of Washington Street and Hunter Street and the fire engine house and there was a couple of cars stalled up ahead of us, the cars were waiting there to see the memorial parade; they were all banked up. After it stood there a few minutes as I did not want to wait, I told Mr. Loeb that I was going to get out and go on as I had work to do. So I went on down Hunter Street, going in the direction of Whitehall and when I got down to the corner of Whitehall and Hunter, the parade had started to come around and I could not get around at all and I had to stay there fifteen or twenty minutes and see the parade.

Then I walked on down Whitehall on the side of Mr. M. Rich & Bros. Store towards Brown and Allens; when I got in front of M. Rich & Bros. store, I stood there between half past two and a few minutes to three o'clock until the parade passed entirely; then I crossed the street and went on down to Jacobs and went in and purchased twenty five cents worth of cigars. I then left the store and went on down Alabama Street to Forsyth Street and down Forsyth Street to the factory. I unlocked the street door and then unlocked the inner door and left it open and went on upstairs to tell the boys that I had come back and wanted to know if they were ready to go, and at that time they were preparing to leave. I went immediately down to my office and opened the safe and my desk and hung up my coat and hat and started to work on the financial report, which I will explain. Mr. Schiff had not come down and there was additional work for me to do.

In a few minutes after I started to work on the financial sheet, which I am going to take up in a few minutes, I heard the bell ring on the time clock outside and Arthur White and Harry Denham came into the office and Arthur White borrowed $2.00 from me in advance on his wages. I had gotten to work on the financial sheet, figuring it out, when I happened to go out to the lavatory and on returning to the office, the door pointed out directly in front, I noticed Newt Lee, the watchman, coming from towards the head of the stairs, coming towards me. I looked at the clock and told him the night before to come back at four o'clock for I expected to go to the baseball game. At that time Newt Lee came along and greeted me and offered me a banana out of a yellow bag which he carried, which I presume contained bananas; I declined the banana and told him that I had no way of letting him know sooner that I was to be there at work and that I had changed my mind about going to the ballgame. I told him that he could go if he wanted to or he could amuse himself in any way that he saw fit for an hour and a half, but to be sure and be back by half past six o'clock. He went off down the stair-case leading out and I returned to my office. Now, in reference to Newt Lee, the watchman, the first night he came there to watch, I personally took him around the plant, first, second, and third floors and into the basement, and told him that he would be required, that it was his duty, to go over that entire building every half hour; not only to completely tour the upper four floors but to go down to the basement; and I specially stressed the point that that dust bin along here was one of the most dangerous places for a fire and I wanted him to be sure and go back there every half hour and to be careful how he held his lantern. I told him it was a part of his duty to look after and lock that back door and he fully understood it, and I showed him the cut-off for the electric current and told him in case of fire that ought to be pulled so no fireman coming in would be electrocuted. I explained everything to him in detail and told him he was to make that tour every half hour and stamp it on the time card and that that included the basement of the building. . . . Now, on one of these slips, Newt Lee would register his punches Saturday night, and on Sunday night he would register his punches on the other. His punches on Monday night would be registered on two new slips that would be put into the clock on Monday night. As I was putting these time slips into the clock, as mentioned, I saw Newt Lee coming up the stairs, and looking at the clock, it was as near as may be six o'clock—looking straight at the clock; I finished putting the slip in and went back to wash up, and as I was washing, I heard Newt Lee ring the bell on the clock when he registered his first punch for the night, and he went downstairs to the front door to await my departure; after washing, I went downstairs—I put on my hat and coat—got my hat and top coat and went downstairs to the front door. As I opened the front door, I saw outside on the street, on the street side of the door, Newt Lee in conversation with Mr. J. M. Gantt, a man that I had let go from the office two weeks previous. They seemed to be in discussion, and Newt Lee told me that Mr. Gantt wanted to go back up into the factory, and he had refused his admission, because his instructions were for no one to go back into the factory after he went out, unless he got contrary instructions from Mr. Darley or myself. I spoke to Mr. Gantt, and asked him what he wanted, he said he had a couple of pairs of shoes, black pair and tan pair, in the shipping room. I told Newt Lee it would be all right to pass Gantt in and Gantt went in, Newt Lee closed the door, locking it after him—I heard the bolt turn in the door. I then walked up Forsyth Street to Alabama, down Alabama to Broad Street, where I posted the two letters, one to my uncle, Mr. M. Frank, and one to Mr. Pappenheimer, a few minutes after six, and continued on my way down to Jacobs Whitehall and Alabama Street store, where I went in and got a drink at the soda fount, and bought my wife a box of candy. I then caught the Georgia Avenue car and arrived home about six twenty-five. I sat looking at the paper until about six-thirty when I called up at the factory to find out if Mr. Gantt had left. I called up at six-thirty because I expected Newt Lee would be punching the clock on the half hour and would be near enough to the telephone to hear it and answer it at that time. I couldn't get Newt Lee then, so I sat in the hall reading until seven o'clock, when I again called the factory; this time I was successful in getting Newt Lee and asked him if Mr. Gantt had gone again; he said, "Yes," I asked if everything else was all right at the factory; it was, and then I hung up. . . .

The next day, Sunday, April 27th, I was awakened at something before seven o'clock, by the telephone ringing. I got out of bed—was tight asleep, it awakened me—but I got out of bed, put on a bathrobe and went down to answer the telephone, and a man's voice spoke to me over the phone and said—I after-wards found out this man that spoke to me was City Detective Starnes—said "Is this Mr. Frank, Superintendent of the National Pencil Company?" I said, "Yes, sir," he says, "I want you to come down to the factory right away," I says, "What's the trouble, has there been a fire?" He says, "No, a tragedy, I want you to come down right away," I says, "All right," he says, "I'll send an automobile for you," I says, "All right," and hung up and went upstairs to dress. I was in the midst of dressing to go with the people who should come for me in the automobile, when the automobile drove up, the bell rang, and my wife went downstairs to answer the door. She had on—just had a night dress with a robe over it. I followed my wife—I wasn't completely dressed at that time—didn't have any trousers and shirt on—I went downstairs— followed my wife in a minute or two. I asked them what the trouble was, and the man who I afterwards found out was Detective Black, hung his head and didn't say anything. Now, at this point, these two witnesses, Mr. Rogers and Mr. Black, differ with me on the place where the conversation occurred—I say, to the best of my recollection, it occurred right there in the house in front of my wife; they say it occurred just as I left the house, in the automobile; but be that as it may, this is the conversation: They asked me did I know Mary Phagan, I told them I didn't, they said to me, "Didn't a little girl with long hair hanging down her back come up to your office yesterday sometime for her money—a little girl who works in the tipping plant?" I says, "Yes, I do remember such a girl coming up to my office, that worked in the tipping room, but I didn't know her name was Mary Phagan." "Well, we want you to come down right away with us to the factory," and I finished dressing; and as they had said they would bring me right away back, I didn't have breakfast, but went right on with them in the automobile, made the trip to the undertaking establishment very quickly—I mean, they made the trip downtown very quickly, and stopped at the corner of Mitchell and Pryor Streets, told me they were going to take me to the undertaker's first, that they wanted me to see the body and see if I could identify the little girl. I went with them to the undertaking establishment and one of the two men asked the attendant to show us the way into where the body was, and the attendant went down a long dark passageway with Mr. Rogers following, then I came, and Black brought up the rear; we walked down this long passageway until we got to a place that was apparently the door to a small room—very dark in there, the attendant went on and suddenly switched on the electric light, and I saw the body of the little girl. Mr. Rogers walked in the room and stood to my right, inside of the room. I stood right in the door, leaning up against the right facing the door, and Mr. Black was to the left, leaning on the left facing, but a little to my rear, and the attendant, whose name I have since learned was Mr. Chessling, [sic] was on the opposite side of the little cooling table to where I stood—in other words, the table was between him and me; he re-moved the sheet which was covering the body, and took the head in his hands, turned it over, put his finger exactly where the wound in the left side back of the head was located—put his finger right on it; I noticed the hands and arms of the little girl were very dirty—blue and ground with dirt and cinders, the nostrils and mouth—the mouth being open—nostrils and mouth just full of sawdust and swollen, and there was a deep scratch over the left eye on the forehead; about the neck, there was twine—a piece of cord similar to that which is used at the pencil factory and also a piece of white rag. After looking at the body, I identified that little girl as the one that had been up shortly after noon the day previous and got her money from me. We then left the undertaking establishment, got in the automobile, and rode over to the pencil factory. Just as we arrived opposite the pencil factory, I saw Mr. Darley going into the front door of the pencil factory with another man, whose name I didn't know; we went up to the second floor, the office floor, I went into the inner office, hung up my hat, and in the inner office, I saw the night watchman, Newt Lee, in the custody of an officer, who I think was Detective Starnes—the man who had phoned me. I then unlocked the safe and took out the payroll book and found that it was true that a little girl by the name of Mary Phagan did work in the metal plant, and that she was due to draw $1.20, the payroll book showed that, and as the detective had told me that someone had identified the body of that little girl as that of Mary Phagan, there could be no question but that it was one and the same girl. The detectives told me then they wanted to take me down in the basement and show me exactly where the girl's body was found, and the other paraphernalia that they found strewed about; and I went to the elevator box—the switch box, so that I could turn on the current, and found it open. . . . However, I turned on the switch, started the motor, which runs the elevator, then Mr. Darley and half dozen more of us and the detectives got on the elevator; I got on the elevator and I started to pull the rope to start the elevator to going, and it seemed to be caught, and I couldn't move it, I couldn't move it with a straight pull, and couldn't get it loose, so I jumped out, we all got off, and I asked Mr. Darley to try his hand—he's a great deal larger man and a great deal stronger man than I was—so he was successful in getting it loose—it seemed like the chain which runs down in the basement had slipped a cog and gotten out of gear and needed somebody to force it back; however, Mr. Darley was successful in getting it loose, and it started up, and I got on and the detectives got on and I caught hold of the rope and it worked all right. In the basement, the officers showed us just about where the body was found, just beyond the partition of the Clark Woodenware Company, and in behind the door to the dust bin, they showed us where they found the hat and slipper on the trash pile, and they showed us where the back door, where the door to the rear was opened about eighteen inches. After looking about the basement, we all went upstairs and Mr. Darley and myself got some cords and some nails and hammer and went down the basement again to lock up the back door, so that we could seal the factory from the back, and nobody would enter. After returning upstairs, Mr. Darley and myself accompanied Chief Lanford on a tour of inspection through the three upper floors of the factory, to the second floor, to the third floor and to the fourth floor, we looked into each bin, and each partition, and each dressing room and looked into that very dressing room that has figured so prominently in this trial, and neither Mr. Darley nor myself noticed anything peculiar on that floor, nor did Sergeant Lanford, Chief of the Atlanta detectives, notice anything peculiar. . . . Now, gentlemen, I have heard a great deal, and have you, in this trial, about nervousness, about how nervous I was that morning. Gentlemen, I was nervous, I was completely unstrung, I will admit it; imagine, awakened out of my sound sleep, and a morning run down in the cool of the morning in an automobile driven at top speed, without any food or breakfast, rushing into a dark passageway, coming into a darkened room, and then suddenly an electric light flashed on, and to see that sight that was presented by that poor little child; why, it was a sight that was enough to drive a man to distraction; that was a sight that would have made a stone melt; and then it is suspicious, because a man who is ordinary flesh and blood should show signs of nervousness. Just imagine that little girl, in the first blush of young womanhood, had had her life so cruelly snuffed out, might a man not be nervous who looked at such a sight? Of course I was nervous; any man would be nervous if he was a man. We went with the officers in the automobile, Mr. Rogers was at the driving wheel, and Mr. Darley sat next to him, I sat on Mr. Darley's lap, and in the back was Newt Lee and two officers. We rode to headquarters very quickly and on arrival there Mr. Darley and I went up to Chief Lanford's office where I sat and talked and answered every one of their questions freely and frankly, and discussed the matter in general with them, trying to aid and to help them in any way that I could. It seemed that, that morning the notes were not readily accessible, or for some other reason I didn't get to see them, so I told them on leaving there that I would come back that afternoon, which I ultimately did; after staying there a few minutes, Mr. Darley and myself left, and inasmuch as Mr. Darley hadn't seen the body of the little girl, we went over to Bloomfield's on Pryor Street and Mitchell, and when we went into the establishment, they told us somebody was busy with the body at that time and we couldn't see it, and we started to leave, when we met a certain person with whom we made arrangements to watch the building, because Newt Lee was in custody at that time... .