Last Updated on July 25, 2024 by Mary Phagan

The dream was always the same. The funnel-shaped cloud was the largest I had seen, and it was heading directly for me and those I love. Miraculously, my brother Michael found a cave in which we could be safe. The cloud destroyed everything in its path, but those in the cave remained safe. Screaming and sweating, I would awaken with my heart palpitating—and then realize that it was only a dream. But I became afraid to sleep for fear that the dream would come back. And it did. Again and again.

The story of little Mary Phagan had indeed followed me to Florida.

A history professor asked me, "Are you, by any chance, related to little Mary Phagan?" Then several classmates quizzed me about the story.

I decided that I had to know the answers to the questions that haunted me. I just had to know. I couldn't be Mary Phagan without this shadow of my past. It was my history, my legacy. And I had to answer those questions.

I became friends with Amy. Amy was Jewish, and, as with all friends, religion came up between us. Amy and I exchanged our beliefs and answered the "why's" of our faiths. There were no barriers between us. Once a group of us were talking, and someone asked me in front of Amy that question: "Are you, by any chance, related to little Mary Phagan?"

"Yes," I replied. "Wasn't Leo Frank a Jewish man?" she persisted.

I told her "yes," again. But Amy never mentioned the story of little Mary Phagan, and I never told her. I never felt obliged to tell her more; it didn't have anything to do with our friendship. We were best friends[even to this day]and that was that.

My family delighted in my friendship with Amy and her family. During one Christmas vacation my dad related to me how he had become part of a Jewish family. For the first time I realized why I had always called this particular couple Grandma and Grandpa—and still do.

It happened around Christmastime in 1952. My Dad had just been promoted to Staff Sergeant and was flying out of the Larson Air Force Base in Moses Lake, Washington.

"As Christmas approached, we geared up to make flights back east to provide transportation for all the Military Services," he explained. "Plans were made that each flight would make certain strategic stops to drop off troops and pick them up after Christmas and bring them back to Larson Air Force Base. On December 20, 1952, there was a fatal crash that took the lives of about eighty-seven young military men. It was the worst military air disaster in history.

"Airplane crashes are terrible in more ways than one: they create havoc in the loss of lives and materials, and they put men to a test that they cannot survive. The dead men must be escorted home for burial. The escorts are called Color Guards. They are hand-picked as a rule, versed in the nature of life at its worst. Each family that has lost a loved one will have a thousand questions to ask the Color Guard. He will have no answers and must rely on his own ability to handle the situation. And no two will be the same. Some Color Guards will break under the pressure, particularly if they were friends. One of the crew members on the flight was my close friend, Robert Jacobs. He was a radio operator whose position was on the flight deck with the pilot, co-pilot, navigator, and flight engineer. All of these crew members perished in that crash. I knew them all. Tears still come to my eyes when I think about it and how many lives it claimed.

"Brigadier General H.W. Bowman, commander of the 62nd Troop Carrier Wing (H), and Lt. Colonel Roland K. McCoskrie, commander of 7th Troop Carrier Squadron, suffered only as commanders can suffer when they lose men in a tragic accident.

"As in any accident, the clean up crew was mostly volunteers; these men are true heroes. At times some even risk their lives in trying to save others. It took over three days just to recover all the bodies. And then there was the horrible task of identifying some of the bodies. Preparations and transportation arrangements were made, and then came the selection of the Color Guards. There was no Jewish man to escort our radio operator. One would have to be selected from another squadron, someone who did not even know his name, unless someone in our squadron would step forward to be his Color Guard. With head held high, tears in my eyes, my heart about to burst, I took that step forward. I could not allow a stranger to escort my friend and fellow crew member home to his parents. In my mind, that would hurt them even more.

"I felt that I would break under that pressure when I presented the American flag to Mr. and Mrs. Jacobs at the gravesite. I did! When I presented the flag to them, I could hardly talk for the tears rolling down my cheeks: 'This flag is presented to you by a grateful nation in remembrance of your loved one.' For one moment, time stood still for three broken hearts, the parents and mine became one in grief. They invited me home to say the Kaddish, a memorial prayer, for their son. I became an adopted 'son,' and to this day I call them Mom and Dad and you children call them Grandma and Grandpa. Every Mother's Day, I send flowers to my friend's mother. She's a very special person.

"They asked me questions I had no answers for, except the simple truths and personal knowledge that I had of their son. Of course they wanted to know 'why.' I explained that their son was one of the best and the best always are selected for the tough flights. I don't think that I would have the guts to do that job again. I was to receive four letters of appreciation and commendation: one from the Jewish War Veterans of the U.S.; one from Brigadier General H.W. Bowman, Commanding General 62nd Troop Carrier Wing (H); one from Colonel Richard Jones, Commanding Officer 62nd Troop Carrier Group (H); and one from Lt. Colonel Roland K. McCoskrie, Commanding Officer 7th Troop Carrier Squadron (H). These letters are still in my personal folders today.

"Life takes a pause and then continues on!"

J

After two years at Flagler, both Amy and I felt that it wasn't offering the programs that we needed for our careers. We both transferred to Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida, during the summer of 1974.

I worked hard, and in August of 1977, I received my Master of Science in the College of Education Program at Florida State University with honors. And what was even more exciting was I already had a job: I was to be the Consultant/Itinerant Teacher for the Visually Impaired for the Griffin Cooperative Educational Service in Griffin, Georgia. I would be going back home.

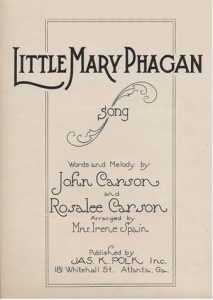

I began at the agency the first week of September. I was introduced to the various superintendents of the systems in which I would be responsible for setting up the vision program. Several of the superintendents asked me that question: "Are you, by any chance, related to little Mary Phagan?" One of them privately called me in his office and sang me "The Ballad of Mary Phagan" by Fiddling John Carson of Blue Ridge, Georgia:

Little Mary Phagan went to town one day,

And went to the pencil factory

to see the big parade.

She left her home at eleven,

And kissed her mother goodbye,

Not one time did the poor child think

that she was going to die.

Leo Frank met her, with a brutal heart we know,

He smiled and said, "Little Mary,

Now you will go home no more."

He sneaked along behind her,

Till she reached the metal room,

He laughed and said, "Little Mary,

you have met your fatal doom."

She fell upon her knees, and to

Leo Frank she pled,

He took his stick from the trash pile

And hit her across the head.

The tears rolled down her rosy cheeks,

While the blood flowed down her back,

But still she remembered telling her mother

What time she would be back.

He killed little Mary Phagan--

it was on a holiday--

And he called on Jim Conley to take her body away.

He took her to the basement,

She was bound hand and feet,

And down in the basement little Mary

lay asleep.

Newt Lee was the watchmen—

when he went to wind his key,

Down in the basement,

little Mary he could see.

He called for the officers—their

names I do not know.

They came to the pencil factory

Says "Newt Lee, you must go."

They took him to the jailhouse,

They locked him in a cell,

But the poor innocent negro

Knew nothing for to tell.

I have a notion in my head that

when Frank comes to die,

And stands the examination in

the courthouse in the skies,

He will be astonished at the questions

The angels are going to say

of how he killed little Mary on one holiday.

Come all you good people

wherever you may be,

And supposing little Mary

belonged to you or me.

Her mother sat a weeping—she

weeps and mourns all day—

She prays to meet her darling in a

better world some day.

Little Mary is in Heaven, while

Leo Frank is in jail,

Waiting for the day to come when

he can tell his tale.

Judge Roan passed the sentence

And you bet he passed it well;

Solicitor Hugh M. Dorsey

sent Leo Frank to hell.

Now, God Bless her mother.

He told me that his mother had sung the ballad throughout his childhood. He had never forgotten a word. While he was singing the ballad, I realized that little Mary Phagan was me too—not a separate entity—and I could not evade our relationship. Nor did I want to.

I was ready to search for answers to those haunting questions. Now I had to know if what my father taught me was accurate and factual. I began extensive research. I looked again at the Brief of Evidence, reference books, and the newspaper accounts in a different way, a critical way. I read everything I could find on the economic, political, social and psychological climate of the South in 1913.

By the time little Mary Phagan was murdered, the Civil War had been over only forty-eight years. Today, other parts of the country accuse Southerners of "still fighting the Civil War." To an extent that is true. It was true to an even greater extent in 1913.

The focus of Southern society was tradition—which also meant opposition to change. And the commitment to tradition was often manifested in a loyalty on the part of Southerners to "their own kind" which usually resulted in a paranoid suspicion of outsiders.

Another strong part of this tradition is the esteem in which white women, and particularly young white girls, are held. Southerners have always had a fear— whatever its origins—of assaults upon women.

The industrialization which began in the last part of the nineteenth century centered on the cities, and it was in the rural areas that the commitment to tradition held most strongly. But life in rural areas was difficult—very difficult for most of the poorer people. So, they emigrated to urban areas.

Apparently, life wasn't much better in the cities, although the opportunities to make money were far greater, and it was especially dreary in Atlanta. Those who came in from the country to find work in the mills and factories were white tenant farmers and they lived for the most part in the bleak factory slums which surrounded Atlanta's industrial sections. Just as Grand-mother Fannie Phagan Coleman was preparing to move her fatherless children from Alabama back to Atlanta/ Marietta around 1908 or 1909, about a third of Atlanta's population had no water mains or sewers. Two years before little Mary Phagan was slain, between fifty and seventy-five percent of the schoolchildren of Atlanta suffered from anemia, malnutrition, and heart disease. In 1906, 22,000 out of a population of 115,000 were held by the police for disorderly conduct or drunkenness. That year, one of the worst race riots in memory broke out in Atlanta, and the newspapers seized upon stories—true or not—of Negro assaults on white women.

Wages were low in the mills and factories and the normal workday began at 6:00 a.m. and ended at 6:00 p.m. Mary Phagan had earned only ten cents an hour at the National Pencil Company. Children were exploited—especially in the cotton mills. I thought of my father's description of his mother Mary Richards Phagan, whom the factory bosses would hide from the labor inspectors.

It was probably inevitable that family and community ties, another bulwark of tradition, began to weaken, despite people's struggles to hold onto them, and they grew increasingly resentful of those whom they considered to be their exploiters.

I realized, as my research began to clarify a lot of things for me, that little Mary Phagan, white, pretty, well-liked, just short of fourteen, a laborer in a factory or "sweat shop," came to stand for what was good, pure, sweet and exploited about the South. And that Leo Frank, a Northerner, a Jew, superintendent, part owner of the factory, and well-to-do, would have fit perfectly the idea of the outsider which Southerners traditionally held in such suspicion and the exploiter of whom they were growing increasingly resentful. The entire family believed that he killed Mary Phagan. So did I.

On April 28, 1913, Leo Frank sent a telegram to Adolph Montag in New York: Atlanta, Ga. Apr. 28, 1913 Mr. Adolph Montag, c/o Imperial Hotel, New York. You may have read in Atlanta papers of factory girl found dead Sunday morning in cellar of pencil factory. Police will eventually solve it. Assure my uncle I am all right in case he asks. Our company has case well in hand. On April 29, 1913, three days after little Mary Phagan's body was discovered, the Atlanta Georgian reported that four suspects were being held. The headline read: "IS THE GUILTY MAN AMONG THOSE HELD?" These men were:

1. A black night watchman, who is thought to know much more about the crime than he has told, but who has not been regarded as the perpetrator.

2. A former streetcar conductor for whom a strong alibi has never been established, and from whom suspicion is shifting.

3. A black elevator boy, who has never been held as a material witness, but against whom no evidence has been obtained.

4. A former employee of the National Pencil Company was located at the Plant Saturday and identified as being the "man with a little girl on Saturday night."

In neither the conductor's nor the elevator boy's case do police place much dependence on the so-called identifications. All of these men were cleared. At that time, neither Leo Frank, the factory superintendent, nor Jim Conley, the pencil factory janitor, appeared on the list. Leo Frank was at police headquarters that day but police were quoted as saying, "Frank is not under arrest," but that "he was under police guard for his own personal safety," and that "there are no charges against him." What led to the eventual arrest of Leo Frank, the factory superintendent? When Newt Lee, the night watchman who discovered the body of little Mary Phagan, was questioned by the police, he stated that he had been at the factory on April 26, 1913, and that when he began working at the pencil factory, Mr. Frank had told him to report at 6:00 p.m. on weekdays and at 5:00 p.m. on Saturdays. He said that, on Friday, the 25th of April, Leo Frank told him, "Tomorrow is a holiday and I want you to come back at four o'clock. I want to get off a little earlier than I have been getting off." Frank had plans to go to the baseball game with his brother-in-law. The game started at 4:00 p.m. Newt Lee said that he arrived at the factory at about three or four minutes before four. He then told the detectives: The front door was not locked. I pushed it open, went on in and got to the double door there. I was paid off Friday night at six o'clock. It was put out that everybody would be paid off then. Every Saturday when I get off, he gives me the keys at twelve o'clock, so that if he happened to be gone when I get back there at five or six o'clock, I could get in, and every Monday morning I return the keys to him. The front door had always been unlocked on previous Saturday afternoons. After you go inside and come up about middle ways of the steps, there are some double doors there. It was locked on Saturday when I got there. Have never found it that way before. I took my key and unlocked it. When I went upstairs, I had a sack of bananas and I stood to the left of that desk like I do every Saturday. I says like I always do "Alright Mr. Frank" and he come bustling out of his office. He had never done that before. He always called me when he wanted to tell me anything and said, "Step here a minute, Newt." This time he came up rubbing his hands and says, "Newt, I am sorry that I had you come so soon, you could have been at home sleeping, I tell you what you do, you go out in town and have a good time." He had never let me off before that. I could have laid down in the shipping room and gone to sleep, and I told him that. He says, "You needs to have a good time. You go downtown, stay an hour and a half, and come back your usual time at six o'clock." I then went out the door and stayed until about four minutes to six. When I came back the doors were unlocked just as I left them and I went and says, "Alright, Mr. Frank," and he says, "What time is it?" and I says, "It lacks two minutes of six." He says, "Don't punch yet, there is a few worked today, and I want to change the slip." It took him twice as long this time than it did the other times I saw him fix it. He fumbled putting it in, while I held the lever for him and I think he made some remark about he was not used to putting it in. When Mr. Frank put the tape in I punched and I went downstairs. While I was down there Mr. Gantt came from across the street from the beer saloon and says, "Newt, I got a pair of old shoes that I want to get upstairs to have fixed." I says, "I ain't allowed to let anybody in here after six o'clock." About that time Mr. Frank come bustling out of the door and run into Gantt unexpected and he jumped back frightened. Gantt says, "I got a pair of old shoes upstairs, have you any objection to my getting them?" Frank says, "I don't think they are up there, I think I saw the boy sweep some up in the trash the other day." Mr. Gantt asked him what sort they were and Mr. Frank says "tans." Gantt says, "Well, I had a pair of black ones too." Frank says, "Well, I don't know," and he dropped his head down just so. Then he raised his head and says, "Newt, go with him and stay with him and help him find them" and I went up there with Mr. Gantt and found them in the shipping room, two pair, the tans and the black ones. Mr. Frank phoned me that night about an hour after he left, it was sometime after seven o'clock. He says, "How is everything?" and I says, "Everything is all right so far as I know," and he says "Goodbye." There is a light on the street floor just after you get in the entrance to the building. The light is right up here where that partition comes across. Mr. Frank told me when I first went there, "Keep that light burning bright, so the officers can see in when they pass by." It wasn't burning that day at all. I lit it at six o'clock myself. On Saturday I always lit it, but weekdays it would always be lit when I got there. On Saturdays I always got there at five o'clock. This Saturday he got me there an hour earlier and let me off later. There is a light in the basement down there at the foot of the ladder. He told me to keep that burning all the time. It has two little chains to it to turn on and turn off the gas. When I got there on making my rounds at seven o'clock on the 26th of April, it was burning just as low as you could turn it, like a lightning bug. I left it Saturday morning burning bright. I made my rounds regularly every half hour Saturday night. I punched on the hour and punched on the half and I made all my punches. The elevator doors on the street floor and office floor were closed when I got there on Saturday. They were fastened down just like we fasten them down every other night. When three o'clock came I went down the basement and when I went down and got ready to come back I discovered the body there. I went down to the toilet and when I got through I looked at the dust bin back to the door to see how the door was and it being dark I picked up my lantern and went there and I saw something laying there which I thought some of the boys had put there to scare me, then I got out of there. I got up the ladder and called up the police station. It was after three o'clock . . . I tried to get Mr. Frank on the telephone and was still trying ... I guess I was trying about eight minutes. L. S. Dobbs, Sergeant of Police, and J. N. Starnes, City Officer, went to the National Pencil Factory after receiving the call from Newt Lee. They discovered the notes under the sawdust, a hat without ribbons on it, paper and pencils, and a shoe near the boiler; a bloody handkerchief about ten feet further from the body towards the rear on a sawdust pile. While Dobbs was reading the notes—"A tall black negro did this, he will try to lay it on the night"—when he said the word "night," Lee said, "That means the night watchman." J. N. Starnes finally reached Frank by telephone around 6:30 a.m. and sent Boots (W.W.) Rogers with John R. Black after him. The earlier calls made by Lee and the police had not been answered. Boots Rogers and Mr. Black said they found Frank extremely nervous and that he asked to eat his breakfast before leaving—a request the police denied him. Frank also denied knowledge of a little girl named Mary Phagan.

They then took Frank to the morgue. They stated that he scarcely looked at the body and would not enter the room where it lay. He continued to be agitated and nervous. Upon arriving at the factory, he consulted his time book and reported, "Yes, Mary Phagan worked here, and she was here yesterday to get her pay." He then told the police, "I will tell you about the exact time she left here. My stenographer left about twelve o'clock, and a few minutes after she left, the office boy left, and Mary came in and got her money and left." Further questioning revealed that Frank maintained he was inside his office "every minute" from noon to 12:30. On Sunday, he confirmed to the police that the time slips punched by Newt Lee were correct, but the next day he said the time slips contained errors. Frank appeared at police headquarters on Monday morning with his attorneys Luther Z. Rosser and Herbert Haas, who evidently had been contacted on Sunday.

Frank advised police that Newt Lee and J. M. Gantt had been at the factory and that Gantt "knew Mary Phagan very well." This led to their arrests. On Monday morning, April 28, when the factory opened, R. P. Barrett, a machinist, reported that he found blood spots near a machine at the west end of the dressing room on the second floor which had not been there Friday. Hair was also found on the handle of a bench lathe and strands of cords of the type that were used to strangle Mary Phagan were hung near the dressing room. Leo Frank was arrested on Tuesday, April 29, and incarcerated in the Fulton Tower. The police said his hands were quivering and that he was pale. He again reported that Mary Phagan came in "between 12:05 and 12:10, maybe 12:07, to get her pay envelope, her salary." He stated, "I paid her and she went out of the office." Later that evening Frank had a conversation with Newt Lee, who was handcuffed to a chair. Newt Lee reported that when Frank came in, he dropped his head and looked down. They were all alone and Lee said, "Mr. Frank, it's mighty hard for me to be handcuffed here for something I don't know anything about." Frank said, "That's the difference, they have got me locked up and a man guarding me." Lee then asked, "Mr. Frank, do you believe I committed that crime," and he said, "No, Newt, I know you didn't, but I believe you know something about it." Lee then said, "Mr. Frank, I don't know a thing about it, no more than finding the body." Frank said, "We are not talking about that now, we will let that go. If you keep that up we will both go to hell." The police had also learned that Frank refused to send Mary Phagan's pay home with Helen Ferguson, a friend. Then, not too long after Leo Frank's indictment and Jim Conley's statements, the police also obtained a statement from Minola McKnight, the black cook in the Frank home. She reported that when Frank came home that Saturday, he was drunk, talked wildly, and threatened to kill himself, thus forcing his wife to sleep on the floor. Minola's sworn statement was witnessed by her lawyer, George Gordon. Yet, three days later Mrs. McKnight publicly repudiated her affidavit, claiming that she had signed it to obtain release from the police. It seems that while her original statement made the front page of the newspapers, her repudiation was printed unobtrusively on an inside page. Other questions nagged at me. My family maintained that Mary Phagan had been violated. What did the medical evidence disclose? Was the blood found on her legs and underwear the result of rape or menstrual blood? Was undisputable evidence of rape found?

According to my great-grandmother, “Mary had not reached puberty even though she was large and well formed, appearing to be sixteen years of age.” . [Footnote 5] Mary did not have a menstrual cycle as she did not reach the age of complete puberty. If Mary was on her menstrual cycle, some indication of personal hygiene such as a menstrual cloth attached with pins would have been found on her body.

Brief of Evidence, 1913

The Brief of Evidence testimony of Dr. H. F. Harris, Sworn for the State state that he made an examination on May 5, 1913 (Autopsy Report) stated he made a” microscopic examination of the vagina and uterus. Natural menses would cause an enlargement of the uterus, but not of the vagina. In my opinion the menses could not have caused any dilation of the blood vessels and discoloration of the walls. Dr. Harris also stated that the “violence to the private parts might have been produced by the finger or by other means, but I found evidence of violence. It takes a rather considerable knock to tear epithelium off to the extent that bleeding would occur. I found the epithelium completely detached in places and in other places it was not detached. A digital examination means putting the finger in. The swelling and dilation of the blood vessels can only be seen by a microscope. It is impossible to say how much they were swollen.”

The examination included the privates of Mary Phagan: “I found no spermatozoa. On the walls of the vagina there was evidences of violence of some kind. The epithelium was pulled loose, completely detached in places, blood vessels were dilated immediately beneath the surface and a great deal of hemorrhage in the surrounding tissues. The dilation of the blood vessels indicated to me that the

injury had been made in the vagina some little time before death. Perhaps ten to fifteen minutes. It had occurred before death by reason of the fact that these blood vessels were dilated. Inflammation had set in and it takes an appreciable length of time for the process of inflammatory change to begin.

There was evidence of violence in the neighborhood of the hymen.”

Governor John M. Slaton chose to ignore the autopsy report in his Commutation (Chapter 7) and reported findings of "Dr. Hurt who declared there was no violence to the parts and the blood was characteristic of mensural flow. There were no external signs of rape. The body was not mutilated, thereon being on the head and scratches on the elbow, and a wound about two inches below the knee."

The autopsy report as well as the Brief of Evidence show that Mary Phagan’s blood was not her menses and she was raped/sexually assaulted.

DR. H. F. HARRIS, Sworn for the State, August, 1913.

I am a practicing Physician. I made an examination of the body of Mary Phagan on May 5th [1913].

[Skull and Head]

On removing the skull I found there was no actual break of the skull, but a little hemorrhage under the skull, corresponding to point where blow had been delivered, which shows that the blow was hard enough to have made the person unconscious. This wound on the head was not sufficient to have caused death.

[Strangulation]

I think beyond any question she came to her death from strangulation, from this cord being wound around her neck.

[Left Fist Punches the Victims Right Eye]

The bruise around the [right] eye was caused by a soft instrument, because it didn’t show the degree of contusion that would have been produced by a hard instrument. The outside cuticle of the skin wasn’t broken. The injury to the [right] eye and scalp were caused before death.

[Stomach]

I examined the contents of the stomach, finding 160 cubic centimeters of cabbage and biscuit, or wheaten bread. It had progressed very slightly towards digestion. It is impossible for one to say absolutely how long this cabbage had been in the stomach, but I feel confident that she was either killed or received the blow on the back of the head [From the solid iron handle of the bench lathe found in the metal room] within a half hour after she finished her meal [(According to Mrs. Coleman, 11:30 a.m. is when Mary Phagan ate her last meal)]. I have some cabbage here from two normal persons. Here was same meal taken of cabbage and wheaten bread by two men of normal stomach, and contents taken out within an hour. We found there was very little cabbage left.

[Genitals]

I made an examination of the privates of Mary Phagan. I found no spermatozoa. On the walls of the vagina there was evidences of violence of some kind. The epithelium was pulled loose, completely detached in places, blood vessels were dilated immediately beneath the surface and a great deal of hemorrhage in the surrounding tissues. The dilation of the blood vessels indicated to me that the injury had been made in the vagina some little time before death. Perhaps ten to fifteen minutes. It had occurred before death by reason of the fact that these blood vessels were dilated. Inflammation had set in and it takes an appreciable length of time for the process of inflammatory change to begin. There was evidence of violence in the neighborhood of the hymen.

[Rigor Mortis]

Rigor mortis varies so much that it is not accurate to state how long after death it sets in. It may begin in a few minutes and may be delayed for hours.

[Estimated Range for Time of Death Based on 11:30 a.m. Meal Digestion: Twelve Noon to 12:15 p.m. on Saturday April 26, 1913]

I could not state from the examination how long Mary Phagan was dying. It is my opinion that she lived from a half [noon] to three-quarters of an hour [12:15 p.m.] after she ate her [brunch] meal [at 11:30 a.m. according to Mrs. Coleman, Mary’s biological mother who testified she served her daughter a meal, before she left].

[Sexual Violence: Rape]

The evidence of violence in the vagina had evidently been done just before death.

[Forensics of Strangulation]

The fact that the child was strangled to death was indicated by the lividity, the blueness of the parts, the congestion of the tongue and mouth and the blueness of the hands and fingernails.

[Lungs]

The lungs had the peculiar appearance which is always produced after embalming when formaldehyde is used. I am of the opinion that the wound on the back of the head could not have been produced by this stick (referring to: Defendant’s Exhibit 48, Leo Frank Trial Brief of Evidence, 1913).

[(Exhibit 48 was a bloody stick planted on the first floor of the National Pencil Company factory, by associates of the Leo Frank legal defense team, nearly three weeks (20 days) after the crime, and discovered by Detective McWorth of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. The significance of the bloody stick planted in the lobby, was that 3 weeks after the murder, other evidence like a pay envelop was put at the lobby where Conley had sat on Saturday, April 26, 1913. The stick was another failed effort to develop forensic evidence that Phagan was assaulted by Jim Conley in the lobby, when she walked down the stairs from the second floor, this planted evidence was in contradiction to all the forensic evidence suggesting Leo Frank murdered Mary Phagan in the metal room at the rear of the second floor. The stick was discovered by Detective McWorth around May 15th, 1913. Detective McWorth was relieved of his services in the Mary Phagan murder investigation after he kept on discovering planted evidence in the lobby of the National Pencil Company, three weeks after Atlanta Police had meticulously searched the building for clews.)]

[Microscope Analysis to Determine if Menstruation Could have Caused the Evidence of Violence to the Vagina]

I made a microscopic examination of the vagina and uterus. Natural menses would cause an enlargement of the uterus, but not of the vagina. In my opinion the menses could not have caused any dilation of the blood vessels and discoloration of the walls.

[Stomach and Digestion Analysis]

From my own experiments I find that the behavior of the stomach after taking a small meal of cabbage and bread is practically the same as taking some biscuit and water alone. I examined Mary Phagan’s stomach. It was normal in size, normal in position, and normal in every particular.

I made a microscopic examination of the contents in Mary Phagan’s case. It showed plainly that it had not begun to dissolve, or only to a very slight degree, and indicated that the process of digestion had not gone on to any extent at the time that this girl was rendered unconscious. I found that the starch she had eaten had undergone practically no alteration. The contents taken from the little girl’s stomach was examined chemically and the result showed that there were only slight traces of the first action of the digestive juices on the starch. It was plainly evident that none of the material had gone into the small intestines. As soon as food is put in the stomach the beginning of the secretion of the hydrochloric acid is found.

It is from the quantity of this acid that the stomach secretes that doctors judge the state and degree of digestion. In this case the acid had not been secreted in such an excess that any of it had become what we call free. In this case the amount of acid in this girl’s stomach was combined and was 32 degrees. Ordinarily in a normal stomach at the end of an hour it runs from 50 to 70 or 80. I found none of the pancreatic juices in the stomach which are usually found, about an hour after digestion starts.

CROSS EXAMINATION BY DEFENSE:

I don’t remember when Mr. Dorsey first talked to me about making this autopsy. As long as the heart was beating you could have put a piece of rope around the neck of this little girl and produced the same results as I found. I took about five or six ounces altogether out of the stomach. It was all used up in making my experiments. I know of no experiments made as to the effect of gastric juices where the patient is dead. The juices of the body after death gradually evaporate. The chemical analysis of each cabbage varies, not only in the plant but from the way it is cooked. It is a very vague matter as to what influences may retard digestion. Every individual is almost a law unto himself. To a certain extent different vegetables affect different stomachs different ways, but the average normal stomach digests anything that is eaten within reason. Some authorities claim that exercise will retard digestion. I don’t know that mental activity would have very much effect in retarding the digestion.

It is the generally accepted opinion that food begins to pass out of the stomach through the pyloris in about a half an hour. A great many things pass out of the stomach that are not digested. The juices of the stomach make no change in them. The stomach does not emulsify a solid. I never knew a normal man who could digest a solid. The science of digestion is rather a modern thing. I did not call in any chemist in making this examination. I said it was impossible for any one to say absolutely how long the cabbage had been in the stomach of Mary Phagan before she met her death, not within a minute or five minutes, but I say it was somewhere between one-half an hour and three-quarters. I am certain of that. Of course, if digestion had been delayed this time element would

change.

[Penis, Finger or Object?]

The violence to the private parts might have been produced by the finger or by other means, but I found evidence of violence. It takes a rather considerable knock to tear epithelium off to the extent that bleeding would occur. I found the epithelium completely detached in places and in other places it was not detached. A digital examination means putting the finger in. The swelling and dilation of the blood vessels could be seen only with a microscope. It is impossible to say how much they were swollen.

A scalp wound is very prone to bleed.

-End of Witness Testimony Concerning the Mary Phagan Autopsy, Leo Frank Trial Brief of Evidence, 1913

Testimony of Dr. Harris:

Startling Statements Made During Testimony of Dr. Harris

Atlanta Constitution

August 2nd, 1913

Making the startling declaration that Mary Phagan had been killed within thirty or forty-five minutes after she had eaten dinner, Dr. Roy F. Harris, state chemist, took the stand during the afternoon session yesterday.

It was Dr. Harris who made the autopsy upon the body when it was disinterred in Marietta on May 5. He brought with him into court specimens of predigested cabbage which had been removed from the slain girl’s stomach.

He also testified to the effect that the girl had suffered violence before death and recited the condition in which he had found blood vessels and tissues of the girl’s organs.

He was questioned first by Solicitor Dorsey.

“What is your occupation?”

“I am a physician.”

“How long have you been a physician?”

“Since 1889.”

“Give the jury a brief history of your career.”

“I was graduated in Atlanta in 1839 and in Philadelphia in 1890. I was professor of chemistry in the medical college at Philadelphia, and later became assistant professor of bacteriology in the Jefferson Medical college. I was professor in the Atlanta College of Medicine, and have been director of laboratory in the state board of health since the inauguration of the board.”

“Did you examine the body of Mary Phagan?”

“Yes. On May 5.”

“What did you discover, if anything?”

“Several discolorations. One was on the forehead, one on an arm and one on each of the left and right legs. A huge discoloration was on the right eye.”

“What did the discoloration of the right eye seem to have been inflicted by?”

“By a fist.”

“Was there another wound?”

“Yes. One on the head about an inch and a half in length. On removing the skull I found no break, but discovered signs of hemorrhage beneath—a hemorrhage which would have rendered the victim unconscious.”

Death Caused by Strangulation.

“What was the cause of death?”

“There was a ridge in the throat apparently made by a stout cord. It was very deep. Strangulation, beyond a doubt, was the cause.”

“Why do you say, doctor, that a fist caused the discoloration of the eye?”

“Because the discoloration was swollen and didn’t show any degree of contusion that an instrument or hard substance would have caused.”

“Do you think that this and the other injuries were made before death?”

“Unquestionably.”

“What did you find in her stomach upon its removal?”

“One hundred and sixty-six cubic centimeters of cabbage and biscuits.”

“Was this substance digested?”

“No.”

Here the witness took from his satchel a small vial containing fluid preservative, in which floated a small amount of cabbage.

“This,” he said, “is some of what I removed from the stomach.”

“How long was this substance in her stomach before death?”

“She was either killed or received the blow upon the head thirty or forty-five minutes after her last meal.”

Evidences of Violence.

Dr. Harris then testified that in examining the organs of the girl’s body he had discovered evidences of violence.

“How long does it take a corpse to begin rigor-mortis?”

“It varies so much in different cases that it is impossible to determine.”

“Are you able to say how long it was before Mary Phagan died?”

“No. I can’t say.”

“How long did she live after eating her last meal?”

“Thirty or forty-five minutes.”

“How much blood did she lose?”

“That, I cannot say.”

It was upon this last answer that Dr. Harris suffered the collapse. He was assisted from the stand by Deputy Sheriff Plennie Miner before the defense was able to being its cross-examination.

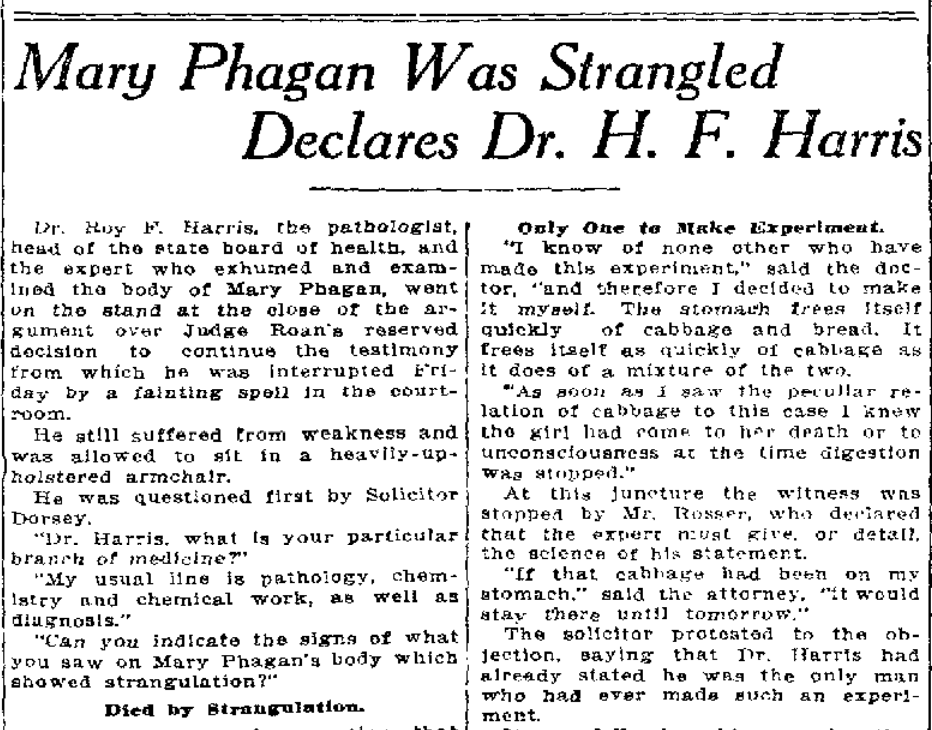

Mary Phagan Was Strangled Declares Dr. H. F. Harris

Atlanta Constitution

August 7th, 1913

Dr. Roy F. Harris, the pathologist, head of the state board of health, and the expert who exhumed and examined the body of Mary Phagan, went on the stand at the close of the argument over Judge Roan’s reserved decision to continue the testimony from which he was interrupted Friday by a fainting spell in the courtroom.

He still suffered from weakness and was allowed to sit in a heavily-upholstered armchair.

He was questioned first by Solicitor Dorsey.

“Dr. Harris, what is your particular branch of medicine?”

“My usual line is pathology, chemistry and chemical work, as well as diagnosis.”

“Can you indicate the signs of what you saw on Mary Phagan’s body which showed strangulation?”

Died by Strangulation.

“It was out of the question that her death was caused by a blow on the head—it was not sufficient to even produce noticeable pressure. The only thing evident from which death could have resulted was the deep indentation along the throat, obviously inflicted during life. There were other signs as well—the protruding tongue, congested blood in the face and hands, all of which indicated that strangulation had caused death.”

“Did you notice the larynx?”

“Yes; there seemed no damage done.”

“Did you see the windpipe?”

“Yes.”

“Did you take it out?”

“No; there seemed but little damage to it. I did not remove it because I did not want to mutilate the poor child any more than necessary.”

“Did you see the lungs?”

“Yes, but the lungs were congested, due to the use of formaldehyde used in embalming.”

The solicitor asked the defense for the bloody stick found by Pinkertons on May 10 in the pencil factory. It was produced and shown to the physician.

“Do you think the blow you found on the child’s head could have been inflicted by a cudgel like this?”

“In my opinion, I would think not—the gash evidently was inflicted with some sharp instrument.”

“Did you make a scientific examination of the female organs?”

Violence Before Death.

“Yes; I made a microscopic examination.”

Dr. Harris at this point testified as to the condition of the organs of the girl to show that violence of some sort had been done her.

Following these questions Dr. Harris was asked regarding certain experiments he had made on digestive organs relative to their action upon cabbage. He had started to detail a test he had made twelve years ago, when Rosser objected to his personal experience being put before the jury.

“This witness is testifying to a science which directly concerns this case,” said the solicitor, “and I submit that it is absolutely relevant and admissible.

“There is no doubt that if Dr. Harris was the only man in the world who had made this experiment there would be an objection to his stating it by the defense.”

“You can give the results of your experiment or authority in the subject,” ruled Judge Roan.

Only One to Make Experiment.

“I know of none other who have made this experiment,” said the doctor, “and therefore I decided to make it myself. The stomach frees itself quickly of cabbage and bread. It frees itself as quickly of cabbage as it does of a mixture of the two.

“As soon as I saw the peculiar relation of cabbage to this case, I knew the girl had come to her death or to unconsciousness at the time digestion was stopped.”

At this juncture the witness was stopped by Mr. Rosser, who declared that the expert must give, or detail, the science of his statement.

“If that cabbage had been on my stomach,” said the attorney, “it would stay there until tomorrow.”

The solicitor protested to the objection, saying that Dr. Harris had already stated he was the only man who had ever made such an experiment.

It was following this assertion that the first injection of the Grace case was made into the Frank trial. Attorney Hooper brought comparison by reminding Judge Roan of a decision he had made in the famous case following an experiment by two marksmen with revolvers at police headquarters during course of the trial.

“Two men, who were not experts,” said Mr. Hooper, “went to police headquarters and, with pistols, determined the distance required to inflict powder marks upon a white cloth. There were no experts in the test, but there was an experiment, on which your honor ruled favorably.”

“You can give the science of your experiment, Dr. Harris,” ruled Judge Roan, “without disclosing the process by which your knowledge was gained.”

Girl’s Stomach Normal.

Following which came a declaration by Dr. Harris that the girl’s stomach was normal.

The defense frequently asked Judge Roan for rulings to objections which they made. In each instance it was specifically requested that particular note be made of it in the records. It was obvious that foundation was being laid for appeal for new trial.

During the course of an argument which followed an objection to certain parts of the expert’s testimony Attorney Rosser accused the witness of being intensely argumentative.

Dr. Harris continued:

“I recently experimented with four persons with cabbage cooked by Mrs. Coleman and in each case the effect upon them was the same, that is, pertaining to digestion. The results also were the same as found in Mary Phagan’s body.”

At this Dr. Harris attempted to display the vials of cabbage removed from the stomachs of the man on whom he had made the experiment. Attorney Rosser voiced objection.

“I want to show,” argued the solicitor, “that the stomach of Mary Phagan was normal, and that the cabbage discovered in her body was undigested. It is possible that this expert cannot explain his experiment and to show comparisons revealing that this cabbage was cooked alike, swallowed alike, and chewed alike by the men on whom Dr. Harris made the experiment.”

He was sustained.

Dr. Harris continued:

“Mary Phagan’s stomach was normal in size, development and position—in fact, it was normal in every particular.”

Believes Doctors Are Guessing.

At this, Mr. Rosser insisted that Dr. Harris tell his reasons for knowing these facts.

“I don’t know what the doctor means about this and about that,” he said, “for I think all these doctors are guessing most of the time.”

Judge Roan cautioned the witness to tell purely all he found in his explanation.

“I found in Mary Phagan’s case,” he said, “that even the particles finely chewed were not digested at all. Digestion had not gone on to any extent at the time of death or unconsciousness.”

It was while he was attempting to explain one of his own theories relating to this condition Dr. Harris was interrupted by Mr. Rosser, who said:

“You should not give your opinion, doctor, nor make any stump speeches.”

“It was clear that this cabbage had not entered the smaller intestines,” continued the witness, “which showed that the contents of the stomach had not been pressed into the intestines at the time of death.

“Also the amount of gastric juice in this case was less than would have occurred in an hour in an ordinary case. Hydrochloric acid forms at certain periods of digestion, and had not formed in this case of Mary Phagan. There was no free hydrochloric acid, but there were 32 degrees of combined hydrochloric acid.

Girl Dead in Forty Minutes.

“In this case, the combined hydrochloric was about the amount one would suppose to exist within thirty or forty minutes. I have assumed that the girl, after she ate, was dead within that length of time—thirty or forty minutes.

“Another question is the pancreatic juice would make its appearance in the stomach and intestines within that period. It was absent in this case.”

“Was failure to digest cabbage due to its condition?” asked the solicitor.

“No, the digestive fluid was there.”

“Was there any obstruction in the flow of the stomach’s contents?”

“None.”

“Would a blow or struggle check the process of digestion?”

“Yes.”

“Had digestion up the time of death progressed favorably?”

“Yes. Her digestion was normal.”

“Dr. Harris, will you please give the jury some idea of the power of magnification your microscope projected upon the stomach in your examination?”

“My microscope is the finest made. It could have enlarged objects thousands of times.”

“How did the state of bread correspond to the state of cabbage?”

“Just the same.”

“Suppose it had been chewed up entirely, would that have had any effect?”

“No; the effect would have been the same.”

At this point Attorney Arnold took up the cross-examination.

“Where did Mr. Dorsey first talk to you about this matter?” he asked.

“I don’t recall.”

Asked Him to Keep Silent.

“Did Mr. Dorsey request you not to make the result of this examination public?”

“Yes, sir. I told him I would take the case and go into it thoroughly. There were some suggestion of poison, and I made an examination for poison, but none was found.”

“Couldn’t a man be dying and all the appearance in this case be produced by putting a cord around his throat?”

“I think not.”

“A man might be dying from strangulation for an hour, mightn’t he?”

“Yes.”

“Having explained, doctor, that death by strangulation was more the result of the body retaining poisons than from the failure to get oxygen, you still state that his correct, eh?”

“Yes.”

“If breath was cut off completely, how long before a man would die?”

“No one has ever been able to ascertain definitely.”

“You say your first intention was to examine Mary Phagan’s body for poison?”

“Yes.”

“What kind of poison?”

“Alcolaid.”

“What else?”

“Strychnine or morphine.”

“Was there any arsenic in Gheesling’s embalming formula?”

“Yes.”

Made the Opium Test.

“What test did you make for poison?”

“The opium test.”

“Did you test for mercury?”

“Not directly.”

“For what mineral poisons did you test?”

“I did not test for mineral poisons.”

“Did you make the poison tests before you made the others?”

“I made them all at the same time.”

“In how many parts did you divide the contests [sic] of the stomach?”

“I divided them into all parts necessary; I do not recollect the exact number.”

“How many tests did you make?”

“Six or eight in all, all of which were necessary.”

“What was the first test?”

“To determine various quantities.”

“What was the second?”

“For hydrochloric acid.”

“How do you measure hydrochloric acid?”

“By degrees.”

“How many drops would 32 degrees form?”

Dr. Harris figured for several minutes on his notebook, multiplying, dividing, saying finally:

“About a drop and a half.”

Only Chemical Acids.

“What are the properties of free acid?”

“Chemical acid only.”

“Hydrochloric acid is a powerful property, isn’t it?”

“Very powerful.”

“The average man has how many degrees?”

“Fifty-five or sixty degrees—three or four drops.”

“What is the next juices of importance to the digestive organs?”

“Pepsin.”

“How much pepsin should there be to correspond with 32 degrees hydrochloric acid?”

“Unfortunately we have no accurate way of determining the measurements of pepsin.”

“Do different stomachs and glands produce various quantities of pepsin and hydrochloric acid?”

“Yes, there has been much argument on the subject.”

“Where does the pepsin come from that we get at soda founts?”

“From cows and animals.”

“it is purely an animal substance, then?”

“Yes.”

“What becomes of the juices in the body after death?”

“They evaporate gradually.”

“Embalming removes most of the fluids, doesn’t it?”

“Yes.”

Come From the Stomach.

“Gastric juices all come from the stomach, don’t they?”

“Yes.”

“How long, doctor, is the small intestine of which you speak?”

“About twenty-five feet.”

“Did you find any of the cabbage in Mary Phagan’s body to have been [e]mulsified?”

“Yes, I’ve already explained that.”

“What were the proportionate parts in her stomach?”

“Ninety per cent water, 10 per cent solid.”

“The important constituents, then, are in the solid, as the fluid amounts to but little?”

“Yes.”

“Is cabbage nourishing?”

“About as much as any other vegetable. No vegetable has any great amount of nourishment.”

“What gastric juice is created by the mouth?”

“Saliva.”

“Is that a digestive property?”

“Yes.”

“What chemical properties are in saliva?”

“It helps to digest the starch that goes into the stomach.”

Here Dr. Harris became slightly ill, and, at his request, was removed from the stand.

Had she been bitten on the breasts? X-rays of her body had apparently shown teeth indentations on her neck and shoulder. Where were the X-ray records? Were the marks made by Leo Frank's teeth? Did Solicitor Dorsey have Mary's body exhumed a second time to check the marks against X-rays of Leo Frank's teeth?

American *Jewish-Revisionists Scholars the Leo Frank Case (Oney,[ And the Dead Shall Rise, 2003, pages 617-618] *Dinnerstein,[ The Leo Frank Case, 1991 Special , page 158] *Golden, [ A Little Girl is Dead, 1965, pages 53-54; 256-257] *Alphin,[ An Unspeakable Crime, 2010; pages 11, 46, 132] *Melnick, [ Black-Jewish Relations on Trial; Leo Frank and Jim Conley in the New South, 2000; page 68], *Wilkes [Flagpole Magazine, May 5, 2004; page 7] and others) have cited that Mary Phagan had bitemarks on her neck and shoulder and state that this as factual evidence and indicates Leo Frank is innocent and should be exonerated.

In 1913, Kodak produced the first prepackaged dental x-ray film. The packet of waxed waterproof paper contained two pieces of single-coated film. This film basically was still photographic film. In 1919, Kodak produce the first true dental x-ray film, designed for direct exposure by x-rays.

First Court case in Georgia when dental x-rays were used:

1985: Henson

https://law.justia.com/cases/georgia/court-of-appeals/1985/69545.html

Atlanta Journal, August 3, 1913

"Both physicians [Dr. Harris, Dr. Hurt] and the undertaker agree that there were no beastly and unspeakable mutilations about the dead girl’s body, such as street rumor and gossip originally attributed to the perpetrator of the crime."

Mary Phagan was embalmed by William Gheesling at P.J. Bloomfield's Mortuary on late morning of April 27, 1913, and Dr. Hurt completed a post-mortem. Dr. Harris did an autopsy on May 5, 1913. None of these experts who examined the body of Mary Phagan ever reported bitemarks on her neck and shoulder, or anywhere on her body for that matter.

Mary Phagan was exhumed when a rumor that a girl that looked similar to her appeared to be on drugs, during the evening of the murder April 26, 1913. No bitemarks were ever reported anywhere on her embalmed body, during further examinations, or after exhumation on the morning of May 5, 1913.

During the trial of Leo Frank, numerous physicians' witnesses for both the State's prosecution and Defense team never mentioned bitemarks on Mary Phagan's neck and shoulder. Newspaper reports from the Atlanta Journal, Atlanta Constitution, and the Atlanta Georgian from 1913-1915 never mentioned bitemarks or photos of the teeth marks on her body did not correspond with Leo Frank's set of teeth of which several photos were taken. Governor John M. Slaton Commutation states does not mention evidence of bitemarks on Mary Phagan's shoulder, neck or anywhere else on her body [Chapter 7] and states "The body was not mutilated." Nowhere in the testimony can it be found that Mary Phagan was bitten on her breast.

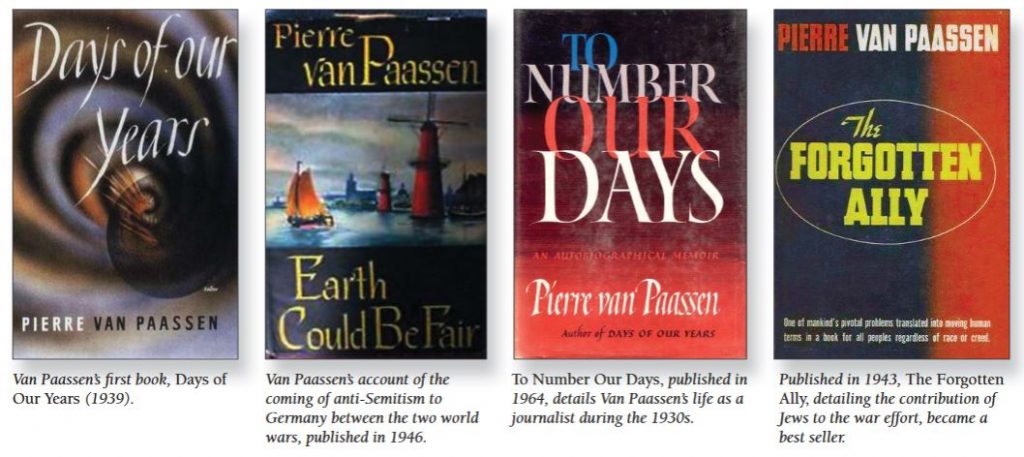

Where did these claims come from? The report of such a bite surfaced many years later when in 1964, Pierre Van Passen*, who had studied the evidence and X-rays of the Frank case in 1922, reported that he found X-ray pictures showing the girl had been bitten on the left shoulder and neck before strangulation, and that, moreover, those indentations did not correspond to the X-rays of Leo Frank's teeth.

*Pierre Van Passan published his book in 1964, To Number our Days. [Footnote 7] where he recollects memories back to 1922 when he was living and working at the capital in Georgia for the Atlanta Constitution. He claimed he found a file at the Fulton County Courthouse and found an envelope with a "sheaf of papers and number of x-ray photos showing teeth indentures."

To Number our Days

Pierre van Paassen, 1964; Pages 237-238

“The Jewish community of Atlanta at that time seemed to live under a cloud. Several years previously one of its members, Leo Frank, had been lynched as he was being transferred from the Fulton Tower Prison in Atlanta to Milledgeville for trial on a charge of having raped and murdered a little girl in his warehouse which stood right opposite the Constitution building. Many Jewish citizens who recalled the hanging were unanimous in assuring me that Frank was innocent of the crime.*Leo Frank was not hung as he was being transferred from the Fulton Tower Prison in Atlanta to Milledgeville. Slaton commutated his sentence on June 21, 1915 where he was moved to Milledgeville. Leo Frank was in Milledgeville until he was lynched on August 17, 1915.

“I took to reading all the evidence pro and con in the record department at the courthouse. Before long I came upon an envelope containing a sheaf of papers and a number of X-ray photographs showing teeth indentures. The murdered girl had been bitten on the left shoulder and neck before being strangled. But the X-ray photos of the teeth marks on her body did not correspond with Leo Frank’s set of teeth of which several photos were included. If those photos had been published at the time of the murder, as they should have been, the hanging would probably not have taken place.

“Though, as I said, the man died several years before, it was not too late, I thought, to rehabilitate his memory and perhaps restore the good name of his family. I showed Clark Howell the evidence establishing Frank’s innocence and asked permission to run a series of articles dealing with the case and especially with the evidence just uncovered. Mr. Howell immediately concurred,* but the most prominent Jewish lawyer in the city, Mr. Harry Alexander, whom I consulted with a view to have him present the evidence to the grand jury, demurred. He said Frank had not even been tried. Hence no new trial could be requested. *Frank was arrested, tried and convicted of Mary Phagan’s murder on August 25, 1913. Moreover, the Jewish community in its entirety still felt nervous about the incident. If I wrote the articles old resentments might be stirred up and, who knows, some of the unknown lynchers might recognize themselves as participants in my description of the hanging. It was better, Mr. Alexander thought, to leave sleeping lions alone. Some local rabbis were drawn into the discussion and they actually pleaded with Clark Howell to stop me from reviving interest in the Frank case as this was bound to have evil repercussions on the Jewish community.

“That someone had blabbed out of school became quite evident when I received a printed warning saying: ‘Lay off the Frank case if you want to keep healthy.’ The unsigned warning was reinforced one night or, rather, early one morning when I was driving home. A large automobile drove up alongside of me and forced me into the track of a fast-moving streetcar coming from the opposite direction. My car was demolished, but I escaped without a scratch….”

Did Pierre Van Paassen fabricate this claim as he did others including his personal life?

This post is a summary of a story in the print version of Origins, “Journalist, Author, and Zionist–Pierre Van Paassen,” by Gerlof D. Homan. Read the full story here: Issue 32:2 of Origins: Historical Magazine of the Archives (Fall 2014) or in the Appendix Section.

If you would like to read Van Paassen books, you can find them in the Hekman Library at Calvin University.

Pierre Van Paassen lived a life of contradictions. He was a pacifist who set aside his principles to serve in the Canadian military and later returned to pacifism of a sort. He was a journalist who made up stories and bounced around jobs from Canada to the United States, Europe, and Palestine. The longest continuity in Van Paassen’s work was his support for Zionism and the new state of Israel. What can we make of a life like his?

Life started for Van Paassen in a militant Calvinist household in Gorinchem, Netherlands. He wrote about his upbringing in numerous books, including one of his bestsellers, The Forgotten Ally. In 1911, Van Paassen immigrated to Toronto, Canada, where he left behind the Reformed Christianity of his parents to become a Methodist pastor. In 1914, he married Ethel Ann Russell, before separating from her and remarrying, this time a Gorinchem native named Cornelia Machelina Sizoo.

A writer more than anything else, Van Paassen spent much of his career in journalism. He worked for several newspapers, most notably as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star. Many of his stories were about war and racial violence. He penned articles about the dangers of National Socialism, comparisons between the Nazi party and KKK, and Nazi brutality towards Jews. Late in life, he wrote about the injustices faced by African Americans. Ironically, given his opposition to racial bigotry, the Toronto Star fired him in 1936 for his anti-Catholic, left-wing biases.

Van Paassen discovered his passion in the 1930s when he began to devote much of his time and energy to the Zionist cause. He found himself entranced by the trials and triumphs of the ancient Israelites. He became a Zionist activist, believing that Zionism was the “Social Gospel of Judaism” and that the Jewish people would create a model state.

To support the cause Van Paassen spoke to Christian and Jewish congregations. He joined the short-lived Pro-Palestinian Federation in the United States and served as chairman for the Committee for a Jewish Army for Stateless and Palestinian Jews. Van Paassen found himself writing letters and statements to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill on behalf of Zionist Committees. His sympathy for the persecuted Jewish population and the state of Israel never wavered throughout his life.

For all his activism, Van Paassen remained a writer at heart. He became an independent author after the Toronto Star let him go. His main interests were Zionism and his hometown of Gorinchem. His first book, the autobiographical Days of our Years (1939), was an instant bestseller. The Forgotten Ally (1943), about the contributions of Jews to the war effort, also reached bestseller status. His desire to tell vivid stories led him to make up material and commit factual errors, however. Earth Could be Fair (1946), ostensibly about Gorinchem during the war and based on family letters, was totally fabricated, for example.

Although Van Paassen’s writings were marred by errors and fabrications, readers loved them. “Van Paassen was a prolific writer who used his journalistic skills to warn against the dangers of National Socialism and to speak on behalf of the persecuted Jews,” Gerlof Homan concluded in his Origins article in 2014. “Unfortunately, much of his other writing has limited historical value as he tended to fictionalize events and individuals including aspects of his own life.” The flaws in Van Paassen’s books do not negate Van Paassen’s intuitive understanding of what interested readers or his impact as a supporter of Zionism.

After the war, Van Paassen returned to the church. In 1946 he became an ordained Unitarian minister. He criticized Christianity that looked to the afterlife for comfort and instead advocated a “militant Christianity” that promoted the Kingdom of God in the here and now. Perhaps Van Paassen’s life is best seen as that of a man in search of the right pulpit. He might have left behind his parents’ Calvinism, but not their inclination to support righteous causes.

Caleb Ackerman is a student at Calvin University.

************

Winter 2021, The Breman Museum Presents:

Atlanta Jewish History Talks THE TRAGIC CASE OF LEO FRANK THURSDAY JAN 28th | 10:30 AM - 11:30 AM

Join Steve Oney, the foremost historian on the Leo Frank case, as he discusses a devastatingly tragic case of Anti-Semitism in America and a pivotal moment in Atlanta’s Jewish history. The class will be moderated by founding archivist of The Breman, Sandra Berman, who devoted her career to collecting original historic items from the case and curated an in-depth exhibition that traveled around the country.

It was surprising that Steve Oney and Sandra Berman suggested the Autopsy Report did not exist and pushed the narrative of Pierre Van Passen that Mary Phagan was bitten on the neck and shoulder. Oney states in his book, And the Dead Shall Rise, The Murder of Mary Phagan and the hanging of Leo Frank, [pages 91-93; 233-234; 257-258] the "autopsy report" which never mentions the bitemarks. To still use this reference today as proof of Leo Frank's innocence is a deliberate effort of misrepresenting historical sources.

Was Leo Frank a "pervert," as the state attempted to establish? The state had certainly enough people to state on the witness stand that he'd made sexual overtures to the female employees at the factory. But does that mean—did the answers to any of my questions mean—that Leo Frank killed Mary Phagan?

On the Saturday following the murder, Monteen Stover, a fellow worker at the factory with Mary Phagan, came forward to tell the police that she had come for her pay on April 26 but was unable to collect it because Frank was absent from his office.

Monteen informed the police that "it was five minutes after twelve. I was sure that Mr. Frank would be in his office, so I stepped in. He wasn't in the outer office, so I stepped into the inner one. He wasn't there either. I thought he might have been somewhere around the building so I waited. I went to the door and peered further down the floor among the machinery. I couldn't see him there. I stayed until the clock hand was pointing to ten minutes after twelve. Then I went downstairs. The building was quiet, and I couldn't hear a sound. I didn't see anybody."

On April 30, 1913 coroner's inquest began.

*Note: In 2013 on the 100th anniversary of Mary Phagan’s sexual assault and murder, a full unexpurgated digital record of all the contemporary reports about the Coroner’s Inquest which took place in the wake of the murder of Mary Phagan became available.

The full text of every single article from the Atlanta Georgian, the Atlanta Constitution, and the Atlanta Journal that dealt with the 1913 Coroner’s Inquest is reproduced in Part 2. It was at the Coroner’s Inquest that Mary Phagan’s death was legally declared to be a result of willful murder and that official suspicion was first leveled at the last person to see her alive: Leo Frank, factory superintendent.

When a person is killed under unusual or suspicious circumstances in the United States, the first investigation into what may well be a crime is conducted by the coroner of the county where the death took place and is called an inquest. Presiding over the inquest and its investigations is the coroner, who is assisted in reaching a decision by a coroner’s jury. At an inquest, witnesses may be called and examined, documents may be offered into evidence, expert medical and other opinion may be taken, and suspects may be questioned. Such was the case in Fulton County, Georgia, when Mary Phagan’s tragic death occurred on April 26, 1913. A coroner’s inquest can render verdicts of, for example, natural death, accidental death, misadventure, suicide, or murder. If the verdict is murder, the jurors will often recommend that a certain person or persons be held on suspicion of committing the crime. The responsibility for continuing the case then falls to the criminal justice system.

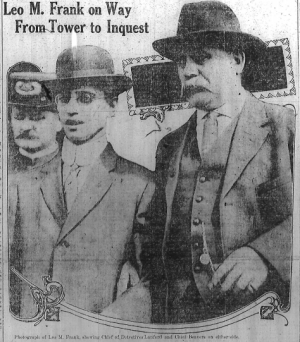

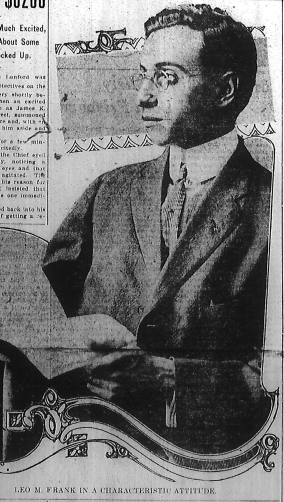

Leo Frank being taken from the Tower to the Coroner’s Inquest (from the Atlanta Georgian, Monday, May 5, 1913). He was accompanied by Chief of Detectives Lanford (left) and Police Chief Beavers (cut off on the right in this photograph)

.

Presided over by the Fulton County Coroner Paul V. Donehoo were a half-petit jury of prominent White men from the community, who opened the Coroner’s Inquest on Wednesday morning, April 30, 1913.

The inquest began shortly after nine o’clock after the jury members were sworn. The empaneled tribunal in total consisted of seven men — Coroner Donehoo and the six jurymen: 1. H. Ashford, foreman; 2. Glenn Dewberry; 3. J. Hood; 4. C. Langford; 5. John Miller; 6. C. Sheats; and 7. Judge of the Inquest Jury, The Fulton County Coroner, Paul Donehoo.

Paul Donehoo — who made up for the fact that he was legally blind with his brilliant logical mind and quick insight into human character and motivations — quickly began to focus on certain contradictions and oddities in the testimony he’d heard.

Never used the bathroom?

- In Donehoo’s two examinations of Leo Frank, Frank repeatedly and unequivocally stated under oath that he did not use the second floor bathroom in his factory at all on the day of the murder, even though he spent almost all of that day in his office on the same floor. Frank did not state that he didn’t remember — but rather that he did not use that bathroom (the one he customarily would use) on April 26, 1913. There were no other bathrooms on the second floor of the National Pencil Company, except in the metal room (see Brief of Evidence, 1913 Defendant’s Exhibit 61). This was originally thought by many to be a “throw away” detail, but later it became one of the most profound links in the case.

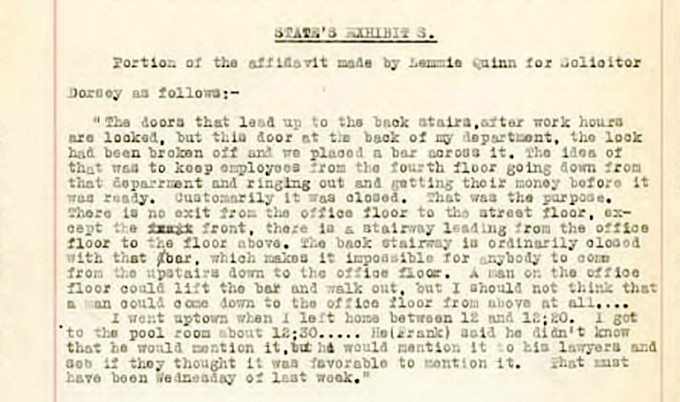

The visit that wasn’t — and then was

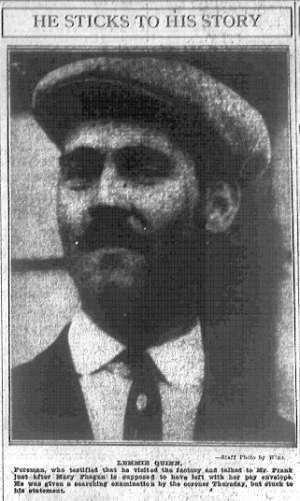

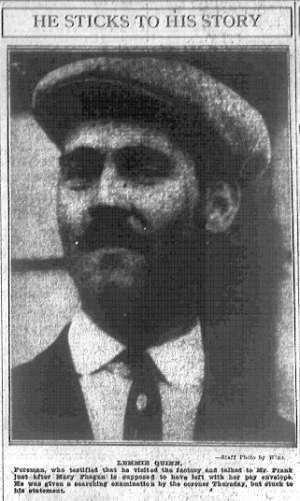

- A controversial new development occurred during the inquest concerning Leo M. Frank’s alibi for the 45 minutes after Mary Phagan visited him in his office at noon. Frank said he never left his office on the day of the murder between noon and 12:45 PM, but there was no way to even remotely corroborate this. But then Leo Frank said he had forgotten for the entire first week of the murder investigation to bring forward his employee Lemmie A. Quinn, the foreman of the metal room, who then testified at the Coroner’s Inquest that he had returned to the factory and seen Frank in his office around 12:20. Quinn also testified that he had not mentioned this before because he had wanted to give Frank a chance to ask his attorneys if such testimony would be “helpful.” (Much later, after Frank’s conviction and during the appeals process, Quinn was criminally impeached when it was discovered he was offering bribes to witnesses to change their stories.)

Lemmie Quinn signed an affidavit for Solicitor Dorsey one week before the Coroner’s Inquest, stating he had gone to play billiards after he left the National Pencil Company factory at a quarter to noon (11:45am), and he does not ever mention coming back to the factory. He changed his story at the inquest, stating he had come back to the factory at 12:20pm to speak with Leo Frank. When Coroner Donehoo asked Leo Frank why he waited a week to bring forward this critical alibi witness to the police, Leo Frank said he wanted to wait for his lawyers’ “permission” first.

Quinn told the Coroner’s Inquest jury that he went back to the pencil factory and specifically into Leo M. Frank’s office at 12:20 to 12:25 PM for the purpose of talking about a baseball bet with the factory’s head clerk, Mr. Herbert George Schiff. But Schiff was not at the factory, and was not even supposed to be at the factory at all that day, because it was a State holiday and everyone was given the day off.

Herbert G. Schiff stated at the later Leo Frank trial that he took pride in the fact that he had never missed a day of work in five years (Brief of Evidence, Herbert Schiff, 1913) — except once, unintentionally, during a disastrous flood. Leo Frank, however, gave the false impression that Schiff unexpectedly missed work that day — in order to make Quinn’s suddenly-remembered appearance seem less improbable.

Some of the questions to and about Quinn and his visit were quite pointed:

- Did you tell any of the officers that you had not been at the factory since Friday?—A [Quinn]. No.

- You didn’t tell Officer Payne?—A. No.

- You didn’t tell Detective Starnes?—A. No.

. . .

- Did you talk to Frank about your being in the office on Saturday?—A [Quinn]. I refreshed his memory of my being there.

- When?—A. I don’t remember the exact date. It was after he had been locked up.

- How did you refresh his memory?—A. We were discussing the supposition of the girl having never left the factory. I told him: “Why I was there Saturday after the time you say Mary Phagan was.” He said he remembered me being there, but wasn’t sure of the time. I told him what time it was and he said he would tell his lawyers. I told him I did not want to be drawn into the case, but if it would help him I would do so.

- Were you alone with Frank when you talked of this?—A. Yes.

. . .

Coroner Donehoo tried to get Quinn to admit that he previously had told officers who interviewed him that he was not at the factory between Friday and the following Sunday.

. . .

An effort was made without avail to break down the story of Lemmie Quinn that he was at the factory and talked to Frank between 12:10 and 12:20 the Saturday afternoon of the tragedy. Coroner Donehoo tried to get Quinn to admit that he previously had told officers who interviewed him that he was not at the factory between Friday and the following Sunday.

. . .

Detectives declared that Quinn had told them and other persons that he did not visit the factory at all Saturday and that he was not there from the time he left Friday until the following Monday.

. . .

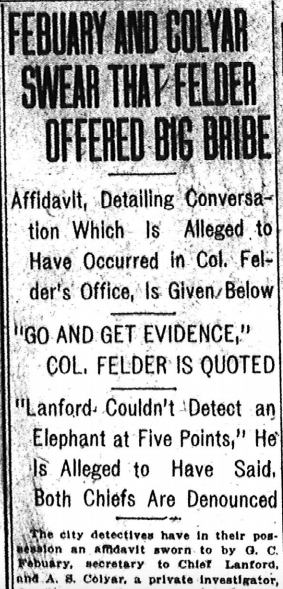

A stormy scene is said to have ensued during the interrogation to which he [Quinn] was subjected at headquarters. To a reporter for The Constitution, he last night declared that Scott and Solicitor Dorsey charged him with having accepted a bribe from Frank’s counsel for the story he was telling of the visit to the factory.

. . .

Detective Black contradicted the testimony given at the morning session by Lemmie Quinn by saying that Quinn had told him the Monday after the tragedy that he had not been to the pencil factory the Saturday before.

“Quinn made the statement in my presence two or three times,” said the witness. “On one occasion Detectives Starnes and Campbell questioned him in the basement of the pencil factory and he said he had not been there.”

Herbert Schiff: In an effort to help Frank, Lemmie Quinn claimed he returned to the factory to talk to Schiff. But why would he do that on a day when Schiff was expected to be absent?

Lemmie Quinn signed an affidavit for Solicitor Dorsey one week before the Coroner’s Inquest, stating he had gone to play billiards after he left the National Pencil Company factory at a quarter to noon (11:45am), and he does not ever mention coming back to the factory. He changed his story at the inquest, stating he had come back to the factory at 12:20pm to speak with Leo Frank. When Coroner Donehoo asked Leo Frank why he waited a week to bring forward this critical alibi witness to the police, Leo Frank said he wanted to wait for his lawyers’ “permission” first. (Excerpt from State’s Exhibit S shown)

It was, doubtless, obvious to Donehoo and the Coroner’s Inquest jury that the testimony of Quinn was meant to shrink the plausible time Leo M. Frank would have to bludgeon, rape, and strangle Mary Phagan by 15 minutes — from, formerly, 12:02 PM to 12:35 PM to, if Quinn was to be believed, 12:02 PM to 12:19 PM. Ultimately, Quinn’s testimony as regards his alleged visit had little if any helpful effect for Leo Frank. If anything, it called into question the veracity of Frank and his defenders and ultimately the innocence of Frank himself:

Would an innocent man resort to such devices?

Improper behavior toward teenage girl employees

- Also significant in Donehoo’s view was Frank’s efforts at promiscuous sexual advances toward some of the girls he employed, as evidenced by this reported testimony:

Girls Testify Against Frank.

The most damaging testimony against Frank in regard to his treatment of employees at his factory was saved until the last hours of the hearing. Girls and women were called to the stand to testify that they had been employed at the factory or had had occasion to go there, and that Frank had attempted familiarities with them.

Nellie Pettis

Nellie Pettis, of 9 Oliver Street, declared that Frank had made improper advances on her. She was asked if she ever had been employed at the pencil factory.

“No,” she answered.

- Do you know Leo Frank?—A. I have seen him once or twice.

- When and where did you see him?—A. In his office at the factory whenever I went to draw my sister-in-law’s pay.

- What did he say to you that might have been improper on any of these visits?—A. He didn’t exactly say—he made gestures. I went to get sister’s pay about four weeks ago and when I went into the office of Mr. Frank I asked for her. He told me I couldn’t see her unless “I saw him first.”

Says He Winked at Her.