Last Updated on July 26, 2024 by Mary Phagan

At the end of February 1978, my coworkers at Griffin CESA jokingly told me I was on the front page! Silence fell over the room. The look in my face must have told them something: it couldn't be. Why was it on the front page now? It seemed I could never escape.

I picked up the newspaper. It was the Atlanta Constitution. The banner headline read: "THE MURDER OF MARY PHAGAN" by Celestine Sibley. A preface before the story indicated that they were doing a series on famous murders in Georgia. My father and I found several inaccuracies in the articles on Mary Phagan and felt we had to voice our opinion to the author.

My father called Celestine Sibley, but the call was never returned. He was surprised.

Several other Phagans were quite upset by the articles. John Phagan Durham, son of Lizzie Mary Etta Phagan, who made little Mary's dress, and first cousin of little Mary Phagan, went to Mr. Sears, the Managing Editor of the Atlanta Constitution and asked that the articles be stopped. He said that Mr. Sears replied: "We cannot stop the articles, and if we have caused hard feelings with the Phagan family we apologize. And if you would correct the factual inaccuracies, we would correct them." Phagan Durham informed Mr. Sears that he, Phagan Durham, would not make the corrections because the series appeared on the front page, and he was certain the corrections would not appear on the front page. People would not see them. He left, frustrated.

The series rekindled interest concerning the murder of little Mary Phagan and its aftermath. Principals, teachers, students, optometrists, and ophthamologists in the eight counties my work covered asked me that question: "Are you, by any chance, related to little Mary Phagan?"

The questions became more intense: people wanted details on the trial and the lynching and wanted to know if any of the Phagans were involved with the lynching. I wanted the truth to be known.

I wanted the inaccuracies corrected. I became more articulate in discussing the case, and I felt a sense of confidence since I knew the story well and could answer most of the questions.

I had plans to marry in June of that year. Bernard knew nothing of the story of little Mary Phagan. I had never told him. He, like most, had read the series in the newspapers, and one night he mentioned that a girl was murdered who had my name; then he, too, wanted to know: "Are you, by any chance, related to her?"

"Yes," I said, "I am."

Why, he wanted to know, had I never told him?

"You never asked," I said.

Then I told him: I told him the story and why the Phagan family had remained silent. But, I told him, we had something to say now, and my father agreed and was beginning to let it be known that there were close relatives of little Mary Phagan who were still living.

Daddy hadn't gone so far as to publicly acknowledge our existence but had let certain individuals know in nonchalant ways.

Bernard asked if I had ever been to the grave. I hadn't.

I was bothered that my name was on a tombstone. Right then we determined to go.

We drove to Marietta. I was extremely quiet, and Bernard responded with silence. It was time: I felt the desire to go to the grave.

It was a beautiful day—sunny, with a light breeze. As we neared the cemetery, I began to feel sick to my stomach. Now I wasn't quite sure if I wanted to see the grave.

"We're here," Bernard said suddenly.

I hesitated. "Are you all right?" he asked. Somehow, I felt inner strength. "I'm ready,"

I told him softly.

The plot was located in the wealthy section of the cemetery. There, beside little Mary, were other Phagan family members, including William Jackson Phagan and Angelina O'Shields Phagan.

Little Mary Phagan's grave was like none other that I had seen before. It had a marble tombstone which bore her name and an inscription the length of the burial place in marble. It was a beautiful inscription and was written by Tom Watson. I immediately memorized it.

Bernard and I took photos for the scrapbook about Mary I had begun assembling. A middle-aged couple approached us and asked if we knew where the grave of little Mary Phagan was. The articles in the newspaper had once again revived interest in her.

A sense of sadness for my relatives, especially those who had lived through the horrible ordeal, came over me. And I admired them for not seeking publicity and wishing to remain anonymous.

That year, 1978, proved to be full of beginnings and firsts for me. It was the first time my father had acknowledged our relationship to Mary by contacting a reporter; the beginning of a scrapbook of little Mary Phagan; my first visit to the grave of little Mary Phagan; and my first car accident—which turned out to have a connection to Mary Phagan.

A few days after the accident I decided to check on the elderly lady who had struck my car and to find out if she had turned in the insurance papers. She was a wealthy, prominent member of the community in which she lived. Her house was extraordinarily beautiful. When she answered the door, I explained that I was the individual involved with her in the accident, and I was checking to see if she had turned in the insurance papers. She welcomed me inside her home and told me that she was becoming blind and deaf and did not have anyone to help her fill out the forms. She asked me if I would help. I filled out the paperwork, and, with a magnifying glass, she read it to correct the errors. When she came to my name, she abruptly turned to me and asked me that question: "Are you, by any chance, related to little Mary Phagan?"

When I said "Yes," she hugged and kissed me. Then she related her memories of it.

She and her husband drove their horse and buggy to Atlanta and saw the crowd of people waiting to hear the trial. Apparently it had been an overwhelming sight. The majority of the people at that time felt that Leo Frank was guilty, she said, and she believed it too. She still believed it. She excitedly told me about life in that era and how many changes she had seen in her ninety-two years. She liked some of the changes, but others she disliked. I had a wonderful time, and she invited me to have lunch with her. She had found that I listened to her attentively, and nowadays it seemed that no one really listened anymore.

The next day, I received another invitation for lunch. For the rest of the school year, I would lunch with her on Mondays. We became very close.

In 1980, Bernard and I moved to Cobb County, where my family had begun. Since the travel was too far and too much for me, I resigned my position at Griffin CESA and began employment for the Cherokee County Board of Education in Canton, Georgia as the itinerant teacher for the blind and visually impaired.

When school began in August, my supervisor introduced me to the principals for whom I would be working. Several of them asked me that recurrent question: "Are you, by any chance, related to little Mary Phagan?"

At one of the schools the principal was not available to meet me, but as we were leaving, he ran out after us and asked me my name and what position I held for the county. He took out his pen from his shirt pocket, and as I told him my name, he wrote it on the palm of his hand. He stared at it and asked me that question.

I told him "yes."

He erased my name from his hand and told me he would never forget my name. From that moment on, Mr. Tippens called me "little Mary Phagan," and introduced me as such. I didn't mind.

ALONZO MANN

On Saturday, March 6, 1982, Sue Youngblood, one of the secretaries where I worked, called. She was very upset. She had been watching television and heard a promotional late news headline, something to the effect of: "An eyewitness says Leo Frank was not guilty of the murder of little Mary Phagan. More details on the eleven o'clock news.

Stunned and bewildered, I waited for the hours to pass. How could there be a witness alive?

The local news provided a report from two reporters, Colin Sedor from Georgia, and Jerry Thompson from Tennessee. They discussed the era of the crime and the basic facts of the case. Then they showed an interview with Alonzo Mann, a man who said he had seen Jim Conley with the body of Mary Phagan. Mann, now eighty-three years of age and living in Virginia, appeared calm and competent as he spoke of these events.

Alonzo Mann claimed that he had attempted to relate what he had seen for years—and that no one seemed interested. After a while, he told reporters, he had given up.

He told reporters of the Tennessean that as a soldier during World War I he'd engendered a heated argument with another soldier—who happened to be from Georgia—when he said that he knew that Leo Frank did not kill Mary Phagan.

Over the years he told his wife, his relatives, and his closest friends his story. During the 1950s, he told it to a reporter of an Atlanta newspaper. But, Mann stated, the reporter said he didn't want to stir up the anti-Semitism that had engulfed Atlanta during the trial and at the time of the commutation. "Mrs. Frank is still alive," the reporter had also said, "and we wouldn't want to do anything to cause her any more grief."

At about the time he gave his testimony to the media, Mann agreed to a polygraph test and a psychological stress analysis.

The psychological stress analysis electronically measures and charts, with a needle and graph, the stress in the voice in response to questions: the greater stress there seems to be, the greater the probability that the subject is not telling the truth.

The polygraph, broadly used by law enforcement personnel across the United States, tests whether the subject is telling the truth by measuring the respiratory rate, blood pressure, skin reaction, and pulse rate.

In both procedures, the subject responds to questions and a pattern is printed out on graph paper connected to the machines which are connected to the subject's body.

Alonzo Mann, according to both tests, told the truth consistently.

Alonzo Mann's story was a new twist on the facts presented since 1913. He said that Jim Conley had said to him, "If you ever tell anyone, I'll kill you." He had gone home and repeated what he had seen and what he'd been told by Conley to his mother. She told him to be quiet, and he had been.

Now, after almost seventy years of silence, he decided to come forward to be at peace in his heart.

I wasn't the only one who was stunned. And I could not believe that Alonzo Mann would wait seventy years to reveal his eyewitness testimony. My father and I discussed at length the plausibility of Alonzo Mann's statements. We decided to remain silent until the sensationalism of the story quieted down.

It didn't.

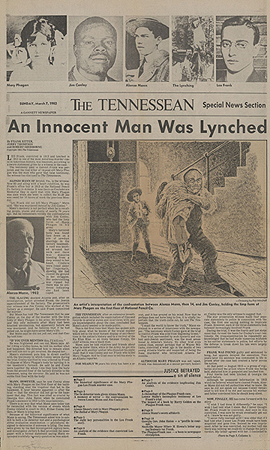

On March 7, 1982 the Nashville Tennessean ran a special supplement which bore the headline, "AN INNOCENT MAN WAS LYNCHED." The copy began, "Leo Frank, convicted in 1913 and lynched in 1915, in one of the most notorious cases in American history, was innocent, according to sworn testimony by a witness in the case."

The section contained quotations of the letters Leo Frank wrote his family from prison, Alonzo Mann's statement—and the print-out of the polygraph test he had taken. It contained photos of him at Mary Phagan's grave. The supplement was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

Between the publication of that special supplement and Alonzo Mann's appearance before the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles, reporters on the staff of the Tennessean initiated plans for a book, and had even spoken to the producer of the television miniseries, "Winds of War." Pardon Board Chairman Mobley Howell was quoted as saying that the entire affair had taken on a "showman quality."

Also, on March 7, 1982 Cassandra Clayton, another local reporter, reported an interview with Bernie Dukehart, brother of one of the members of the lynching mob, in which Dukehart said that Alonzo Mann's statements changed nothing and that his brother always felt that Leo Frank was guilty. On the same newscast there was an interview with Jasper Yeomans, the son of Leo Frank's defense attorney. The reporter also spoke briefly with Stuart Lewengrub of the Anti-Defamation League, who expressed the desire that a posthumous pardon be granted. It was also reported that the Phagan family members denied the station's request for an interview and were tired of their name being dragged through the mud. The Phagan family member who denied the interview was John Phagan Durham.

Ironically, at this point no one in the media knew that either my father or I existed. And several older Phagan's who had lived through the murder and its aftermath had also kept silent, even though the media contacted them. They did not discuss the case with even their closest friends.

On March 8, 1982 a review of the story appeared, with the conclusion that a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank was unlikely.

Alonzo's testimony read:

IN THE STATE OF TENNESSEE, COUNTY OF SULLIVAN

The undersigned, being duly sworn, deposes as follows:

My name is Alonzo McClendon Mann. I am eighty-three years old. My father was Alonzo Mann, who was born in Germany. My mother was Hattie McClendon Mann. When I was a small boy my family moved to Atlanta where I spent most of my life.

In 1913 I was the office boy for Leo M. Frank, who ran the National Pencil Company. That was the year Leo Frank was convicted of the murder of Mary Phagan. I was fourteen years old at the time. I was called as a witness in the murder trial. At that time I was put on the witness stand, but I did not tell all that I knew. I was not asked questions about what I knew. I did not volunteer. If I had revealed all I knew it would have cleared Leo Frank and would have saved his life.

I now suffer from a heart condition. I have undergone surgery to implant a pacemaker in my heart. I am making this statement because, finally, I want to have the record clear. I want the public to understand that Leo Frank did not kill Mary Phagan.

Jim Conley, the chief witness against Leo Frank, lied under oath. I know that. I am certain that he lied. I am convinced that he, not Leo Frank, killed Mary Phagan. I know as a matter of certainty that Jim Conley—and he alone—disposed of her body.

Jim Conley threatened to kill me if I told what I knew. I was young and I was frightened. I had no doubt Conley would have tried to kill me if I had told that I had seen him with Mary Phagan that day.

I related to my mother what I had seen there at the pencil factory. She insisted that I not get involved. She told me to remain silent. My mother loved me. She knew Conley had threatened to kill me. She didn't want our family's name to be involved in controversy or for me to have to be subjected to any publicity. My father supported her in telling me to remain silent. My mother repeated to me over and over not to tell. She never thought Leo Frank would be convicted. Of course, she was wrong. Even after he was convicted my mother told me to keep secret what I had seen.

I am sure in my own mind that if the lawyers had asked me specific questions about what I had seen the day of Mary Phagan's death I would have told the whole truth when I testified at Frank's trial.

Of course they didn't suspect what I knew. They asked me practically nothing. I was nervous and afraid that day. There were crowds in the street who were angry and who were saying that Leo Frank should die. Some were yelling things like "Kill the Jew!"

I was very nervous. The courtroom was filled with people. Every seat was taken. I was interested mostly in getting out of there.

I spoke with a speech impediment and had trouble pronouncing the "r" in Frank's name in those days. The lawyers put their heads together and said that it was obvious I knew nothing and since I was so young they would let me off the stand. It was not an easy place for a young boy to be, there in court like that.

I never fully realized until I was older that if I had told what I knew Leo Frank would have been acquitted and gone free. Instead he was imprisoned.

After he was convicted my mother told me there was nothing we could do to change the jury's verdict. My father agreed with her. I continued to remain silent. Later, Frank was lynched by a mob from Marietta, Georgia. I know, of course, that because I kept silent Leo Frank lost his life.

I have spent many nights thinking about that. I have learned to live with it.

I now swear to the events I witnessed that fatal day, Confederate Memorial Day, 1913, when Mary Phagan, who was just about my age, fourteen, was killed.

I came to work on time that morning, at about eight o'clock. I rode the streetcar from my home, on South Gordon Street, and when I walked into the building Jim Conley, the janitor, who also was called a "sweeper," was sitting under the stairwell on the first floor of the building. Although it was early in the morning, Conley had obviously already consumed considerable beer. He drank a lot, even in the mornings.

He spoke to me. He asked me for a dime to buy a beer. A dime could buy a good-sized beer in those days.

I told Jim Conley I didn't have a dime. That was not the truth. I had some money in my pocket, but I had let Conley have a nickel or a dime for beer before. He never paid me back.

I didn't like to be around Jim Conley.

After I told Conley I didn't have any money I went up the stairs to the second floor where my desk was located in the office of Leo Frank.

My job required that I open the mail, file papers, keep the office orderly, run errands, and the like. Leo Frank arrived in the building that morning shortly after I did. He came into the office and spoke to me. I always called him "Mister Frank" and he referred to me by my given name, "Alonzo." I do not know whether Leo Frank had seen Jim Conley on the first floor when he came into the building that morning.

A substitute secretary worked for Leo Frank that morning. As I remember, it was a routine Saturday morning for me at the office. Because of Memorial Day the factory part of the company was closed. But sometimes on Saturday mornings people who had worked at the factory during the week would come to the pay window in the office and collect their salaries. Girls who worked in the factory made about twelve cents an hour.

I did not know Mary Phagan by name, but I had seen her at the factory and knew her face. We were just about the same age.

I was supposed to meet my mother that day about noon and go to the Confederate Memorial Day parade. When I left the premises, just before noon, Mary Phagan had not come to the pencil factory. She apparently came to pick up her pay shortly after I left to go meet my mother.

Sometime after 11:30, and perhaps as late as quarter to twelve, I told Mr. Frank that my mother wanted me to meet her so that I could go to the parade with her. I didn't care all that much about seeing the parade, but my mother wanted me to go.

Mr. Frank agreed for me to leave at that time. I told him I would return to the office and complete my filing work later in the afternoon. He said he expected he would still be there.

When I left the company premises, just before noon, Mary Phagan had not come to collect her pay. When I left the building, down the stairs and out the first floor front door, Jim Conley, the janitor, was sitting where I had seen him when I came to work: in the darkened area of the stairwell.

I walked to the point where I was supposed to meet my mother. It was a short distance—perhaps a block and a half. We had agreed to meet in front of a store on Whitehall Street. My memory is that my mother had planned to buy a hat that day. I stopped and bought a hotdog on the way to meet her. However, when I arrived, she was not there. She had told me that if she was unable to come, for me not to worry. I waited for her for a few minutes. Since I didn't care that much about seeing the parade, I went back to work.

I can't be sure as to exactly how long I was gone, but it could not have been more than a half hour before I got back to the pencil factory.

I had no idea that I was about to witness an important moment in a famous murder case—a moment that has not been made public until now; that I was about to become a witness to tragic history.

I walked into the building by the front door.

Inside the door, I walked toward the stairwell. I looked to my right and I was confronted by a scene I will remember vividly until the day I die.

Jim Conley was standing between the trapdoor that led to the basement and the elevator shaft. I have an impression that the trapdoor was partially open, but my eyes were fixed on Jim Conley.

He had the body of Mary Phagan in his arms. I didn't know it was Mary Phagan. I only knew it was a girl.

At that moment I couldn't tell if she was alive. She appeared to be unconscious, or perhaps dead. I saw no blood.

He was holding her with both arms gripping her around the waist. I can't remember the color of her clothes but I have an impression that she had on pretty, clean clothes. She was extremely short and her head was sort of on his shoulder, or over it. Her hair was streaming down his back. Her hair was not in braids when I saw her. It was hanging loose. I saw no blood on the part of her neck that was exposed. I do not know if she was dead, but she was at least unconscious. She was limp and did not move. Her skirt had come up to about her knees.

It was as I suddenly barged into the first floor, prepared to go up the stairs to the office that I en-countered Conley with the body of Mary Phagan.

Conley was close to the trapdoor that led down into the basement by way of a ladder. I believe that from the direction he was headed and the attitude of the body that he was preparing to dump Mary Phagan down the trapdoor. I have no clear memory of whether the elevator had stopped on the first floor, but if it was not on that floor, the shaft would have been open. Conley could have dumped her down the empty elevator shaft. I believe for some reason Jim Conley turned around toward me. He either heard my footsteps coming or he sensed I was behind him. He wheeled on me and in a voice that was low but threatening and frightening to me, he said:

"If you ever mention this I'll kill you."

I turned and took a step or two—possibly three or four steps—up toward the second floor, but I must have worried about whether the office upstairs was closed. I did hear some movement upstairs, but I can't be sure who was on the floors above. I was fearful that the office might be closed, and so I turned back toward Conley. I wanted to get out of there quick. He got to within eight feet of me. He reached out as if to put one arm or hand on me. I ran out of the front door and raced away from that building.

I went straight home. I rode the streetcar.

Once at home I told my mother what I had just seen. I told her what Jim Conley had said to me about killing me. I didn't know for sure that the girl in his arms was dead.

My mother was very disturbed by what I told her. She told me that I was never, never to tell any-body else what I had seen that day at the factory. She said she didn't want me involved, or the family involved, in any way.

She told me to go on about my business as if nothing had happened and that sometime soon I would have to quit working there. From then on, whenever I was at work I steered clear of Jim Conley. I kept away from him and he did the same.

When my father came home my mother explained to him what I had seen and what Conley had said to me. My father told me to forget it and never mention it.

My mother was a very strong-willed woman who was thirty years younger than my father and he said to me what she wanted him to say.

Later on he told me that Frank would never be convicted.

I have wished many times that my mother hadn't taken that attitude and that either she had told the authorities or that she had encouraged me to tell somebody—perhaps Leo Frank—what I had seen.

When the detectives later questioned me I told only the part of the story up to the time I left that day to go meet my mother. I did not tell that I had come back into the building and saw Conley with the body.

When Frank went on trial and I was called as a witness, my mother told me I would have to go and testify. She told me to keep to myself what I had seen. She said if I were not asked a specific question I did not have to give a specific answer.

Jim Conley was the chief witness against Leo Frank. He testified that Frank had called him to his office a little after noon that day and told him that Mary Phagan's body was in the Metal Room on the second floor.

He testified that Frank told him to get the body and take it on the elevator down to the basement. He swore that he tried to carry the body to the elevator but dropped Mary Phagan because she was too heavy for him to carry. According to Conley's testimony, Frank picked up her legs, while Conley lifted the upper part of her body. Conley said that Frank had pulled the rope to start the elevator down and that they went with the body directly to the basement, past the first floor without stopping there.

Conley claimed that Frank dragged the body from the elevator to a point in the rear of the building. Conley contended during the trial that after Frank dragged the body away from the elevator, Conley ascended in the elevator and Frank came back up-stairs by way of the trapdoor to the first floor, and then came on up the stairway from the first to the second floor.

I know that all of that testimony was false. It was Conley who had the body on the first floor. He was alone with the body. Frank was not there on the first floor. Conley did not tell the truth when he said the body was taken from the second floor to the basement. He had the body on the first floor.

I know from what I read of the case that Mary Phagan had come into the building shortly after I went out to meet my mother. She went upstairs to the second floor. Leo Frank had given her her pay envelope. I understand that she had worked one day that week and she was entitled to about $1.20.

I am convinced that she had left the pay window and was coming down the stairs or had reached the first floor when she met Conley, who had been looking for money when I came in that morning. I am confident that I came in just seconds after Conley had taken the girl's money and grabbed her. I do not think sex was his motive. I believe it was money. Her pay was never found in the building after she died.

Many times I have thought since all of this occurred almost seventy years ago that if I had hollered or yelled for help when I ran into Conley with the girl in his arms that day that I might have saved her life. I might have. On the other hand, I might have lost my own life. If I had told what I saw that day I might have saved Leo Frank's life. I didn't realize it at the time. I was too young to understand.

As the years have gone by I have told this "secret" to a number of other people. I told it when I was in the Army in World War I. In fact, I had a fight with another soldier who became angry when I said Leo Frank did not kill the girl, but that Conley did. I have told other people. I told my late wife. She urged me not to make it public because she felt it wouldn't do any good. She said it would not bring back Leo Frank and it would not bring back Mary Phagan. And I told other relatives and friends. On one occasion, I believe in the 1950s, when I was operating a restaurant, I discussed this with a reporter in Atlanta. But the reporter said that since Leo Frank's wife was still alive it was not a matter the newspaper wanted to open up.

Leo Frank was convicted by lies heaped on lies. It wasn't just Conley who lied. Others said that Leo Frank had women in the office for immoral purposes and that he had liquor there. There was a story that he took women down in the basement. That cellar was filthy. It was filled with coal dust. I was in the basement twice and remember the dirt and filth there. That was all false.

Leo Frank was a good office manager. He was always proper with people who worked for him. There were witnesses who told lies and I remained silent.

Now I am finally making all this public. I have found reporters, Jerry Thompson and Bob Sherborne, who have heard my story and who understand that it is a case that is important to history. I am glad to have it all come out.

At last I am able to get this off my heart.

I believe it will help people to understand that courts and juries make mistakes. They made a mistake in the Leo Frank case. I think it is good for it all to come out, even at this late date.

Alonzo McClendon Mann

Sworn to and subscribed before me this 4th day of March, 1982.

Charles M. Gore - Notary Public

My Commission expires:

May 18, 1985

There will be some people who will be angry at me because I kept all this silent until it was too late to save Leo Frank's life. They will say that being young is no excuse. They will blame my mother. The only thing I can say is that she did what she thought was best for me and the family. Other people may hate me for telling it. I hope not, but I am prepared for that, too. I know that I haven't a long time to live. All that I have said is the truth. When my time comes I hope that God understands me better for having told it. This is what matters.

On March 19, 1982 my father and I went to the Woodruff Library at Emory University to research the case again and learn more about the role of Alonzo Mann. This was the first time my father and I had gone together to research the case.

When we signed in, the librarian observed us curiously as we checked out more information.

She asked my father, "What did you think of little Mary Phagan?"

My father replied, "Young lady, I wasn't even a gleam in my father's eye in those years!"

We both laughed, and the librarian relaxed. When we told the librarian what we were looking for, she directed us to a copy of the Tennessean, since one of the Tennessean's reporters had been instrumental in breaking the story of Alonzo Mann's confession.

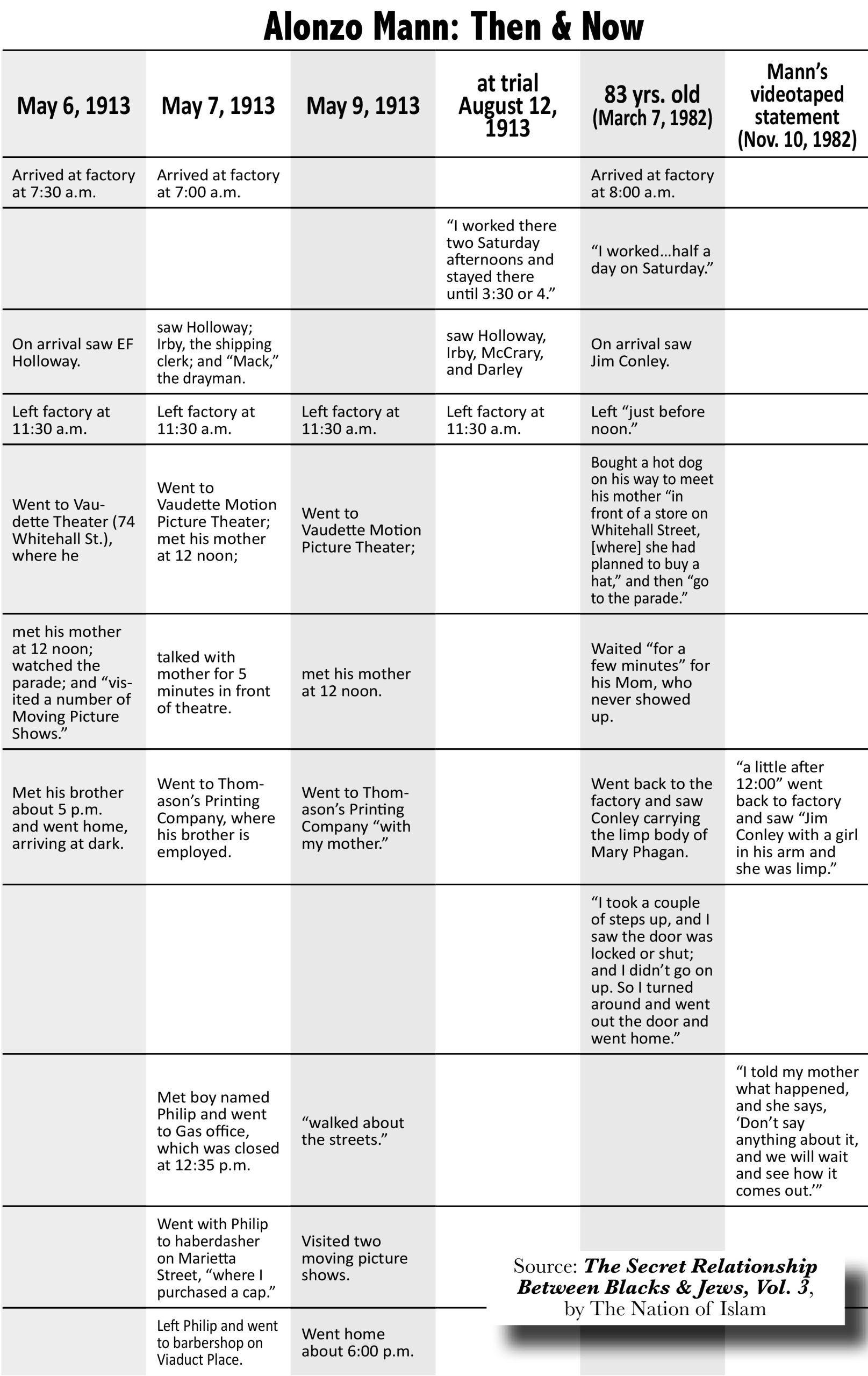

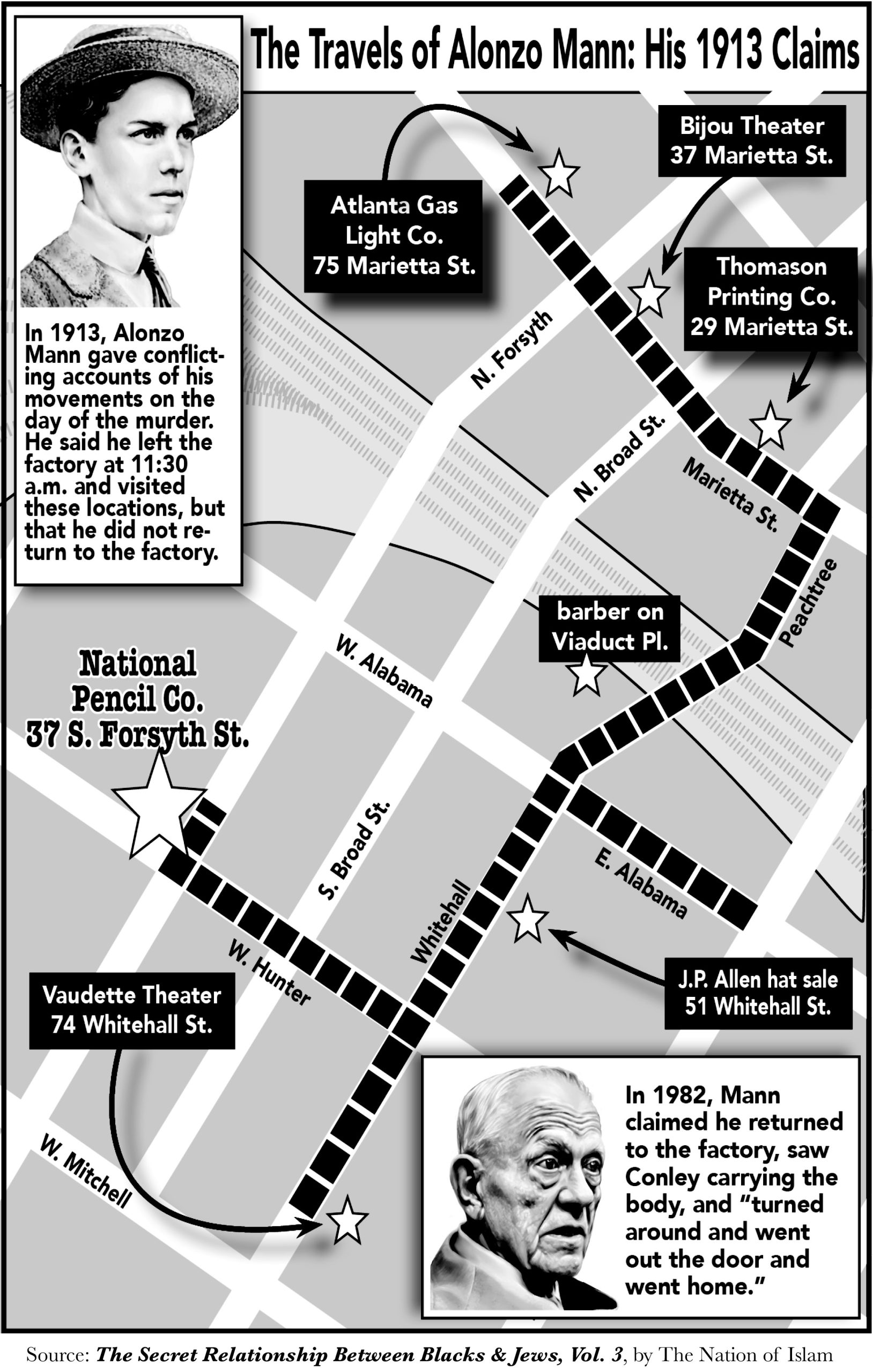

From our research, we learned that Alonzo Mann was indeed Leo Frank's office boy. Mann had begun working April 1, 1913, and had worked two Saturdays before the murder occurred. And he testified that he had left the factory "at half past eleven." Before we left that day, the librarian gave us the name and address of the Tennessean librarian.

On March 23, 1982, I wrote a letter to Sandra Roberts, the Tennessean librarian:

Your name was given to me by the librarian at the Woodruff Library at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. My father and I were researching the Mary Phagan/Leo Frank case. She showed us a copy of the Tennessean. We would like two copies if possible.

My father and I are very interested in this case because we are direct descendants of little Mary Phagan. My grandfather, William Joshua Phagan, was Mary's brother. My father is a nephew and I am a great-niece.

We would pay for the cost of the newspaper.

On March 26 Sandra Roberts called. She told me that the newspaper staff would be in Atlanta on March 31. She asked if they might drop by and hand deliver the newspapers.

Before this time, my father was always the one who dealt with anyone inquiring about the Phagans. He had always represented our family's opinion.

I called my father to let him know about the meeting and to see if he could be there to meet the staff, too. I had never spoken any of my feelings about the murder, and I could sense his concern. He didn't think he'd be able to be there, but he wanted to make sure that either a friend, my husband, or another family member would be.

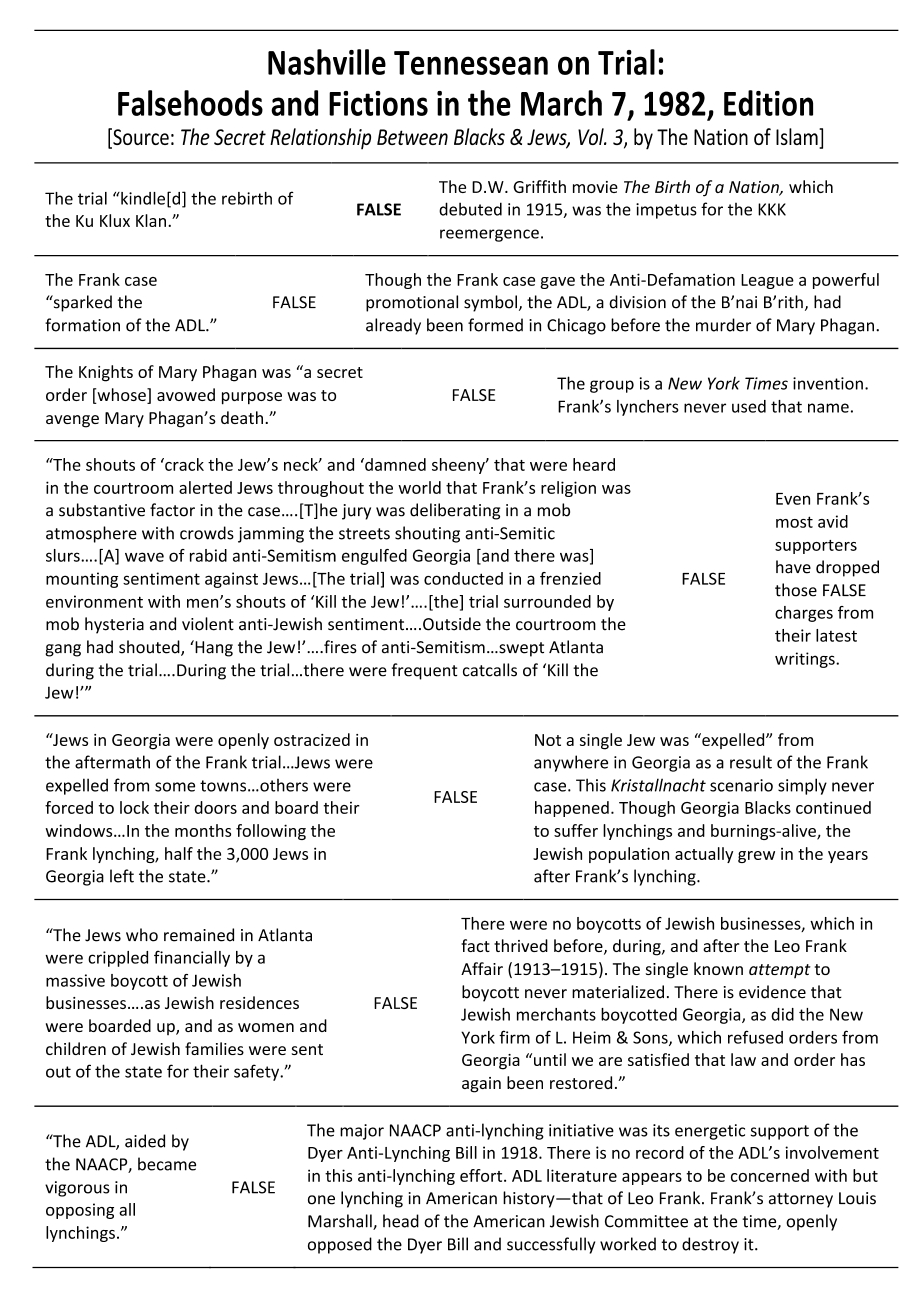

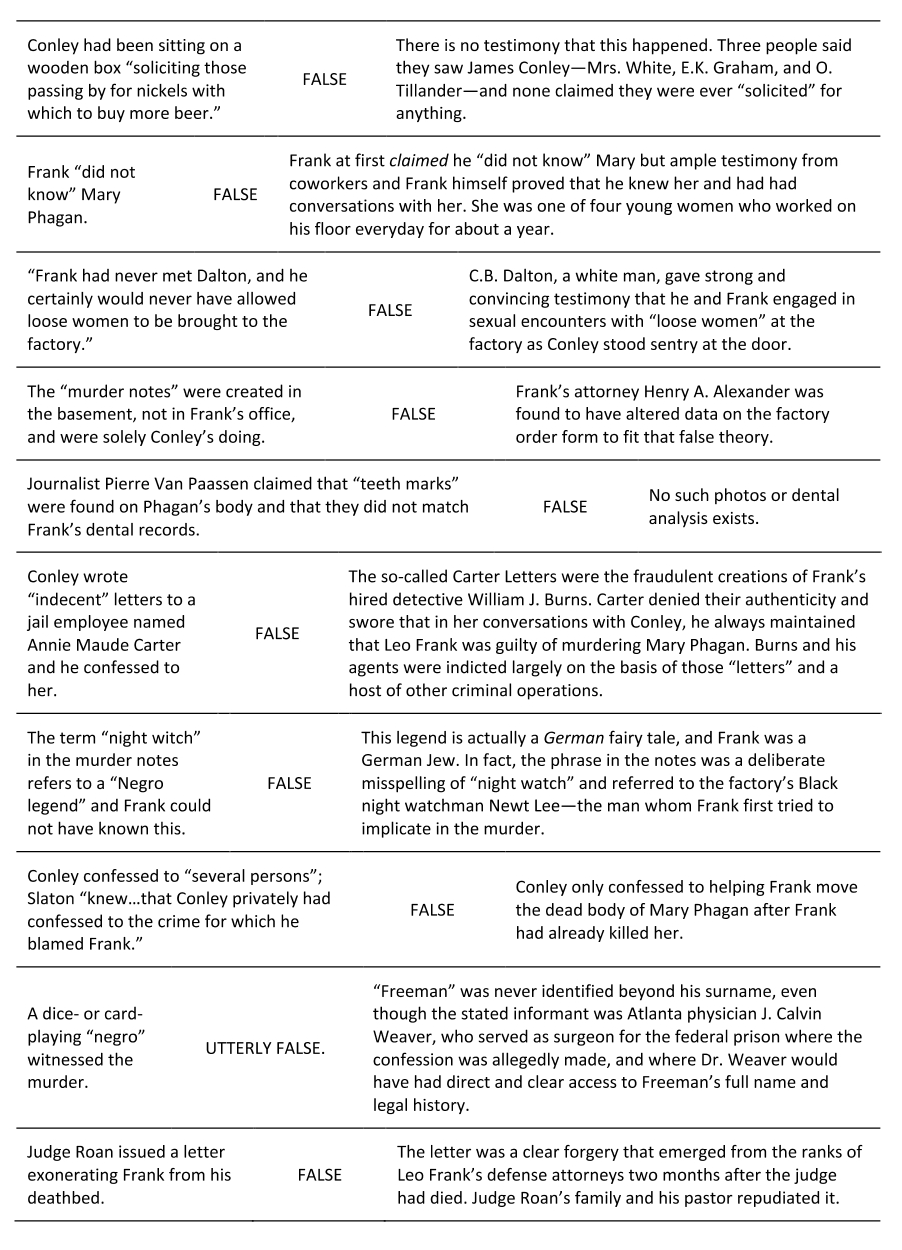

Nashville Tennessean changes the narrative of the original newspaper account to promote that "Mobs" were present during the trial of Leo Frank and to promote Anit-Semitism

Alonzo Mann's Movements and Alonzo Mann: Then and Now: 1913, 1982

Page 9, Pinkerton Report: Frank Case

Asst. Supt. H.S. reports:

Atlanta, Ga., Tuesday, May 6, 1913

On our arrival at the factory we interviewed Alonzo Mann, the office boy who resides at #109 S Gordon St. He has been employed at the factory for only one month and stated that he arrived at the factory on Saturday, April 26th, at 7:30 A.M. and found Mr. Holloway inside of the factory; that he left the factory at 11:30 A.M. leaving Mr. Frank and Miss Hall, the stenographer inside of the office. After leaving the factory, he went to the Vaudette Motion Picture Theater, where he met his mother at 12:00 noon and during the afternoon he watched the Memorial Day Parade and visited a number of Moving Picture Shows, and met his brother about 5:00 P.M. and went to his home, arriving there at about dark.

Page 14, Pinkerton Report: Frank Case

Statement of Alonzo Mann, of Atlanta, Ga.,

Made to F.C.P., of Atlanta, Ga., at the

National Pencil Company, Atlanta, Ga,

on Wednesday May 7th 1913.

I then went direct to the National Pencil Company factory, where I arrive[d] at about 7:00 A.M. The front door was open and I went upstairs to the office. I do not remember who was in the office when I entered same. However, soon after my [arrival] there, I saw Mr. Holliway, Mr. Irby, and “Mack”, the drayman, who took some rubbers and an umbrella that belonged to Mr. Schiff and left. Mr.

Hollaway and Mr. Irby remained in the office for about thirty minutes, perhaps longer, and we all three talked. Later on, I believe it was about 8:10 AM, Mr. Leo M. Frank came in. I do not think that Messrs. Holliway and Irby were there when Mr. Frank arrived, however, I do not remember, but I am sure that they were not in the office proper, for when Mr. Frank entered, he spoke to me and remarked “There is

not any one here but you and me”, and I replied “No”. I do not remember what took place at the office after that. I do not remember who came in or went out. Sometime during the morning, Mr. Frank went out I supposed to Montag Brothers, but I do not know, and I cannot recall how long he was gone, but it did not seem to be long. I cannot say whether it was thirty minutes or one hour, - I do not remember. I know that he came back that morning before I left. I left the office at 11:30 AM, and went to the Vaudette Theatre on Whitehall St., where I was to meet my mother at twelve o’clock. I met my mother just at twelve o’clock noon, as she came out of the theatre, and then went to Thompsons’ Printing Company, on Marietta St., where my [brother] was employed. We remained about that place for about five or ten minutes and we then went down Marietta St. to Peachtree St., where I left her. I retraced my steps on Marietta St. on my way to the Gas office. At the Bijou Theatre, I met a boy by the name of Philip, whose last name I do not know, and he went with me to the Gas office, which we found was closed. This was at about 12:35 PM. On leaving the Gas office, Philip and I went to a haberdasher’s store on Marietta St., where I purchased a cap, remaining there for about five minutes. On leaving that place, Philip and I separated, and I went to a [nearby] barbershop, it being on Viaduct Place, and I had to wait some time before I could be served.

The Barber took some time in cutting my hair, and I was in the shop for about twenty-five or thirty minutes.

alonzo-mann-pardon-testimony-updated

The Troubling Testimony of Alonzo Mann in the Murder of Little Mary Phagan

OCT 22, 2019

With today’s centennial of the death by lynching of Leo Max Frank, public attention has been fixed once again on the remarkable dual murders of Mary Phagan and Leo Frank. As is fairly well-known at this point, 13-year-old Mary Phagan was murdered in the National Pencil Factory in Atlanta on April 26, 1913. Leo Frank, her boss and last person to admit seeing her alive, was convicted of the murder.

His appeals went up to the Supreme Court of the United States and his conviction upheld at every level. Frank’s appeals to the administrative agencies of the State of Georgia also brought no change. Only when Governor John Slaton, a law partner of the Frank defense team, commuted the sentence to life imprisonment was Frank’s life apparently spared. But the outrage felt in Georgia over the impropriety of the Governor pardoning a client of his own law firm on his last day in office (and widely suspected of being bribed) resulted in a band of leading Marietta men planning and executing a daring break-in at the State Prison in Milledgeville, abducting Frank and driving over the primitive dirt roads of Georgia all night to hang him in Marietta at sunrise the next day.

The astonishing murder of Leo Frank has tended to soften the public’s view of his guilt in the murder of Mary Phagan.

Was Frank guilty of the murder of Mary Phagan?

His own subsequent murder is not material in establishing his innocence in the matter. It represents what might be called the “Ox-Bow Incident” mentality. We so dislike vigilante justice that we have a tendency to give the benefit of the doubt to the victims of such lynchings. Even in a case like this where Frank’s guilt was upheld at every level of the appellate legal system, we recognize his subsequent murder as an assault on the entire legal system.

Francis X. Busch, a renowned trial attorney of a half century ago, pointed out one of the most powerful pieces of evidence against Leo Frank. “As has been argued in support of the jury’s verdict, that in the passage of nearly forty years since Frank’s brutal execution, not a single additional fact pointing to his innocence has come to light.”1 Busch went on to worry if Frank may have been the victim of “one of the most flagrant miscarriages of justice in American criminal annals.”

The Phagan family conducted a full and complete interview in 1934 with Jim Conley, the star witness of the State against Leo Frank. Conley was also the man the Frank defenders settled on as the most likely murderer instead of Leo Frank. The Phagan relatives’ interview with Conley convinced them that Conley was telling the truth about Mary’s murder. Mary Phagan Kean wrote “[t]here is no way my father would have let Jim Conley live if he believed that he had murdered little Mary.”2

Thus it came as something of a shock to the general public that in 1982 newspaper attention suddenly focused on the elderly Alonzo Mann. Mr. Mann was about the same age as Mary Phagan at the time of her death and had testified as a defense witness for Frank in his capacity as Frank’s office boy at the murder trial. Now Mann emerged from the shadows with the startling revelation that he had actually seen Conley carrying the apparently lifeless body of Mary Phagan down the front staircase when he re-entered the Pencil Factory on April 26, 1913. Jerry Thompson,3Nashville Tennessean veteran reporter and anti-Klan investigator, worked up Mann’s story and brought before the public.

Mann was given lie detector tests and passed them. “Lie detectors” are not admissible in court in Georgia — unless all parties agree. They are of limited effectiveness because pathological liars and the very best of con artists often pass while persons of a more nervous disposition fail — even when the latter are telling the truth.

The Georgia Courts have mocked “lie detector” tests as follows:

There is simply no “lie detector,” machine or human. The first recorded lie detector test was in ancient India where a suspect was required to enter a darkened room and touch the tail of a donkey. If the donkey brayed when his tail was touched the suspect was declared guilty, otherwise he was released. Modern science has substituted a metal electronic box for the donkey but the results remain just as haphazard and inconclusive.4

On the national level the United States Supreme Court ruled in 1998 in United States v. Scheffer,5 that courts could bar the admission of the results of polygraph examinations in all cases without violating an accused’s constitutional rights. The Court did so because it noted that there is no consensus in the scientific community on the reliability of the “lie detector.” In short, the highest court in the land holds the “lie detector” to be “junk science.”

Mann’s ability to pass such a questionable test at best implies that he either completely believed his story or was an excellent story teller.

The Nashville Tennessean article was a tremendous hit; it was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and picked up by newspapers all over the nation. On television and radio programs commentators gleefully announced that Mann’s testimony erased all doubts — baseless though they might have been — that Frank was actually innocent of the murder of Mary Phagan. As the Tennessean’s headline for the special supplement of March 7, 1982, shouted: “AN INNOCENT MAN WAS LYNCHED.” Books, docudramas and prizes for investigative journalism rained down on the heads of the crusading scribblers.6

Mann’s story was significant in that it directly contradicted Conley’s testimony of how Conley got the body of Mary Phagan to the basement of the factory after the killing. As the reader may recall, Conley was definitive in his testimony that he used the elevator to transport the corpse. The elevator had always interested the Frank partisans and Mann emerged as the last living witness to the case to discuss this exact issue.

The affidavit executed by Mann may be summarized as follows:

He was called as a witness for Frank, but he did not then reveal to any lawyer about his knowledge contained in the affidavit. Now, he was coming forward after the lapse of seventy years. “I want the public to understand that Leo Frank did not kill Mary Phagan.” He blamed his parents, his speech impediment and his fear of the crowds outside the trial “yelling things like ‘Kill the Jew!’” for his reluctance to speak up. Mann stated he was too young at the tender age of 14 to have realized that if he told what he saw that Frank would have been found innocent.

Here is what Mann claimed he saw the day Mary Phagan died. When Mann arrived at the factory at 8:00 a.m, Conley was seated under the stairwell of the first floor of the Pencil Factory. Conley had already consumed a lot of beer. Mann ignored Conley’s request for money and went up the stairway to assume his duties as Frank’s office boy. Frank arrived shortly afterward. Mann worked till before noon when Frank permitted him to leave to join his mother for the Confederate Memorial Day parade. Mann promised Frank he would return after the parade and Frank allowed that he would probably still be at the Pencil Factory.

Leaving shortly before noon, Mann had not seen Mary Phagan come to collect her pay. Conley was still lounging in the stairwell when Mann left the factory. Mann did not pinpoint his departure time. He states he could have left between 11:30 or 11:45.

He stated, “[I]t could not have been more [emphasis added] than a half-hour before I got back to the pencil factory.” In other words, Mann returned somewhere between 12:00 and 12:15 based on his statement. Mann entered by the front door again, and looking to his right, saw Conley with Mary Phagan’s limp body (although he didn’t know Mary’s name at the time) standing between a trap door that led to the basement and the elevator shaft. He observed no blood or wound on the body of this limp, short white girl dressed in “pretty, clean clothes.” Mann was of the impression that Conley was about to dump the body down the trapdoor. He could not recall if the elevator was on the first floor; if it was not, then the shaft would have been open as well. “…[I]n a voice that was low but threatening and frightening to me he [Conley] said: ‘If you ever mention this I’ll kill you.’”

Mann started up the stairs to the second floor. He thought he heard movements up there, but thought better of it, turned and fled out the front door. Conley reached out for him, but Mann “raced away from the building.” Arriving at home, he told his mother — whom he was to have met at the parade — what he had seen. She immediately advised him never to tell a soul. “She told me that I was never, never to tell anybody else what I had seen that day at the factory. She said that she didn’t want me involved, or the family involved, in any way. She told me to go on about my business as if nothing had happened and that sometime soon I would have to quit working there. From then on, whenever I was at work, I steered clear of Jim Conley. I kept away from him and he did the same.”

“When my father came home my mother explained to him what I had seen and what Conley had said to me. My father told me to forget it and never mention it.”

Later, when questioned by detectives, Mann never told them about his return to the Pencil Factory building. At Leo Frank’s trial, while testifying as a witness for Frank, Mann only answered the questions he was asked. He, following the advice of his mother and father, did not volunteer any further information. Mann offered his opinion that Conley was after Mary’s pay; he was not planning a sexual assault.

“Many times I have thought since all this occurred almost seventy years ago that if I had hollered or yelled for help when I ran into Conley with the girl in his arms that day I might have saved her life. I might have. On the other hand, I might have lost my own life. If I had told what I saw that day I might saved Leo Frank’s life. I didn’t realize it at the time. I was too young to understand.”

Family members continued to tell Mann not to tell anyone his story for years afterwards. An Atlanta newspaperman unnamed by Mann (but said by others to have been Ralph McGill, another crusading, Pulitzer Prize-winning liberal journalist) was disinterested in his story.

Mann also contradicted the testimony of the female factory employees who accused Frank of bringing women into the factory for immoral purposes. Mann never witnessed any such conduct.7 (Mann did not mention that he began working for Frank on April 1, 1913 so he had only been at the factory for twenty-six days at the time of murder.)

The Mann affidavit reopened the drive of the Jewish community for a “posthumous pardon” for Leo Frank. At a press conference at the Atlanta Jewish Community Center on April 1, 1982, the drumbeat began again. Jerry Thompson, at the press conference, was asked about the Phagan family’s reactions to all this information. “Jerry Thompson stated that some Phagan family members upheld their belief in the convicted Leo Frank’s guilt while others ‘were trying to be objective.’”8 “Sherry Frank (no relation to Leo Frank), area director of the American Jewish Committee, said Jewish leaders would like to make a possible exoneration of Frank an issue in the gubernatorial race this year.”9

Alonzo Mann, possibly because of his age and infirm heart, refused to respond to any questions except through his handlers at the Nashville Tennessean. This author contacted the Tennessean and was so informed at the time the news broke. Mary Phagan Kean was given the same answer, but because of her family connections she was finally able to meet Mr. Mann and form some impressions about him. She thought him “a fine gentleman; he believed what he had seen to be evidence of the truth.”10

Since Mann was never subjected to any cross-examination nor, evidently, even tough questioning about these matters, we are left with three possibilities concerning the worth of his testimony on an historical basis. It has long been held in Anglo-Saxon law that trial by affidavit is worthless and the cross-examination of a witness is essential to establish the truth or falsity of a proposition. So while Alonzo Mann’s affidavit is valueless from a legal standpoint, it does have historical significance and must be so analyzed as we find it.

Mann’s recollections could be (1) completely accurate and factual; or (2) weakened by seventy years of guilt and blurred memories, but basically accurate; or (3) a complete fabrication drawn up either by himself or with the assistance of other parties for a number of plausible reasons.11

Since Mann cannot be examined, having answered to the highest tribunal on March 19, 1985, let us look more closely at the statement itself.

First of all, Mann states that mobs were shouting things like “Kill the Jew” outside the trial. The most careful writers on the subject all agree that this is an urban myth with no basis in fact. Steve Oney, the most recent author on the subject, points out that there is no contemporary evidence for such a statement.12 Governor Slaton in his commutation order denied that Frank had been tried by a mob. But, like the typical urban myth, the legend persists. It is probably propelled by later events after the Slaton commutation and the assault of the “Knights of Mary Phagan” on the State Prison in Milledgeville.

In the statement, Mann put himself as leaving the factory between 11:30 and 11:45. In his trial testimony, as recorded in the brief of evidence, Mann testified twice that he departed at 11:30.13 Since his testimony was given closer in time to the event in issue, we may presume that at least he was inaccurate in the later affidavit as to the time of his departure unless he was fudging on that topic when testifying for Frank at trial. So Mann’s affidavit is clearly at variance in this important matter with his own trial testimony given relatively shortly after the event. Given the heavy emphasis the defense attached to the timing of the assault on Mary, this is significant to say the least. It would seem highly unlikely that the skilled interrogation by Frank’s attorneys failed to unearth the later departure time (to say nothing of Mann’s return to the factory) given their theory of the case turned on the time element so heavily.

It is also noteworthy because of the importance attached to the timing of the arrival of Mary at the Pencil Factory. The defense made much of the testimony of streetcar operators that Mary could not have possibly arrived at the factory prior to 12:12 p.m. Although Dorsey seriously damaged this theory in his cross-examination, the defense steadfastly held to this narrative. If Mann’s recollections are correct, then pressing his affidavit times to the furthest, most favorable limit for Frank, the latest Mann could arrive back at the factory on the fatal day is 12:15 p.m. Under Mann’s time constraints, Mary had to be able to ascend the staircase, obtain her pay envelope from Frank, ask about work on Monday and descend the staircase, be attacked by Conley either upstairs or downstairs (without Frank hearing any struggle or screams in the otherwise quiet factory, as it was a holiday) be lifted up and carried by Conley to the point where he was seen by Mann next to the “hole” and elevator shaft. All this had to occur within an absolute maximum of three minutes. If Mann’s statement that he was away from the factory for not more than one-half hour is true, then in order to get Mary to the factory after Monteen Stover testified she arrived, Mann’s departure time had to change.

Stover’s unimpeached testimony is that she was in Frank’s outer office from 12:05 until 12:10 by the clock on the wall in the office. Frank was absent from his office and not a sound was heard by Stover. Consequently, the defense always asserted that Mary arrived two minutes after Monteen left — just enough time for the two of them to miss each other on the staircase and the street outside the factory. If Mann was gone for no more than thirty minutes, then his departure time must be shifted forward from his trial testimony or else he returns before Mary, by Frank’s testimony and the elaborate defense calculations, could have even arrived at the factory. No Frank defender has offered any explanation for the new time problems created for the defense by Mann’s affidavit.

Consider the plausibility of the affidavit statements concerning the response of Mann’s parents to the news that their son had witnessed what was doubtless the most sensational murder of their lifetimes. Conley returned to work on Monday, April 28th after the murder. Mann evidently returned to work as well according to his affidavit. Conley would continue to report to work until his arrest on May 1.

Can we believe that a fourteen-year-old lad would report to work alongside a black man who he had every reason to believe had committed the murder of Mary Phagan? Mann would have permitted an innocent man, the black night watchman Newt Lee, to languish in the jail while the sweeper Jim Conley, whom he feared — now with better reason than ever before — looked malignantly at him each day. Is that believable — even in present day America?

Gentle reader, life in 1913 Atlanta was considerably rougher. Keep in mind what Mann asked us to believe. Once he eluded Conley’s outstretched hand, he was on the sidewalk outside the factory. The streets of Atlanta were teeming with crowds attending the Confederate Memorial Day parade. If he raised his voice to call for help, a crowd would have quickly responded. The life expectancy for Mr. Jim Conley would have been very short if a crowd of 1913 whites found a black man holding the limp (and possibly dead) body of an adolescent white girl in that time and in that place. Yet Mann didn’t know what to do; he didn’t alert any policeman he may have chanced to meet nor the trolley crewmen on his way home. He didn’t speak to anyone till he got home. He raced straight home where his missing mother had already arrived. His parents, certainly not made of stern stuff, advised silence. Even after Frank was arrested the Mann clan remained mum.

The most amazing part of the affidavit is Mann’s statement that his loving parents, worried about the family getting involved in all this, still advised him to return to work where he would be in close proximity to the purported murderer, Jim Conley. Did it never occur to any of them that Conley could just as easily silenced the only witness to see him with the girl’s body? Why advise their beloved son to return to the zone of danger and yet remain silent?

But suppose all of this was true. The Manns thought Conley so dangerous to Alonzo’s safety that they remained silent and let their son go back to work with a homicidal maniac. Once Conley was in police custody that problem was resolved. What was more, a reward was offered for evidence leading to the conviction of the murderer. Did the Manns have no interest in talking about a murderer now in police custody with the additional attraction of a cash reward?

Conley is thought to have died about 1962. Why didn’t Mann come forward then? Surely he didn’t fear the powers of Conley to do him harm extended beyond the grave.

Finally, we come to Conley, “the Prince of Darktown.” To listen to the Frank defenders recite their narrative, Conley was a criminal mastermind who was able to outwit and frame poor Leo Frank and thereafter to withstand the pounding and intense cross-examination of the finest criminal defense attorneys in Georgia of their day. All the time, the criminal mastermind was well-aware that a white boy of fourteen had seen him with the body! Under these circumstances, would Conley have shown up at the National Pencil factory on the Monday after the murder insouciant and confident? Clearly, Conley appeared because he believed he was safe and protected from whatever role he had in this homicide. If Mann saw him on the first-floor landing and Conley knew it, why would he loiter at the plant until he was arrested on May 1, 1913? Reason and experience with criminal defendants dictates that had the incident occurred as Mann related, Conley would have caught the first freight train headed out of Atlanta and “rode the rods” to any distant geographical point to escape the accusing finger of Mann and the pursuing lynch mob. If Conley did choose to remain in town, wouldn’t he have taken more effective steps to silence a witness than simply warning Mann to shut up?

Furthermore, why would the Moriarty criminal mastermind of Conley not incorporate the Mann incident into his statement and confession to the police? If Conley’s confession was concocted, why would he go to the trouble of inventing the tale of the elevator knowing that Mann stood able to give him the lie? He could have even used Mann to bolster his story by claiming that he carried Mary’s body down the steps at Frank’s direction and dropped it down the trapdoor. Furthermore, Mann could verify that story! “Bring in the office boy and question him!” Conley could have challenged Mann and turned an uncertainty into supporting evidence.

Conley, though, stuck to his version of how the body was transported to the elevator and never volunteered that Mann was a possible witness.

Conley was bringing Mary down the stairs. Where had they been? Why had Frank heard nothing if the assault took place virtually in his office? Additionally, the condition of Mary Phagan’s body when found was quite different than described by Mann. This can only be accurate if Mary was unconscious and then revived when Conley got her to the basement. When Mary’s body was found it was filthy, her dress was torn and she was so blackened by soot and dirt that some of the police could not tell what race she was. (Which could lead to a third explanation for her death. That explanation, unexamined by all the Frank apologists, is that Frank assaulted Mary in the metal room. She was knocked against a machine and fell unconscious. Frank thought her dead and summoned Conley. Conley then finished the job after she came to in the basement. Before dying, Mary apparently put up a real struggle. This explains some of the irregularities in both Frank’s and Conley’s stories. But the preference is to depict Frank as a martyr, a real mensch. This alternative doesn’t please the Frank community. Frank would still be a murderer under the law of almost every state in the union and in 1913 would have gotten the death penalty.)

One member of the Pardons and Parole Board considering Mann’s affidavit pointed out that Mann dropped out of school to work against his parents’ wishes. “Why would a man who wouldn’t obey his parents about school,” [Michael] Wing wondered, “obey them when it came to potentially letting an innocent man hang?”14

Furthermore, Mann showed no concern that day about Leo Frank, a man for whom he expressed respect in later years. Frank, after all, should have still been in the building when Mann returned to find Conley toting a dead girl in his arms. Mann stated he thought he heard movement upstairs. He evidently never considered the fact that Frank — whom he believed to be in his office upstairs — or anyone else still in the factory could have been in peril even decades later when reviewing the case.

And we have the issue of the defense attorneys and police investigators. Evidently, none of them were able to pierce the veil Mann and his family cast about his covert knowledge. This young lad was able to fool even trained investigators who were desperately trying to either free their client or uncover the real story. The defense attorneys interviewed him and decided to use Mann as a witness for Leo Frank. Nevertheless, this naive lad of 14, who had no idea that his information could save an innocent man’s life and who quaked in terror of the now incarcerated Conley, never gave his secret away.

Given the huge problems with the 1982 Mann statement on its face, it is impossible to believe that Mann told the truth in that document. All human experience runs directly contrary to the behavior he attributes to almost every participant in his affidavit.

The Phagan case was cursed from the very beginning with people volunteering “tips” and “clues.” It appears most likely that Alonzo Mann was merely the last of many to offer a fanciful solution to the case.

Since his solution was superficially suited to the Frank defenders’ longstanding press campaign to exonerate Frank, it has received fabulous coverage. Many articles and news statements flatly assert that it closes the case entirely.

As helpful as the Mann statement appeared to be at first blush to the Frank defenders, it does have a major defect; it merely disputes Conley’s testimony about how the body was transported to the place it was found. It does not establish whether Conley or Frank was the murderer.15 After all, Frank was still upstairs when Mann says Conley was carrying the body from that location. What was Frank doing upstairs when Mary Phagan was attacked?

Thus because of these shortcomings and infelicities in Mann’s statement, the document was not of sufficient gravitas or credibility outside of press newsrooms to create the expected popular groundswell which would impel the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles to issue a pardon or other exoneration of Frank from culpability in the murder of Mary Phagan.

But the shortcomings outlined above did not give serious pause to the Frank camp.

Because it disputed the Conley testimony, it was immediately ballyhooed, without close consideration, as a complete exoneration of the Leo Frank.

It does no such thing.

1 Busch, Francis X., Notable American Trials: Guilty or Not Guilty (London: Arco Publications, 1957), 74.

2 Phagan (Kean), Mary. The Murder of Little Mary Phagan (Far Hills, NJ: New Horizon Press, 1987), 28.

3 Thompson had worked as an informant infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan for the paper and afterwards became an ardent Frank advocate insofar as Leo Frank’s guilt in the Phagan murder was concerned.

4 State v. Chambers, 240 Ga. 76, 81, 239 S.E. 2d 324 (1977). While written in dissent, this language has been adopted by the Supreme Court in subsequent cases such as Carr v. State, 267 Ga. 701, 482 S.E. 2d 314 (1997). The author has had personal experience with “lie detectors” as well. He was unable to convince an examiner that while he had been a union member, he was not a labor organizer when required to take a test for employment. The job was denied. Georgia will admit lie detector tests if both sides agree, but the reader can envision the value of testimony that both sides see as helpful. Basically, the “lie detector” seeks to “bolster” the credibility of a witness. It is not admissible in most American courts. More recent concern about national security following the terrorist episodes of September 11, 2001 has further eroded the credibility of “lie detectors.” A CBS News, “Not Close Enough for Government Work,” report dated October 8, 2002, reported the National Research Council as stating “National security is too important to be left to such a blunt instrument.”

http://www.cbsnews.com/news/not-close-enough-for-government-work/

5 118 S.Ct. 1261 (1998)

https://www.dauberttracker.com/documents/authorities/Scheffer.pdf

6 Phagan, The Murder of Little Mary Phagan, 246

7 Ibid., 247–261.

8 Ibid., 262.

9 The East Cobb Neighbor of April 6, 1982 as quoted in Phagan, The Murder of Little Mary Phagan, 264–265. Indeed, it did become an issue. Candidate and eventual victor Joe Frank Harris stated he would pardon Frank — even though the governors of Georgia had no legal or constitutional authority to do so.

10 Phagan, The Murder of Little Mary Phagan, 311.

11 Neuroscience is pressing forward on the issue of memory function. Suggestibility in interrogation, memory distortion in the aging process and abuse of substances (such as alcohol) are all at issue in Mann’s recollections. Memories of traumatic events have been shown to change with time and it has been convincingly demonstrated that in some cases that physic phenomena in the nature of memories are often created for traumatic events that did not actually happen. These are all problems with honest witnesses, let alone witnesses that may have been influenced by a desire for fame, notoriety or mere lucre.

12 See Steve Oney, And the Dead Shall Rise (New York: Pantheon, 2003). An example would be at page 343. There were times when the audience would laugh or applaud, but the jury, when out of the courtroom, were not sure for whom the demonstrations were intended. In newspaper interviews and public appearances Oney flatly states there were no “Kill the Jew” chants.

13 Brief of Evidence contains the entire direct testimony of Alonzo Mann in 16 sentences, most of which deal with who was in the factory. The cross-examination was but three sentences dealing with the time Mr. Frank was out of the office.

Brief of the Evidence. In the Supreme Court of Georgia, Fall Term, 1913, Leo M. Frank, Plaintiff in Error vs. the State of Georgia, Defendant in Error, 123.

14 Clark J. Freshman, “By the Neck Until Dead: A Look Back At a 70 Year Search for Justice,” American Politics, January 1988, 31.

15 Logic would follow that disproving a critical part of Conley’s testimony does and should create doubt about other parts of his testimony: Falsum in unum, falsum in omnibus. But the same maxim applies to Mann’s statement — which was not exposed to days of grueling cross-examination by skilled attorneys.

By Mickey Lawson

- Chapter 20: 100 years: 2013 Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: January 14th, 2024]

- Chapter 21: 2015: 100 years after Leo Frank Lynching Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: January 15th, 2024]

- Chapter 14: 1989: ADL Attorney Dale Schwartz Revisionism of Judge Roan Statement to Jury Final st of Judge Roan's Charge to Jury Final [Last Updated On: July 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 16th, 2023]

- Chapter 16: 1998: Parade the Broadway musical is a corruption of history and radical attempt to whitewash a horrible murder and pin it on Jim Conley, a Negro Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: November 5th, 2023]

- Chapter 22: 2019: Fulton County Conviction Integrity Unit [CIU] Established to Exonerate Leo Frank Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: January 21st, 2024]

- Chapter 27: Cobb Librarian Discusses the Lynching of Leo Frank: 2023 Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: January 23rd, 2024]

- Afterward - Pardon: 1986 Final [Last Updated On: July 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Appendix [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2024]

- Introduction To Chapters [Last Updated On: April 22nd, 2025] [Originally Added On: April 22nd, 2025]

- Chapter 1 - "ARE YOU, BY ANY CHANCE...?" Final [Last Updated On: July 24th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 11 - The Phagans Break Their Vow Of Silence Final [Last Updated On: July 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 12 - Application For Pardon, 1983 Final [Last Updated On: July 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2023]

- Chapter 2 - The Legacy Final [Last Updated On: August 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 3 - My Search Begins Final [Last Updated On: July 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 4 - The Case for the Prosecution Final [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 5 - The Case For The Defense Final [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 6 - Sentencing And Aftermath Final [Last Updated On: October 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 7 - The Commutation Final [Last Updated On: July 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 8 - The Lynching Final [Last Updated On: October 10th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 9 - Reverberations Final [Last Updated On: July 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Contents: Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2024]

- Dramatis Personae/Who's Who: Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2024]

- Epilogue: Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2024]

- Chapter 23: Fulton County Paul Howard defeated by Fani Willis; November 6, 2019 Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2024]

- Glossary: Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2024]

- Index: Final [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: January 1st, 2024]

- INTRODUCTION: FINAL [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: December 18th, 2023]

- Chapter 28: January: 2024-2025 Fani Willis, Fulton County DA Investigated by Georgia Senate Commission Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: January 23rd, 2024]

- Chapter 25: Jonathan Greenblatt: August 17, 2023, 2022, 2021 Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: January 14th, 2024]

- Chapter 18: Leo Frank Historical Marker Approved in 2006; Dedicated 2008 Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: January 4th, 2024]

- Chapter 26: Phagan Family Position Paper 2021 Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: January 14th, 2024]

- Preface: Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: October 16th, 2023]

- Chapter 24: Roy Barnes Mercer Law School (November 12, 2019) Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2024]

- Chapter 29: Seeking Justice for Little Mary Phagan: Add Newsletters 2-14 Here Phagan Family Newsletter Collection [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: July 23rd, 2024]

- Chapter 19: PBS Documentary: The People vs Leo Frank: 2008; Seeking Justice The Leo Frank Case Revisited: 2009 Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: January 8th, 2024]

- Selected Bibliography: Final [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 25th, 2023]

- Chapter 17: 2003: Steve Oney Publishes Book Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: November 5th, 2023]

- Chapter 13: 1987-1988 Mary Phagan NBC "Docudrama" Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: October 20th, 2023]

- Chapter 15: 1995: The secret deceitful underhanded revisionist political Marker Change at Mary Phagan's Grave by the Parks and Tourism Committee, Marietta City Council and the Jewish Community. Final [Last Updated On: April 20th, 2025] [Originally Added On: October 16th, 2023]